How We Came to Have the ‘Monocacy’ Hop

Bryan Butler, Agriculture and Food Systems, Carroll County, University of Maryland Extension, 700 Agriculture Center, Westminster, Maryland 21157

Tom Barse, Milkhouse Brewery at Stillpoint Farm, 8253 Dollyhyde Road, Mount Airy, Maryland 21771

Nahla Bassil, USDA-ARS, National Clonal Germplasm Repository, 33447 Peoria Rd., Corvallis, OR 97333

Kim Lewers, USDA-ARS, Beltsville, Agricultural Research Center-West, Genetic Improvement of Fruits and Vegetables Laboratory, Bldg. 010A, 10300 Baltimore Ave. Beltsville, MD 20705

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by USDA Specialty Crop Block Grant Program through the Maryland Department of Agriculture’s SCBGP Agreement Number 221501-01, and by the USDA-ARS Projects 2072-21000-049-000-D and 8042-21220-257-00-D.

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by The University of Maryland or the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Discovery

The hop plant was found in the yard of Green Spring Farm in Frederick County, Maryland, in the late 1960’s by veterinarian, Dr. Ray Ediger. Green Spring Farm is located at 10521 Old Frederick Rd., Frederick, MD, 21701-1955, at latitude 39.3123N, longitude 77.2341W, and an elevation of 106 m. Although this hop plant’s prior history, origin and age are unknown, Green Spring Farm has been continuously farmed by the family of Dr. Ediger's wife, Louise, since 1886 (more than 135 years). The farm is part of the original Carrollton Manor, once owned by Charles Carroll, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. The Edigers took over farming at Green Spring in 1992 upon the death of Louise’s mother, Daisy Stull. Initially, it was a dairy and crop farm; the dairy cattle were subsequently replaced with beef cattle. When Dr. Ediger moved to the property and began to clean up the overgrown grounds around the farm buildings, he noticed the hop plant, recognizing it as a hop plant, and not just a vine-like weed, because he had grown up in Oregon and handpicked hops on a local farm in his youth to earn extra money during the summers. He thought it was interesting to have a hop plant in his yard, so he left it alone and allowed it to grow. The hop plant was very fortunate to be found by someone who recognized it. At the time, there were very few hop plants in Maryland and no hop yards. Although, prior to prohibition, approximately 10-20 % of the hops used in the breweries in Baltimore were grown in this area. Following prohibition, the production of hops left Maryland as well as most of the mid-Atlantic and moved to the Pacific Northwest and did not return until the early 2000s.

Dr. Ediger did not realize at the time how rare it was to have a hop plant growing on his farm. He allowed it to grow on the fence along the farm lane and then subsequently up and over the yard he built for his chickens and other farm fowl. The hop provided shade in the hot summer and died back each fall allowing the sun to shine into the yard, warming the area in the pen. The plant grew well and produced hop cones every year with no specific management other than clearing the dead bines in the spring. The plant received no insect, mite, or disease control whatsoever from the 1960s to the present and more than likely, nothing before then either. Dr. Ediger simply enjoyed the seasonal maturation and development of the plant each year and did not use the cones.

The plant is located near a farm lane that had been used to move cattle to and from the barn. The hop likely was planted in the corner of a cottage garden between the house and the barn, as was the practice. The soil the hop is growing in is a Readington silt loam with a 3-8 percent slope. The soil is deep to very deep, moderately well drained, and formed from weathered noncalcareous shale, siltstone, and fine-grained sandstone. It is medium textured with a strong medium granular structure, friable and slightly sticky. The mean annual precipitation is 43 inches, and the mean annual temperature is 53 ˚F.

Initial use in brewing

When Tom Barse, an avid home brewer since 1972, and Carolann McConaughy bought their farm in Mount Airy, Maryland, in the Spring of 2008, a one-acre hopyard of ‘Cascade’ and ‘Chinook’ hops was planted. Working with other Maryland farmers, brewers, and local elected officials, Tom helped get Maryland’s Farm Brewery law enacted in 2012 (https://maryland.lawi.us/2012-regular-session-hb-1126/). Shortly thereafter, Milkhouse Brewery at Stillpoint Farm was established, and the tasting room opened in June 2013. Tom and Carolann had established Maryland’s first Class 8 farm brewery.

