Reminder to Scout For Aphids in Small Grains As Part of Your Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus Management

Kelly Hamby, Associate Professor & Extension Specialist, University of Maryland, and David Ownes, Extension Entomologist, University of Delaware; & Alyssa K. Betts, Extension Field Crops Pathologist, University of Delaware

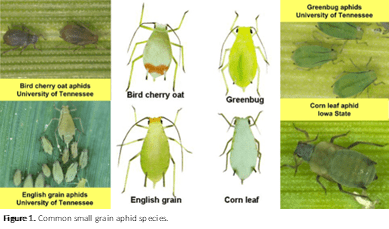

Aphid populations outbreak very quickly and should be regularly scouted. Four aphid species are commonly found in Maryland and Delaware small grains and their economic impact varies. Therefore, it is also important to determine which species you are finding. In the fall, greenbugs are of most concern for direct damage to small grains, whereas in the spring English grain aphids are of most concern. However, aphid management concerns primarily occur because aphids spread Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus (BYDV). BYDV losses are most associated with bird cherry oat aphids and fall infections of BYDV are the most damaging. In mild winters, aphid activity can occur in February and also cause concerning BYDV.

Identifying small grains aphids

A magnifying hand lens is required to identify aphids.

Bird cherry-oat aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi) ranges from orange green to olive green to greenish black. Wingless individuals typically have a reddish orange patch around the base of the cornicles (tail pipes). Winged individuals tend to be very dark. Their legs, cornicles, and antennae are similar in color to their bodies and medium in size.

Greenbug (Schizaphis graminum) ranges from lime-green to yellow and has a dark green line down the middle of their upperside. Both the legs and the cornicles are pale in color with noticeably darker tips. Cornicles are short. Winged individuals are similar but are darker around where the wings attach.

English grain aphid (Sitobion avenae) ranges from pale green to yellow or even reddish brown and tend to be larger than the other small grain species. They have long dark antennae that extend to or past half the length of the body and are the only species with long black cornicles. Winged individuals are similar to wingless individuals but are darker around where the wings attach.

Corn leaf (Rhopalosiphum maidis) ranges from light green to blue with dark heads, antennae, cornicles, and legs (usually all or most of each of these appendages is dark). The antennae and cornicles are shorter than the other small grain aphid species. Wing aphids are similar in size and darker than wingless individuals. This species tends to be much less common in small grain in our area.

Monitoring and Thresholds

Aphids should be monitored in the fall and at green up. Scout ten locations per field avoiding field margins and look at 1 ft of row in each, making sure to look at the crown (at or below ground level), at the stem, and on the undersides of leaves. English grain aphids tend to feed on the uppermost portions of the plants while bird cherry oat aphids tend to cluster on the lower portions, especially in barley.

University extension threshold recommendations vary by region. In the fall, we recommended a threshold of 6-8 aphids/row-ft in barley and 20 aphids/row-ft in wheat. In the early spring when small grains green up and resume growth, the aphid threshold increases greatly to 101-300 aphids/row-ft. It is unusual but not impossible for aphid populations to peak and require treatment even in late winter or early spring, as happened in Delaware in 2019 and 2022.

Keep an eye out for natural enemies that feed upon or parasitize aphids as they often do a good job of managing aphids. One natural enemy (lady beetle, aphid mummy, etc., for more information see 2023 Agronomy News Article) per 50-100 aphids is a ratio to avoid needing to actively manage aphids and natural enemies are great at finding aphid populations when they are too low for us to detect. Insecticides will kill natural enemies and which can result in aphid outbreaks.

Aphid Management

Aphid management relies heavily on planting date, varietal susceptibility to BYDV, insecticides, and natural enemies. Planting wheat later provides less time for aphids to colonize and reproduce in the fall. Wheat varieties have variable tolerance to BYDV, check with your seed dealer to determine your variety’s susceptibility. If it is more tolerant, you should be able to tolerate greater aphid numbers than a very susceptible variety. Insecticide seed treatments (e.g., Cruiser, Gaucho) provide some protection from fall aphids (4-6 weeks), but do not continue to provide protection into the spring and are not economic in years where aphids do not occur. In addition, they reduce natural enemy populations even into spring. Seed treatments may be more economic in malting barley than feed barley or wheat because malting barley is particularly susceptible to BYDV and high value. If a seed treatment was not used and aphid counts are at or near threshold in the fall, especially for bird cherry oat aphid or greenbug (due to direct feeding injury) foliar insecticide applications should be used. Pyrethroid insecticides (e.g., Warrior) or a pyrethroid-neonicotinoid mix (e.g., Endigo, labeled for barley only) are very effective for small grain aphids.

More Information

- Aphid Control in Small Grains in The Spring, University of Delaware, https://www.udel.edu/academics/colleges/canr/cooperative-extension/fact-sheets/aphid-control-small-grains/

- Preparing for 2026 Small Grains Disease Management, University of Delaware Weekly Crop Update, https://sites.udel.edu/weeklycropupdate/?p=27301

- Wheat Insect Guide Aphids, University of Tennessee, https://guide.utcrops.com/wheat/wheat-insect-guide/aphids/

- Scout for Aphids In Small Grains, Agronomy News, 2023, https://blog.umd.edu/agronomynews/2023/10/09/scout-for-aphids-in-small-grains/

- Barley Yellow Dwarf in Small Grains in the Southeast, https://smallgrains.ces.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/BYDV-in-the-SE-ANR-1082-compressed.pdf?fwd=no

This article appears in October 2025, Volume 16, Issue 7 of the Agronomy News.