Most of us are aware that forage losses can accumulate in a hurry, particularly for hay. Adding up potential losses incurred during harvest, storage, and feeding, as much as 60% of forage dry matter can be lost between the field and the cow’s mouth.

Whether you purchase hay or make it yourself, that hay is an investment, so why not do your best to preserve that investment? A huge amount of money is lost each year on dry matter and forage quality losses that occur while hay is stored. Consider the fact that the outer six inches of a round bale account for about one-third of the bale’s total dry matter—this means a few inches of deterioration can add up to a lot of loss! Many of us probably do not realize how large our losses really are, but round bales can lose anywhere from 5 to 40% dry matter in as little as six months depending on the climate and the degree of protection from the weather.

Hay dry matter losses have a simple explanation—moisture. At some point, water entered the bale and was not able to leave through evaporation, resulting in spoilage. The deeper that water penetrates the bale and the longer that water stays in the bale, the greater the expected losses. Fortunately, there are several management practices that have been proven to be effective at reducing hay losses during storage.

“Bales stored outside will readily wick up moisture from the ground, so storing them in a well-drained area or even up off the ground (if possible) is ideal.“

Focal point

|

Indoor Storage

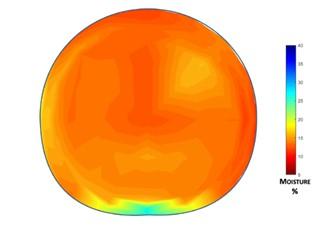

While this option is not always feasible, indoor storage remains the best way to keep hay losses to a minimum. Although bales stored indoors can still be subject to some loss, those losses will generally be minimal and bales will conserve their value very well. The images below (Figures 1-5) come from a study conducted at South Dakota State University evaluating the impact of different hay storage options on bale moisture content. For each image, areas shaded in blue represent regions of higher moisture, where spoilage will be likely, while a yellow or red color represents areas with less moisture where spoilage is not likely to occur. This first image is depicting moisture distribution for a hay bale stored indoors—in this case in an open front hay shed. Although the bottom of the bale wicked some moisture up from the dirt floor, the vast majority of the bale contained less than 20% moisture (Figure 1).

Although it has been documented that indoor storage of round bales typically results in the best economic return, the reality is indoor storage is not always feasible and many round bales will continue to be stored outside. Fortunately, there are still things we can do to limit forage losses when round bales are stored outdoors.

Outdoor Storage

When storing bales outdoors, the overarching goal is to limit places where moisture will collect and maximize air movement and sunlight so bales are able to dry out more easily after precipitation. Bales stored outside will readily wick up moisture from the ground, so storing them in a well-drained area or even up off the ground (if possible) is ideal.

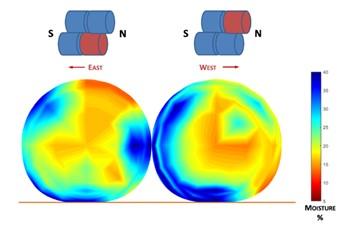

When storing bales outdoors in rows, the common recommendation is to leave several feet of space between rows to allow for more airflow and keep the bottom quarter of the bales drier. If this space is not left between the rows and instead the bales are butted up side-to-side, water runs down into the crevice formed by the touching bales and results in a very high moisture levels and an increased chance for spoilage where the bales touch (Figure 2).

It is fairly common practice to store hay as a row of bales butted tightly together end-to-end. However, no matter how tightly those bales are pushed together, it is still possible for water to drain and collect between the vertical faces of the bales. Consequently, it is more difficult for these bales to dry and researchers found that about 66% of the bale was above 22% moisture when hay was stored end-to-end (Figure 3).

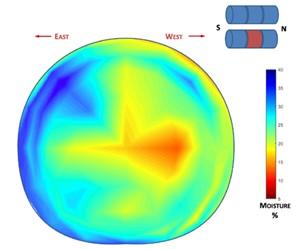

When bales were left outside with no contact (a gap was left both between the bales in a row and between the rows), air movement was not restricted by any neighboring bales and only about 15% of the bale was above 22% moisture (Figure 4). This suggests that spoilage can be limited when the bales are not in contact with each other and indicates there might be some value in leaving a space between bales in a row.

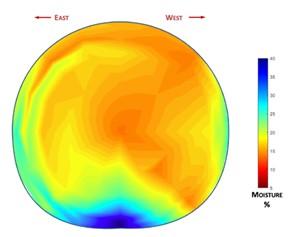

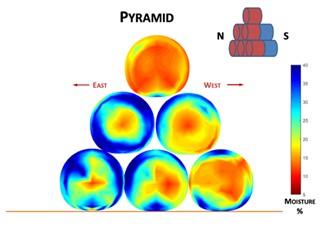

It is also fairly common practice to stack bales to reduce the amount of space needed for storage. However, unless the stacked bales are covered, water that is shed from the upper bales will flow down to the bales below and can collect in all of the crevices formed by the touching bales. Since the bales on the bottom of the stack have limited air movement and exposure to the sun, the water cannot be readily evaporated, leading to increased moisture levels and an increased chance for spoilage (Figure 5). Bales on the bottom of the stack can also lose some of their integrity and start to squat, which means additional contact with the ground, increased moisture accumulation, and greater spoilage potential.

In addition to the considerations mentioned above, other strategies you can use to limit forage losses include:

- Utilize net wrap—net wrap is far more effective than twine and will reduce losses by shedding water better. Research has shown that dry matter losses for net-wrapped bales will be reduced by about one-third compared to twine-wrapped bales.

- Make dense bales—a loose bale lets water and air in, while a denser bale will shed water better. A dense bale will also sag less, so there is reduced bale-to-ground contact, which is important since much of the storage loss occurs on the bottom of the bale.

- Keep bales off the ground—having something like a rock base under round bales is ideal to promote drainage, but if that is not practical then select an area that is well-drained and/or use something like wooden pallets or used tires to keep bales up off the ground.

- Keep bales out of the shade—place bales where they are not shaded by buildings or trees to maximize sun exposure and drying.

- Leave space between rows—leave at least 3 feet of space between bale rows to enhance air movement and allow the lower quarter of the bale to dry.

- Stack only if covered—unless you are fully covering the bales don’t stack bales in a pyramid or other formation where the sides of bales will be touching, as this allows water to collect in the crevices between bales.

These best management practices for storing round bales have been proven to be effective, so be sure to protect your investment and limit your losses by storing forage properly.

This article appears on October 4, 2022, in Volume 3, Issue 3 of the Maryland Milk Moos newsletter.

Maryland Milk Moo's, October 4, 2022, Vol.3, Issue 3

Maryland Milk Moos is a quarterly newsletter published by the University of Maryland Extension that focuses on dairy topics related to Nutrition and Production, Herd Management, and Forage Production. To subscribe to this newsletter, click the button below to enter your contact information.