In March, 2013, at an event honoring former Frederick County Farm Bureau president Tom Browning at Linganore Wine Cellars in Frederick County, Tom Barse met Dr. Ray Ediger and shared his interests in increasing his use of Maryland ingredients at his brewery (Fig. 1). Dr. Ediger shared the information about his hop and offered Tom some hop cones in exchange for a beer if Tom would use the hops in brewing. Tom brewed a few beers with it and felt the hop made a good addition to some of the beers at the Milkhouse Brewery due to its spicy, floral, and fruity aromatic qualities. Tom Barse shared his interest in the Green Spring Farm hop plant with some home brewers, who made a few very small batches of beer with a limited supply of cones combined with cones from other hops sources.

Propagation

Tom dug up a few rhizomes of the Green Spring Farm hop, and he and a couple of home brewers tried to grow the hop with somewhat limited success. The hop showed promise but was not being grown in a commercial setting where it could be managed to maximize quality and quantity. Although it does make rhizomes, it is somewhat more challenging to propagate through standard methods than some other commercial varieties.

In 2017, Bryan Butler, with the University of Maryland Extension (UME) propagated the Green Spring Farms hop using indoor two-node vegetative propagation from new bine growth. Vigorously growing bines were cut to two nodes and four leaves with the lower two leaves removed and one of the upper leaves removed. The lower ½ inch of the bine was moistened, dipped in Take Root Rooting Hormone, a 0.1% powder of Indole-3-butyric acid (United Industries, St Louis, MO, USA), and plugged into Southern States Premium Tobacco and Vegetable Mix potting soil (Southern States Cooperative Richmond, Va. USA) in 48-cell plug trays. The plugs were moistened and covered with clear plastic sandwich bags for 10-14 days to prevent the wilting while the roots developed on the bine plugs. Plants stayed in the plug tray for two more weeks and were then transplanted into 4-inch pots for at least four weeks to develop a strong root system that would begin to fill the pot (Fig. 2). The potted plants were hardened off by moving them outside to a shady area where the received about two hours of full sun per day and were transplanted to a field about two weeks later. This type of propagation proved to be much more effective than growing the plant from rhizomes.

Hop yard establishment

The Green Spring Farms hop plants were established in an existing Maryland hop trial in 2018 with 23 other varieties at the Western Maryland Research and Education Center (WMREC) in Keedysville, Maryland (Butler, 2018). Initially, collecting material to propagate was a bit of a challenge, and other factors played a role in delaying the first meaningful harvest until 2020. Unfortunately, two weeks prior to harvest, a severe storm destroyed the entire ½ acre hop yard making harvest of any quantity impossible. A new hop yard was established in 2022 at WMREC with approximately 200 plants of the Green Springs Farm hop genotype alone and managed as a commercial hop yard.

