FS-2025-0754 | August 2025

Soil Health

By Sarah Hirsh, Ph.D.

What is soil health?

Soil health is “the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans” (Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2025). A healthy soil has characteristics that will help support healthy and productive plants. Soil health is a similar concept to soil quality, which has been defined as “the capacity of a soil to function within ecosystem boundaries to sustain biological productivity, maintain environmental quality, and promote plant and animal health” (Doran and Parkin, 1994). “Soil health” emphasizes that soil should be recognized as a living, breathing ecosystem, which is home to billions of organisms.

We can consider soil in terms of its physical, chemical, and biological components. Some of these characteristics are inherent to factors that we cannot control, while others can be influenced by management. Soil health focuses on those characteristics that we can influence through management. For example, in normal farming operations we do not change soil texture (the percent of sand, silt and clay), which affects how that soil functions. In comparison to a soil with a higher clay content, a sandier soil will have lower water-holding and nutrient-retention capacity. However, regardless of the texture of the soil, if we manage the soil with practices that increase organic matter, we will increase water-holding and nutrient-retention capacity. In other words, we can improve soil quality and soil health through management practices regardless of the inherent soil texture.

Economic benefits of maintaining and improving soil health

Improved soil health leads to better plant growth and quality, which can directly translate to increased yields and profits. Healthier soils are more resistant (can withstand) and resilient (can bounce back) to periods of environmental stress such as heavy rain, drought, or pest and disease outbreaks. Healthier soils tend to drain water better, allowing for increased field access during wet periods. Management that emphasizes soil health practices can lead to reduced input costs by decreasing losses and improving use efficiency of fertilizer, pesticide and herbicide, irrigation applications, and tillage passes (Moebius-Clune et al., 2016). Practices that support soil organisms typically will increase the sustainability and profitability of the farm.

