FS-2024-0736 | August 2025

Spring-Seeded Cereal Cover Crops for Weed Management in Plasticulture Cucurbit Production

By Kurt Vollmer, Dwayne Joseph, Alan Leslie, Cerruti Hooks, and Thierry Besançon

Plasticulture Vegetable Production

Plasticulture is a method for growing vegetables using plastic mulch to achieve higher yields and better-quality produce. Plastic mulch is generally applied to raised beds containing drip irrigation. Raised beds and plastic mulch warm the soil, reduce water loss and weed pressure under the plastic, and protect plants from diseases, while drip irrigation provides a uniform supply of water and nutrients. However, plasticulture results in wider row spacing between plastic mulch rows (6 to 8 ft.), which leaves extra spacing for weeds to grow, often reducing yield and making harvest more difficult.

Common Weed Control Practices

Growers often apply the following practices to control weeds in plasticulture.

a. Mechanical Weed Control

Mechanical practices to control weeds in the inter-row (between plastic mulch) areas include cultivation, mowing, and hand weeding. Cultivation controls weed seedlings that emerge early in the season, but success depends on the timing of the operation. Frequent cultivation is often needed to manage the diversity of weed species that emerge from the inter-row area, and this practice can damage plastic mulch, when attempting to control weeds adjacent to the plastic edge. The need to avoid contacting the plastic with cultivators may allow weeds to escape. Consequently, close mowing can have similar drawbacks to cultivation and may not control low growing weeds. Hand weeding can be Systemslaborious and cost-prohibitive, as multiple weedings may be required during the growing season.

b. Chemical Weed Control

Soil-applied herbicides can be directed to row-middles prior to laying the plastic or transplanting the crops. These herbicides provide 3 to 6 weeks of residual control before postemergence weed control tactics are needed. Postemergence herbicides can be applied to control weeds that have already emerged. These benefits notwithstanding, there are several challenges to using herbicides in plasticulture vegetable production.

- Soil-applied herbicides are designed to keep seeds from germinating or sprouting, but will not control weeds after they emerge.

- The majority of postemergence herbicides cannot be broadcast over the crop, and must be applied as directed applications to row middles.

- Weeds may not be controlled by certain herbicides due to:

- residual herbicides not being activated due to less than adequate irrigation/rainfall,

- a natural tolerance to certain herbicides, or

- an evolved resistance to herbicides that were previously effective.

In both cases, weeds that are not effectively controlled with herbicide applications will continue to grow, compete with crops for resources, and interfere with harvest and other field operations.

c. Cover Crops

Cover crops are crops that are not grown for profit. Rather, they are planted to prevent soil erosion, improve soil health and quality, and suppress weeds. Cover crops can provide these benefits as either living or dead plant material. Actively growing cover crops (living mulches) compete with weeds for all resources required for growth and development such as space, sunlight, water, and nutrients (Cornelius and Bradley 2017, Vollmer et al. 2020, Hirsh et al. 2025). Dead cover crops (cover crop residue) provide a layer of natural mulch that helps prevent weed emergence.

Integrating spring-seeded cover crops with herbicide treatments for in-season weed control

Herbicide-resistant weeds such as Palmer amaranth, smooth pigweed, and redroot pigweed can be difficult to manage with herbicide applications. Populations of all three species have developed resistance to Group 2 (ALS-inhibiting) herbicides such as Sandea® (halosulfuron), which are commonly used to control broadleaf weeds. When using spring-seeded cover crops it is important to establish the cover crop before weeds start to emerge. This involves forming the beds and laying the plastic in early spring (mid- to late April), followed immediately by cover crop seeding. This is contrary to most cover cropping systems, where cover crops are fall-planted and have months to establish themselves (Hirsh 2024). Laying plastic mulch is rarely compatible with existing fall-planted cover crops, as the presence of cover crop residue can result in uneven bed formation. Seeding a cereal rye or oat cover crop between the beds immediately after laying plastic in the spring can offer similar weed control benefits as fall seeded cover crops and preemergence herbicides (Figure 1).

