How to completely remove bamboo

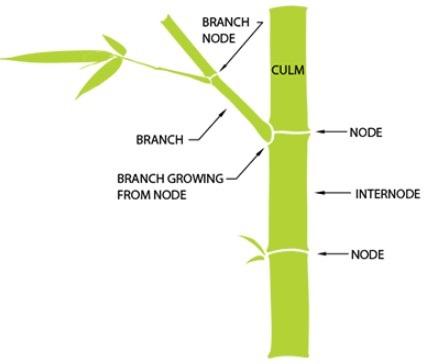

Non-chemical control involves physically removing as much growth as possible. The easiest are the culms (canes, stems) that sprout above-ground. The most difficult are the underground rhizomes, which allow the plant to spread for a hundred or more feet in any unobstructed direction. Rhizome removal is the fastest and most effective approach, but the trade-off is that it will be more disruptive to your landscape and cost significantly more.

Flocks of some bird species will roost in bamboo. For respiratory safety, wear a mask and gloves when cutting and removing culms where large numbers of birds are roosting, due to health hazards from accumulated bird droppings.

Cutting culms

The method of removal with minimal environmental impact is cutting culms. This may also be your only option if the colony is growing among desirable trees or other valuable landscape plants. As with any plant, continual removal of foliage deprives the plant of its way of feeding itself, thus eventually starving it to death. Energy stores are used in re-sprouting, and when they are not allowed to photosynthesize, the plant eventually runs out of energy. With bamboo, this process may take a long time, as much energy is stored in underground tissues. In addition, sprouts that appear outside of your yard, unnoticed or untreated, will continue to feed the root system and circumvent efforts to starve the plant. Therefore, for this method to work well, you must be thorough.

Tender new culms appearing in spring can simply be kicked- or knocked-over. Check for new shoots weekly as they grow rapidly. Culms that re-appear in summer will need to be cut down with loppers or a small folding saw with small razor-sharp teeth.

Removing rhizomes

Removing the rhizomes is another way to eradicate bamboo without resorting to herbicides. Hand removal is extremely difficult and requires sturdy tools and lots of effort. Some landscaping companies use power equipment, like mini-excavators, to lift rhizomes out of the soil after the culms are cut and removed. Such equipment will need room to maneuver in an established landscape or else plantings may be damaged. There will also be soil compaction during its use and possible regrading needed after removal. Any missed fragments of rhizome can re-sprout, so be prepared to cut new shoots at the soil level as soon as they appear.

For large bamboo patches, check with your local government to see if a permit is needed before excavating. Use erosion control measures to protect nearby surface water.

Chemical control

Herbicides should be the method of last resort and require non-selective, systemic products that are absorbed by plant tissues and transported down into the roots. (Glyphosate is one example of a systemic active ingredient.) Be careful with applications, as non-selective herbicides will damage desirable plants if spray drifts or drips onto them. Due to the waxy nature of bamboo leaves, herbicides may benefit from the addition of a spreader-sticker, which helps the spray adhere to the leaf. If you are in a wetland habitat or near open water, utilize herbicides manufactured for this environment only, with no surfactants.

When and How to Apply Herbicides

1. Don’t attempt to spray a mature stand of running bamboo without first cutting-down as much growth as you can. This greatly reduces the amount of herbicide needed and avoids you having to spray over your head.

2. Small, leafy shoots (under 5 feet tall) can be sprayed anytime during the growing season. Systemic herbicides are most effective when applied from mid-September to mid-October and repeated in 14 days.

3. Cut culms and spray or paint a non-selective herbicide on the pruning cut within 5 minutes of cutting.

How to dispose of bamboo

Unless you employ a landscaper who can haul away the removed debris, you may have a lot of material to dispose of. Cut culms can be dried and used as plant stakes, vine supports, or an array of craft projects; fellow gardeners may also eagerly take some off your hands. Contact your county or local landfill to ask about the acceptance of bamboo fragments as yard waste.

Alternatives for replacement

Native species would make excellent replacements for a stand of bamboo. As with any planting, consider your site conditions (summer sunlight exposure, soil moisture and drainage, soil type, deer issues) and desired wildlife benefits in order to narrow down your options. The lists linked below are great resources for helping with selection.

Grasses provide extra dimensions of interest in the garden in terms of movement and rustling sounds in a breeze. Such features provided by running bamboo can be supplied by other grasses, either clumping bamboo species or native grass species whose seeds can feed migrating or overwintering birds.

The evergreen appeal of bamboo can be substituted with other species, either grasses (which may not stay green but whose foliage will persist most of the winter) or broadleaf evergreens or conifers. Several achieve the large stature of bamboo and have fairly rapid growth.