Plant description

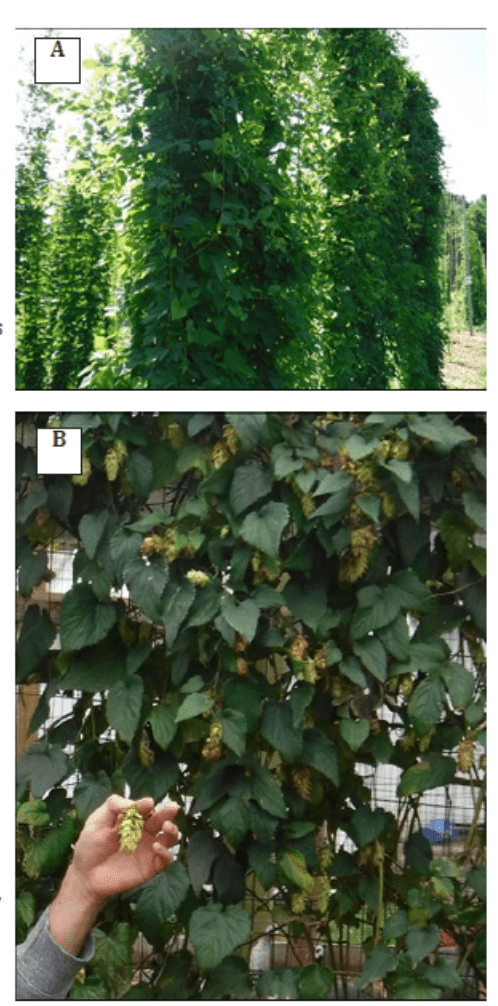

Like ‘Centennial,’ the Green Springs Farm hop has a clavate growth form (general thickening towards the distal ends). The hop grows primarily from a central crown and does not make many rhizomes; it is not a prolific spreader. The Green Springs Farm hop has noticeably robust bines, with a diameter two to four times that of ‘Centennial’. The hop is tall, growing 20 ft high in Maryland (Fig. 3); for comparison, a commercially grown hop in the Pacific Northwest is considered tall at 16 ft. The bines have very long lateral branches often exceeding 3m, much larger than ‘Centennial’ at around 0.6 to 1.3 m. The plants are large enough to slide down the support wires in a hurricane or thunderstorm but can easily be propped up again afterwards. The extensive lateral development has presented a challenge at times with mechanical harvest using a Hopster 5P (MitoTechnologies, Rochester, New York) but a WHE 170 hop harvester (Wolf Hop Harvesters, Wilkόw, Lubelskie Province, Poland) is capable of harvesting these large plants. Continued work on management, including plant spacing, support structures, pruning, shearing, and especially crowning is needed to increase yield and refine the optimal maturity time. Crowning in Maryland is done in early May to remove old growth from the previous year and the current year’s new growth. Most conventional varieties grown in Maryland mature in early to mid-August, but the Green Springs Farm hop has been harvested over a month later in late September to early October. Although the planting and its management must be maintained for this longer period, the harvest process is more pleasant in the cooler weather, and the less humid conditions facilitate drying.

The Green Springs Farm hop is more resilient than other cultivars in Maryland’s highly variable weather. It is tolerant of two-spotted spider mites, potato leafhoppers, and hop downy mildew caused by Pseudoperonospora humuli. This hop does become infected by powdery mildew, especially when it is not grown in an open environment; however, when infected, it does not appear to suffer a significant loss of vigor. To this point, successful control has been achieved with applications of 1 or 2% horticultural oil sprays (Damoil, Drexel Chemical Co., Memphis, Tennessee). The Green Springs Farms hop is easy to care for and makes a good photographic background or ornamental hop for a brewery entrance.

The large plant size represents the potential for very high yields. Indeed, the first harvest from Maryland hop plants is typically just a few ounces per plant, while the first yield from the Green Springs Farm hop wand almost a pound per plant. The true yield potential is not yet known, because measurements so far were conducted on plants that were not crowned.

The Green Springs Farm hop produces medium to large, open cones in large loose clusters on the laterals of the plant (Fig. 3B). They are distributed in the upper, outside half of the plant. Seedless cone average diameter is 18.6 mm and the length is 33.6mm. The average wet weight is 0.80g with 24% dry matter (DM); the average dry weight is 0.182g at 10% moisture. Cone bracts tend to be brown on the tips at maturity and average 15.8 mm long; the bracteole measurement averages 17.3 mm. The abundant yellow lupulin (the hop pollen containing the aromatic acids and oils that contribute unique scents and flavors to a beer) develops evenly from tip to base of the cones. The hop cones have an herbal-floral aroma.

Molecular fingerprinting

The robust growth, visually different architecture, and mildew and insect pest resistance of the hop plant found at Green Springs Farm made it stand out from the two hops cultivars grown by Tom Barse, ‘Cascade’ and ‘Chinook’. When Tom first found out about the hop, he initially believed it was probably an old ‘Cluster’ variety from one of the hop farms in Frederick County that existed in the 19th century. The hop plant at Green Springs Farm also was noticeably different from the several cultivars that were growing in the storm-damaged research plot at WMREC. Even so, it would not have been surprising to find that the hop plant found at Green Springs Farm was identical to an old cultivar previously used in Maryland brewing.