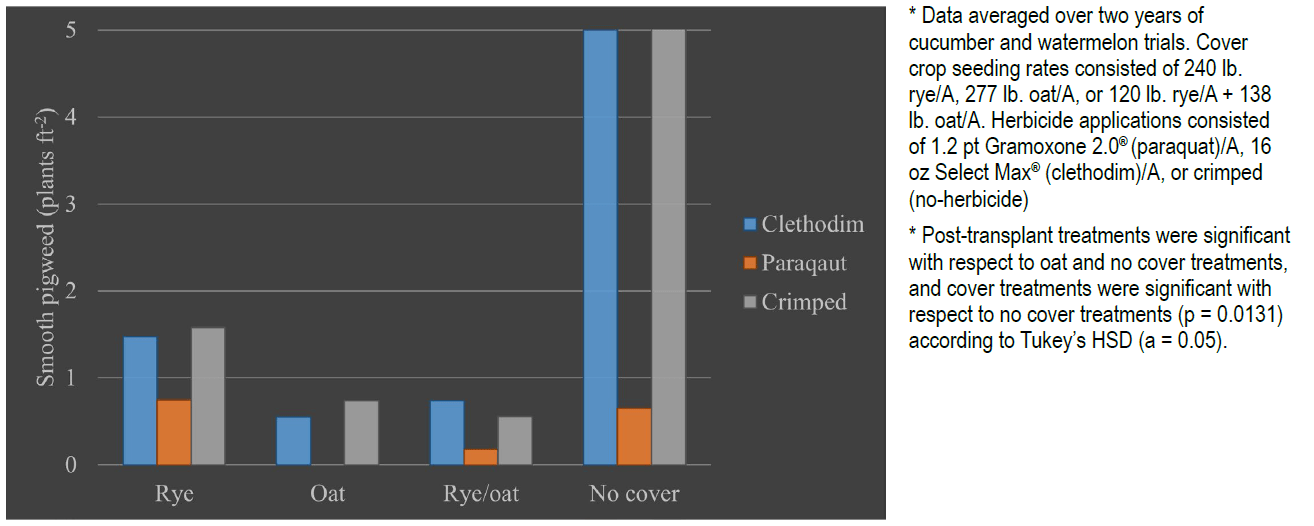

Actively growing oat and rye cover crops can reduce the density of species such as smooth pigweed by as much as 76%, early in the growing season. When weeds are shorter and density is low, this makes them optimal targets for contact herbicides such as paraquat (Gramoxone®) as optimal spray coverage can be achieved. Applying these herbicides at the right stage cover crop growth stage (jointing to heading) can serve to both control emerged weeds and terminate the standing cover crop (Figure 2). Afterwards, the decaying cover crop residue can provide a thick layer of mulch (3,997 to 5,138 lb. biomass/A) to inhibit additional weed emergence until the residue breaks down (Figure 3).