Soil biology

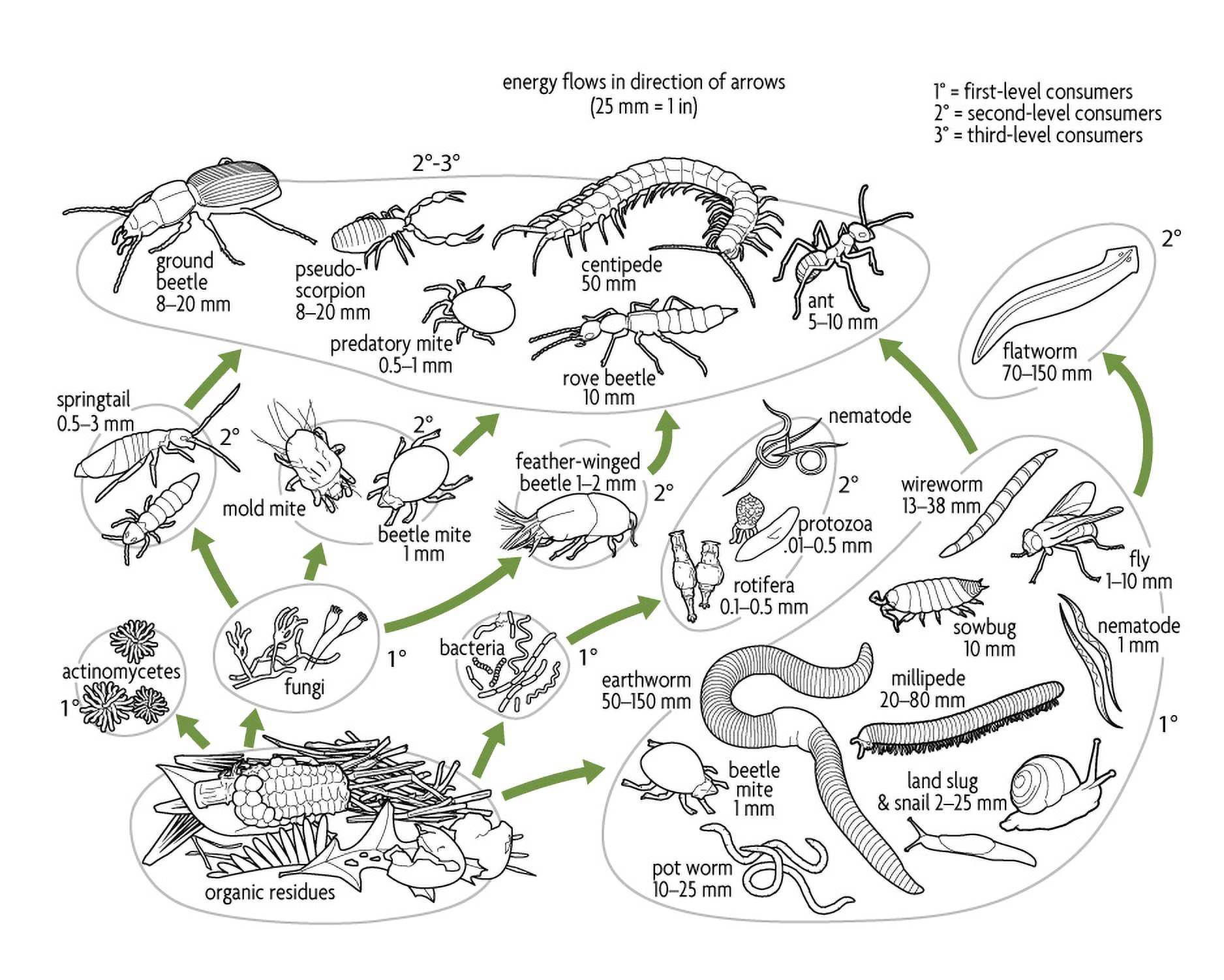

Soil organisms coexist in an intricate food web fueled by organic residues and root exudates, and play a central role in soil health (Figure 1). One teaspoon of agricultural soil typically contains 100 million to one billion bacteria, several meters of fungi, thousands of protozoa, and 10-20 nematodes (Fortuna, 2012). Soil organisms serve different roles and influence the physical and chemical components of soil. Organisms such as predatory insects, predatory nematodes, and parasites can help regulate the soil ecosystem by keeping pest numbers in check (Hopwood at al., 2021).

Physical components influenced by organisms

Organisms such as earthworms, ants, termites, and plant roots can change the formation of soil or serve as soil engineers. They form channels through the soil that facilitate water and oxygen movement and dispersal (Figure 2). Most soil organisms and plant roots are aerobic and need oxygen. Plant roots, earthworms, and many other organisms release sticky exudates that improve soil aggregation. An aggregated topsoil will include both large pores for water infiltration/percolation and aeration and smaller pores that hold water.

Chemical components influenced by organisms

Organisms are responsible for nutrient cycling in the soil. Bacteria, fungi, and earthworms help decompose organic materials in the soil. Decomposing organisms can transform nutrients from organic to mineral forms, or elements from one form to another, such as nitrifying bacteria that transform ammonia to nitrite and nitrate in the nitrogen cycle. Nitrate is a mobile nutrient form readily accessible for plant uptake. Soil organic matter retains water and nutrients, which are then available for plant uptake. Dead organisms or root exudates also serve as a food source and energy for other organisms. A sufficient food supply of organic materials drives the soil food web and encourages all the other activities and services of organisms (Figure 1).

Symbiotic relationships that influence soil nutrients

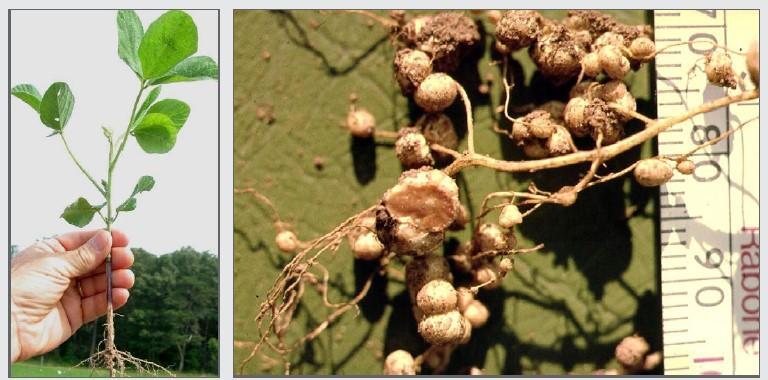

Rhizobia bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi are two examples of soil organisms that have symbiotic relationships with plants. Rhizobia bacteria form nodules on legume plant roots (Figure 3). Those nodules serve as factories, in which rhizobia transform atmospheric nitrogen gas (N2), a form of nitrogen that cannot be taken up by plants, to ammonia nitrogen (NH3), the form of nitrogen readily used by plants. This process is called biological nitrogen fixation. In turn, the rhizobia bacteria receive food and energy from the plant (Flynn and Idowu, 2015).

Mycorrhizal fungi grow within plant roots. Their hyphae scavenge phosphorus, other nutrients, and water from the surrounding soil, which they provide to the plant. In turn, they receive energy in the form of sugars from the plant. The hyphae are 1/60 the diameter of the plant root and therefore have access to much smaller soil pores than the roots can access (Magdoff and van Es, 2021). Mycorrhizal-plant relationships form with most vascular plants, with exceptions including spinach, sugar beets, lupins, and brassicas.

Management practices that encourage soil health

Considering the central role of soil organisms in improving soil health, we can build soil health by creating an environment that encourages a large and diverse population of soil organisms. This can be accomplished by following four key soil health management principles (Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2025):

- Minimize disturbance

- Maximize soil cover

- Maximize biodiversity

- Maximize presence of living roots

A variety of agricultural practices improve soil health, such as crop diversity, cover cropping, conservation tillage, and pasture and grazing.