The US hop collection is maintained by USDA-ARS National Plant Germplasm System at Corvallis, Oregon in the National Clonal Germplasm Repository (NCGR). There, the identity and relatedness of hop plants are established through molecular fingerprinting by Dr. Nahla Bassil, a Plant Molecular Geneticist. Earlier, another hop plant had been donated to the University of Maryland Extension Service program by a family in Washington County, MD. The family thought the plant predated prohibition and had been grown and used by their family for several generations. Dr. Bassil determined that plant was in fact ‘Centennial’, released in 1991 by Washington State University (Kenny and Zimmerman, 1991).

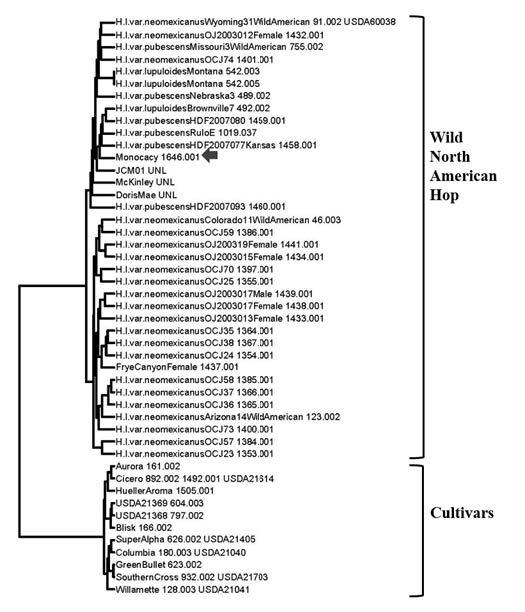

Dr. Bassil compared the DNA from the hop plant found at Green Springs Farm to that of 629 genotypes representing the majority (354) of the USDA ARS National hop collection, 249 diverse accessions from the USDA-ARS hops breeding program at Corvallis, and 26 from the University of Nebraska. The hop plant from Green Springs Farm was unlike all other genotypes in the comparison, was unrelated to the included cultivars, and was most similar to wild American accessions from the NCGR (Fig. 4).

Dr. Ediger, Tom Barse, and Bryan Butler decided to name the hop plant from Green Springs Farm ‘Monocacy’, because the plant was found in the Monocacy River Watershed, and all three individuals have farms in the watershed. Dr. Ediger donated the hop now known as ‘Monocacy’ to Bryan Butler and Tom Barse to research and determine the usefulness of this hop for brewers in Maryland, and beyond, for its characteristics for bittering, aroma, or for breeding to increase tolerance to Mid-Atlantic climate and pest pressures. ‘Monocacy’ is available from the NCGR for research purposes, and information about it, under PI 700807, CHUM 1646.001, is available at https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/accessiondetail?id=2138182.

Chemical composition

Once it was determined that ‘Monocacy’ was unique, its cones were tested for chemical (acids and oils) composition, and additional chemical composition tests have been made each year to ensure consistency. The hops were tested by Advanced Analytical Research (AAR) of Madison, Wisconsin. The hop has unique acid and oil components, which suggested that a lighter beer, using several different hopping methods would best reveal its contributions to flavor. The total oil content was 0.31 ml/100g. The hop had a 0.56 ratio of alpha to beta acids; alpha acid was 2.73% and beta acid was 4.88%. Cohumulone composition was 52.5% and colupulone was 74%. The 0.54 to 0.59 ratio of alpha to beta acids has not been problematic in the brewing process so far, but it is rather unusual, a reverse of most hops, and could contribute to a beer that is not overly bitter. With low alpha acids, the hop seems appropriate to be a potential aroma hop like U.S. Saaz, Fuggle, or Crystal, but with the very high beta acid it might have some bittering potential in certain lighter bodied beers.

Essential oils include unusually high myrcene and caryophyllene components, which tend to lend a strong “hoppy” aroma of fresh hop, an earthy flavor and clove-like spicy note, as well as a stone-fruit sweetness in the aroma of a beer. The composition of the major essential

oils for ‘Monocacy’ averaged 12.85% myrcene, 1.39% humulene, and 38.13% caryophyllene. The caryophyllene qualities can get lost with heat and do best in a dry hop environment in most beers. The higher myrcene and caryophyllene suggest a similar oil composition to Central European "Saazer" type of hops, which are also spicy and floral in character, as well as very low in alpha acid.