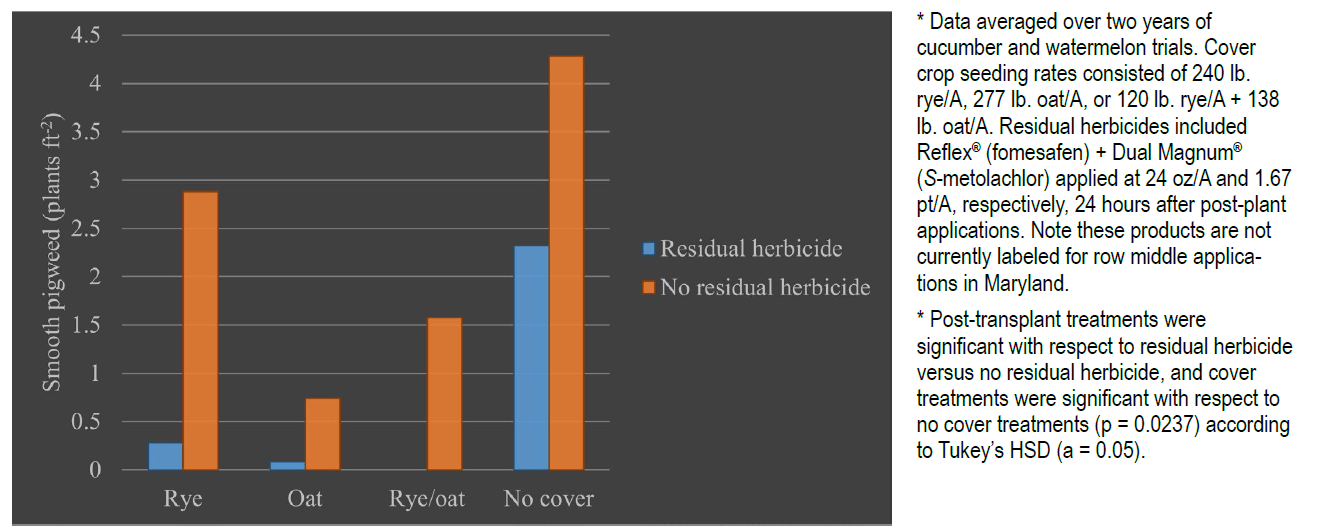

Including an additional residual herbicide, such as fomesafen (Reflex®) and/or S-metolachlor (Dual Magnum®) , at cover crop termination can help to extend the weed control period. Note that Reflex® and Dual Magnum® are not currently labeled for row-middle applications in Maryland. This is especially beneficial when trying to manage grasses and small seeded broadleaf weeds such as pigweeds that have yet to germinate. University trials showed that while cover crops alone reduced late-season smooth pigweed density 59% compared to no cover crops, the inclusion of a residual herbicide with a cover crop reduced pigweed density by 95% (Figure 4).A bar graph showing the impact of residual herbicide on smooth pigweed density (plants/ft²) across four different cover crop treatments: Rye, Oat, Rye/Oat mix, and No Cover. Blue bars indicate herbicide use, orange bars indicate no herbicide. Pigweed density is lowest with herbicide use in all treatments, highest in the "no cover" treatment without herbicide.

Yield

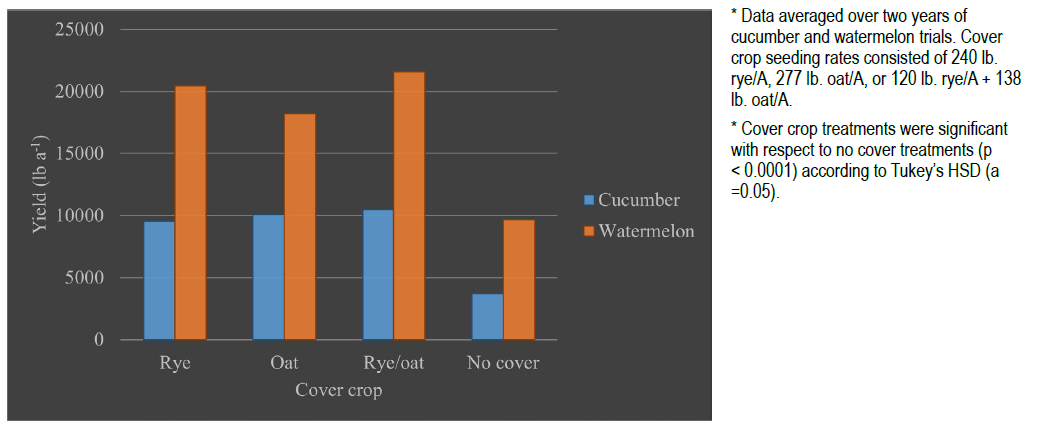

Incorporating spring-seeded cereal cover crops can improve yield. This may occur through the suppression of weeds that would otherwise compete with the crop. In university trials, cover crops increased cucumber and watermelon yields 170% and 107%, respectively, compared to no cover crop treatments, regardless of post-transplant herbicide (Figure 5). In addition, individual watermelons were 33% larger and individual cucumbers were 20% larger when cover crops were utilized compared to no cover crop.

How to Incorporate a Spring-Seeded Cereal Cover Crop

- Form beds and lay plastic in early spring (in Maryland, late March to mid-April).

- Broadcast seed the cereal cover crop between the plastic mulch rows. University trials have had success with seeding rates of 240 lb. rye/A, 277 lb. oats/A, or a mix of 120 lb. rye/A and 138 lb. oats/A. Rototilling the row-middles prior to cover crop seeding will improve stand uniformity and eliminate any weeds that may have germinated

prior to cover crop seeding. - Allow the cover crop to grow approximately 4 weeks before planting or transplanting a cash crop.