Crop diversity

Crop diversity can be achieved through crop rotation, intercropping, or cover cropping. This involves not just growing different species, but growing those that fall within different functional groups. For example, if our primary crop is corn, then we could grow a cover crop that includes a brassica such as forage radish and/or a legume such as crimson clover.

Cover cropping

Cover crops are plants grown for a primary reason other than harvest, and are typically grown in the off-season. Cover cropping allows for living roots to be present during periods of time when cash crops are not typically grown, such as over the winter in a corn-soybean rotation. These roots offer many benefits such as forming channels through the soil to facilitate water and air movement and providing a food source and habitat for a diversity of soil organisms (Figure 4). Channels formed by deep roots can allow for deeper rainfall infiltration and a larger water reservoir in the soil (Figure 5). Cover crops also offer soil health benefits after they die. The dead material provides carbon and nutrients to other soil organisms, and carbon is built into organic matter. Any dead cover crop tissue that remains on the soil surface will cover the soil, serving as a mulch. This mulch will help hold moisture in the soil during drought periods and help preserve soil surface structure by reducing the impact force of rain droplets (Figure 5). The mulch can also help suppress weeds, helping farmers reduce their herbicide usage.

Conservation tillage

Conservation tillage limits the area of soil surface disturbance by tillage. Strip-tilling limits tillage to a 6-8” width per row, where the cash crop will be planted, but leaving the area between rows untilled. No-tilling decreases disturbance further, only exposing a very narrow width of soil during cash crop planting, while the soil surface remains largely undisturbed. Conservation tillage by itself helps keep the soil covered, as the residue from previous cash crops serves as a surface mulch. However, conservation tillage coupled with cover cropping can provide even more buffer against erosion-causing rain events through providing more cover on the soil surface (Figure 6).

Pasture and grazing

Pastures often include various perennial species, which form deep and intricate root systems that grow undisturbed for years. This improves soil structure and leads to an accumulation of organic matter, creating habitat and food sources for diverse soil organisms. Furthermore, the incorporation of grazing animals and their manure adds biodiversity and nutrients to the system.

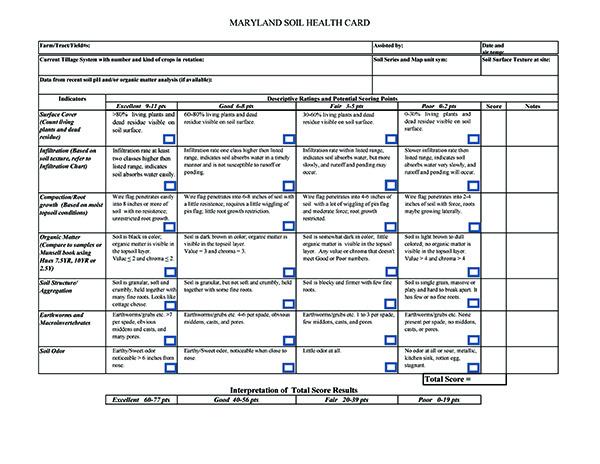

Measuring soil health

Soil health can be assessed in the lab and/or in the field. Several universities and private labs offer soil health testing. They will test biological, chemical, and physical parameters indicative of soil health. These tests can be costly. We can also track some measurements, such as organic matter, on a more affordable soil fertility test to help track soil health. Because increases in organic matter are often the result of soil health management practices such as no-till or cover cropping, we can measure soil health parameters in the field by simply digging and examining shovelfuls of soil. This works best when comparing two soils in close proximity to each other but with different management histories, such as a tilled area versus an untilled area of a field. A healthier soil will have better soil aggregation, a darker color, more soil organisms such as earthworms, and more roots (Figure 7). To assess how well the soils will stay aggregated when exposed to rain, we can place small clumps of soil in water; aggregates from the healthier soil will remain intact longer. To assess compaction, we can stick a wire flag in the ground to compare resistance. To assess infiltration, we can pour water into a metal ring hammered into the ground; a healthy soil will infiltrate faster. The Maryland Soil Health Card provides more details on in-field soil health testing (Figure 8; Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2018).

Summary

Soil health is the status of soil in terms of its ability to function and sustain life. It involves physical, chemical, and biological factors that are all interrelated. Soil organisms are critical for building good soil structure, ensuring air and water movements through the soil, decomposing organic materials, and cycling nutrients. A soil with good physical structure and with sufficient nutrient cycling will encourage increased numbers and diversity of soil organisms. When we manage soil with practices that minimize disturbance, maximize soil cover, maximize biodiversity, and maximize the presence of living roots, we can increase soil health, increasing the sustainability and profitability of agriculture.

