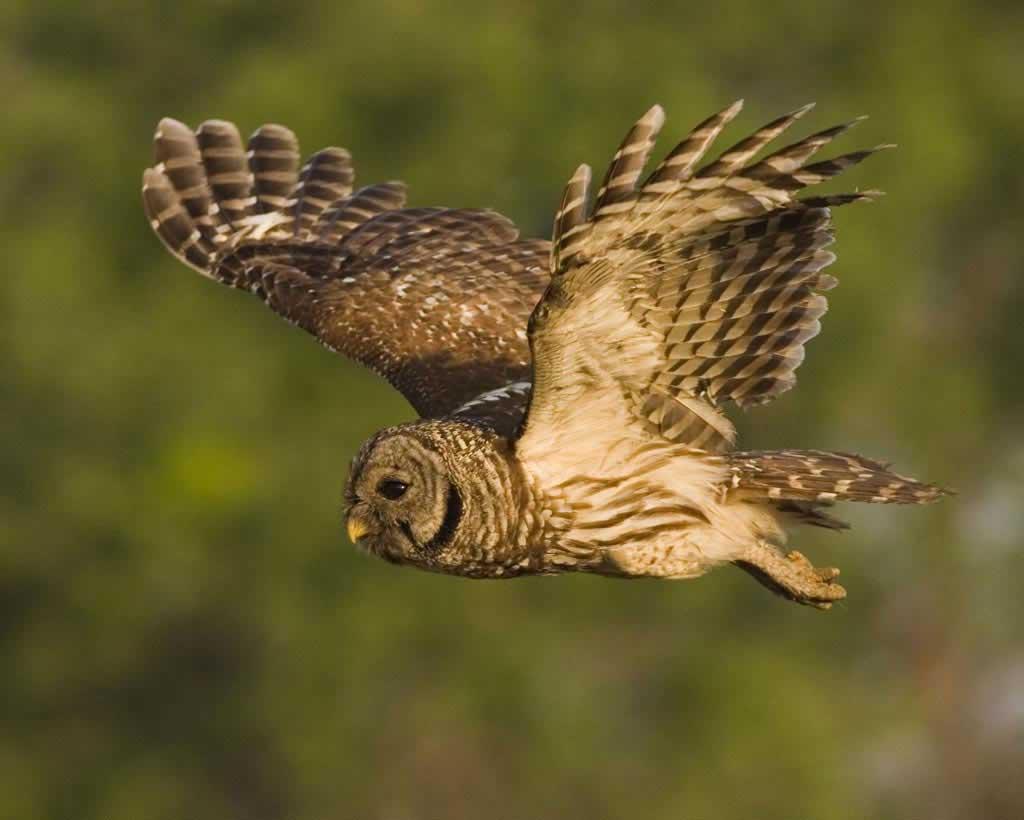

Barred owl in flight; photo courtesy Arthur Morris/VIREO

The barred owl (Strix varia) is one of North America’s most typical species. Originally an exclusively eastern bird, it is also known colloquially as the hoot owl, the laughing owl, and the swamp owl. It inhabits old growth woodlands, wooded river bottoms, and wooded swamps. Visitors to the outdoors enjoy the bird’s distinctive call that has been imitated by generations of youngsters at camp. The hooting “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you-all?” carries well through the woods as a pair call back and forth to each other. In addition, the barred owl has a variety of calls that include cackles caws, and hoots. Unlike other owls, they may be heard calling during the daytime.

This species is a large, stocky bird, with a rounded head, no ear tufts, and medium length, rounded tails. They range from 17 to 20 inches (43-50 cm) in length, with a wingspan of 39 to 43 inches (99-110 cm). Birds weigh from 17 to 37 ounces (470-1050 grams). Their feathers are mottled brown and white, with dark brown eyes that appear almost black. The feathers on the upper breast are crossed with horizontal brown bars; the tail feathers have equally distinctive three to five bars. Females are generally larger than males with similar plumage.

Barred owls perch in forest trees during the day and hunt generally near dawn or dusk. They fly through the woods with slow, methodical wingbeats, with occasional long, direct glides. They sweep down on their prey, capturing small animals, such as squirrels, rabbits, opossums, shrews and various rodents. The birds may also hunt frogs, salamanders, snakes and some insects as well.

Unlike some other birds of prey, barred owls are not migratory. In fact, most barred owls rarely move far from their home range. One study noted that of 158 birds that were banded and found later, none had moved farther than six miles away from where it had been originally banded. These owls need large, dead trees for nesting sites, usually choosing a natural cavity in a tree or taking over one excavated by pileated woodpeckers. When snags are not available, they may also take over a nesting area abandoned by other birds, such as hawks or ravens. It is unknown whether the male or the female picks the site, but scientists have speculated that they may study a particular spot for perhaps a year before choosing to use it.

Because barred owls are year-round residents, mating and breeding schedules vary across its range. During mating rituals, the woods come alive as both males and females screech, hoot and caterwaul. Pairs probably mate for life, raising one brood each year. If the first clutch of eggs is lost due to predation or other mishaps, the female may lay a second. Eggs are laid as early as mid-January in Florida or as late as mid-April in northern Maine. Clutches are usually 2-4 eggs and are incubated by the female. The eggs hatch approximately four weeks later, and the chicks fledge about a month after that. During this time, the male hunts and brings food for the female and the young. In the wild, barred owls can live about ten years; in captivity, they can live past twenty.

While some of the barred owl’s original habitat in eastern North America has decreased over the last one hundred years, the bird has used wooded river corridors to expand its range into the forests of the upper Midwest, the Rocky Mountains, and the Pacific Northwest, as well as the forests of southern Canada. Today it can be found from British Columbia to Florida, and from southern Quebec to east Texas.

Consequently, the species’ overall population is stable and actually increased during the last half of the 20th century. However, their preference for large, dead trees for nesting can put them at risk in heavily-logged areas. For that reason, the barred owl is often used as an indicator species for the management of older-growth woodlands.