Additional use in brewing

Brewing evaluations of ‘Monocacy’ have been favorable. The floral, spicy, and fruity characteristics are more evident in lighter beers compared to other Maryland grown hops. Prior to chemical analysis by AAR, the hop was utilized by Milkhouse Brewery as a finishing hop in pilot batches, frequently in the whirlpool, or more often as a dry-hop to finish various cask ales served at the brewery. ‘Monocacy’ added an earthy and spicy note to lighter beers, and in some beers when used as a dry hop it added a light fruity note on the pallet in the finish.

The first single hop beer was made with ‘Monocacy’ in the Fall of 2020. To maximize the flavor and aroma components of ‘Monocacy’, a medium bodied “American Style” pale ale was brewed using all Maryland grown grain and using ‘Monocacy’ for all phases of the brewing process including in the boil for bittering, at flame-out in the whirlpool for flavor, and for dry-hopping in the fermenter for aroma. This beer was brewed as a half-barrel experimental brew. Hops for this brew were hand-picked in late September/early October 2020 from the original ‘Monocacy’ plant on Green Springs Farm. The hop cones contained 26 per cent dry matter when harvested and were dried in an oast to 92 per cent dry matter over screens with air flowing at 100 ˚F. After drying, the hop cones were not overly friable and maintained reasonable shape and continued to be highly aromatic. Hops were vacuum sealed and kept at 38 ˚F. until brew day.

The beer was brewed on October 26, 2020. The grain bill included Maryland-grown and -malted pale malt, as well as Maryland-grown and -malted Pilsner, Munich and malted wheat. The brewing process started with an infusion mash at 150 degrees Fahrenheit for one hour, then ½ hour vorlauf (circulation of wort), and after sparging (rinsing the grains to remove sugar from the grains while transferring the wort into the brew kettle), the kettle-full original specific gravity reached 1.041. Due to the low alpha acid content of ‘Monocacy’, wort was boiled for 60 minutes with the equivalent of 1.55 lbs. of the hop per barrel. Then the equivalent of 0.775 lbs./barrel of hops were added at flame-out (turning off the heat) during whirlpool (spinning the wort so the solid matter collects at the center and falls to the bottom of the brew kettle). Wort was chilled to 68 ˚F, fermented through primary fermentation and the equivalent of 0.775 lbs. of hops were added for dry hopping. After fermentation was complete, final specific gravity was 1.006. Then it was transferred to the bright tank to clear. The beer was carbonated to 2.8 volumes of CO2 and bottled in 500 ml bottles for release in December of 2020.

Launch

One 7 February 2023, the Brewers Association of Maryland, Milkhouse Brewery at Stillpoint Farm, the University of Maryland Extension, and Grow & Fortify hosted the inaugural tapping of three beers made with ‘Monocacy’ hop: an American Lager, a Vienna Lager, and a pale ale. Present were several dignitaries, including the Maryland Secretary of Agriculture, Mr. Kevin Atticks. Samples were distributed to participants for sensory evaluation using spider charts. Each participant was allowed to select a bottle of their favorite of the three ales to take home (Fig.5).

The beer’s final alcohol by volume (ABV) is 4.5, and international bitterness unit (IBU) is 23. The beer had a medium-light body with a bisquity malt aroma and delicate “spicy/hoppy” nose. The flavor was lightly malt forward (more malt than bitterness) with a noticeable earthy hop flavor, mild bitterness, and a spice note at the beginning of the pallet with a distinct but light stone fruit sweetness at the back of the pallet. The hop notes were reminiscent of a mix of ‘American Saaz’ and ‘Southern Cross’ from New Zealand. First impressions of brewing exclusively with this hop were that it is worth much more study. It has good finishing characteristics, and should make an interesting addition to any lighter beer such as a Kolsch, pale ale, lighter lagers, amber ales, lighter Belgian style ales, etc. __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________