Glossary terms

- Biological nitrogen fixation – process where rhizobia bacteria transform atmospheric nitrogen gas to ammonia nitrogen

- Conservation tillage – a type of tillage that limits the area of soil surface disturbance

- Cover crops – plants grown for a primary reason other than harvest and typically grown in the off-season

- Exudates – sticky substances released by soil organisms that improve soil aggregation

- Functional groups – groups of plant species that have similar biological characteristics and roles

- Hyphae – branching filaments of fungi

- Mycorrhizal fungi – fungi that form symbiotic relationship with plant roots

- Nitrate – negatively charged mobile form of nitrogen that is readily taken up by plants or leached

- Nodule – structure on legume plant root that house rhizobia bacteria

- No-tilling – a type of tillage that exposes only a narrow width of soil during cash crop planting, while the soil surface remains largely undisturbed

- Resilient – able to bounce back from periods of environmental stress

- Resistant – able to withstand periods of environmental stress

- Rhizobia bacteria – bacteria that live within nodules of legume plants and transform atmospheric nitrogen gas to ammonia nitrogen

- Soil engineers – organisms that change formation of soil such as earthworms, ants, and termites

- Soil health – the continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans

- Soil organic matter – complex mixture of organic substances that contains approximately 50% carbon

- Soil quality – The capacity of a soil to function within ecosystem boundaries to sustain biological productivity, maintain environmental quality, and promote plant and animal health Soil texture – the percent of sand, silt and clay in a soil

- Strip-tilling – a type of tillage that limits tillage to a 6-8” width per row where the cash crop will be planted, while the soil surface between rows is undisturbed

To learn more, consult these soil health resources:

- Clark, A. (Ed.). (2007). Managing cover crops profitably (3rd ed.). SARE, USDA. https://www.sare.org/resources/managing-cover-crops-profitably-3rd-edition/

- Doran, J.W. & Parkin, T.B. (1994). Defining and Assessing Soil Quality. In J.W. Doran, D.C. Coleman, D.F. Bezdicek and B.A. Stewart (Eds.), Defining Soil Quality for a Sustainable Environment, Volume 35 (pp. 1-21). Soil Science Society of America, Inc. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaspecpub35.c1

- Flynn, R., & Idowu, J. (Revised 2015). Nitrogen Fixation by Legumes. New Mexico State University. Guide A-129. https://pubs.nmsu.edu/_a/A129/index.html.

- Fortuna, A. (2012). The Soil Biota. Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):1. https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/the-soil-biota-84078125/

- Hirsh, S.M. (2024). Introduction to Growing Cover Crops in the Mid-Atlantic (FS-2023-0692). University of Maryland Extension. go.umd.edu/FS-2023-0692.

- Hopwood, J., Frischie, S., May E., & Lee-Mäder, E. (2021). Farming with Soil Life: A Handbook for Supporting Soil Invertebrates and Soil Health on Farms. 128 pp. Portland, OR: The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

- Magdoff, F., & van Es, H. (2021). Building Soils for Better Crops: Ecological Management for Healthy Soils (4th ed.). SARE, USDA. https://www.sare.org/resources/building-soils-for-better-crops/

- Moebius-Clune, B.N., Moebius-Clune, D.J., Gugino, B.K., Idowu, O.J., Schindelbeck, R.R., Ristow A.J., van Es, H.M., Thies, J.E., Shayler, H.A., McBride, M.B., Kurtz, K.S.M., Wolfe, D.W., & Abawi, G.S. (2016). Comprehensive Assessment of Soil Health – The Cornell Framework, Edition 3.2, Cornell University, Geneva, NY.

- Natural Resources Conservation Service. Maryland Soil Health Card. (2018)., U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://mda.maryland.gov/resource_conservation/counties/SoilHealthCard.pdf.

- Natural Resources Conservation Service. Soil Health. (2025). U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/conservation-basics/natural-resource-concerns/soils/soil-health.

- Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education. What is Soil Health? An Interactive Exploration of Soil Health and How to Improve It. (2019). U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.sare.org/resources/what-is-soil-health/.

SARAH HIRSH

shirsh@umd.edu

This publication, Soil Health (FS-2025-0754), is a part of a collection produced by the University of Maryland Extension within the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

The information presented has met UME peer-review standards, including internal and external technical review. For help accessing this or any UME publication contact: itaccessibility@umd.edu

For more information on this and other topics, visit the University of Maryland Extension website at extension.umd.edu

University programs, activities, and facilities are available to all without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, marital status, age, national origin, political affiliation, physical or mental disability, religion, protected veteran status, genetic information, personal appearance, or any other legally protected class.

When citing this publication, please use the suggested format:

Hirsh, S. (2025). Soil Health (FS-2025-0754). University of Maryland Extension. go.umd.edu/FS-2025-0754.