- Apply a post-transplant herbicide to control the cover crop and weeds after the cover crop has reached the jointing stage (Feekes 6.0 and beyond).

Additional considerations

Utilizing spring-seeded cereals as cover crops is not without its challenges. First, cover crops suppress weeds, but they will not eliminate them. Second, a standing cover crop (especially while acting as a living mulch), can compete with the vining cash crop or interfere with harvest. Third, effective post-plant herbicides will require the use of special equipment, such as hooded sprayers, as currently available and recommended herbicides are not registered for overthe- top applications in cucurbits. When using hooded sprayers, the standing cover may interfere with spray deposition inside the hood. Rolling or crimping the standing cover crop prior to an herbicide application can allow for more uniform spray coverage (Figure 6). While commercial sprayer/roller crimpers exist, this can also be accomplished by making a single tractor pass to knock down the cover crop with the tractor tires prior to applying herbicides.

Figure 6. A standing grass cover crop (a) may interfere with shielded herbicide applications (b). A single tractor pass (c) can help crimp the standing cover and allow for better spray coverage (d). Photo credits: Kurt Vollmer, UMD.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Crop Protection and Pest Management, Applied Research and Development Program through award #2020- 70006-33016. We would also like to thank Shore Seed, Syngenta, and Growmark for providing cover crop, watermelon, and cucumber seeds, respectively, as well as the farm and research crews at University of Maryland Wye Research and Education Center and the Rutgers Agricultural Research and Extension Center.

This publication was adapted from Integrated Weed Management in Cucurbit Production Using Spring-seeded Grass Cover Crops.

Commercial products are mentioned in this publication solely for the purpose of providing specific information. Mention of a product does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of products. Reference to commercial products or trade names is made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement by University of Maryland Extension is implied.

References:

- Cornelius, C.D., Bradley, K.W. (2017). Influence of various cover crop species on winter and summer annual weed emergence in soybean. Weed Technol. 31(4):503–513. https://doi.org/10.1017/wet.2017.23.

- Hirsh, S.M. (2024). Introduction to Growing Cover Crops in the Mid-Atlantic (FS-2023-0692). University of Maryland Extension. go.umd.edu/FS-2023-0692.

- Hirsh, S.M., Sater, H.M., Joseph, D.J. (2024). Cover Crop Planning (FS-2024-0743). University of Maryland Extension. go.umd.edu/FS-2024-0743.

- Vollmer, K., Joseph, D., Leslie, A., Hooks, C., Besançon, T. (2024). Integrated weed management in cucurbit production using spring-seeded grass cover crops. HortTechnology. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH05517-24.

- Vollmer, K.M., VanGessel, M.J., Johnson, Q.R., Scott, B.A. (2020). Influence of cereal rye management on weed control in soybean. Front Agron. 20(2):1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fagro.2020.600568.

KURT VOLLMER

kvollmer@umd.edu

DWAYNE JOSEPH

dwayne@umd.edu

ALAN LESLIE

aleslie@umd.edu

CERRUTI HOOKS

crrhooks@umd.edu

THIERRY BESANÇON

thierry.besancon@rutgers.edu

This publication, Spring-Seeded Cereal Cover Crops for Weed Management in Plasticulture Cucurbit Production (FS-2024-0736), is a part of a collection produced by the University of Maryland Extension within the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

The information presented has met UME peer-review standards, including internal and external technical review. For help accessing this or any UME publication contact: itaccessibility@umd.edu

For more information on this and other topics, visit the University of Maryland Extension website at extension.umd.edu

University programs, activities, and facilities are available to all without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, marital status, age, national origin, political affiliation, physical or mental disability, religion, protected veteran status, genetic information, personal appearance, or any other legally protected class.

When citing this publication, please use the suggested format:

Vollmer, K., Joseph, D., Leslie, A., Hooks, C., Besançon, T. (2025). Spring-Seeded Cereal Cover Crops for Weed Management in Plasticulture Cucurbit Production (FS-2024-0736). University of Maryland Extension. go.umd.edu/FS-2024-0736