Spring Termination of Cover Crops - How Timing Affects Crop Stands and Yields

Ray Weil and Cassandra Gabalis Department of Environmental Science and Technology

Summer 2024 saw extreme drought conditions in Maryland, including at the Central Maryland Research

and Education Center (CMREC) farm in Beltsville, MD. May rainfall was about normal, but the following summer months had almost no rain at all (Figure 1). With the severe drought, the cover crops had a clear effect on conserving summer soil moisture, and the use of winter cover crops affected corn and soybean yields.

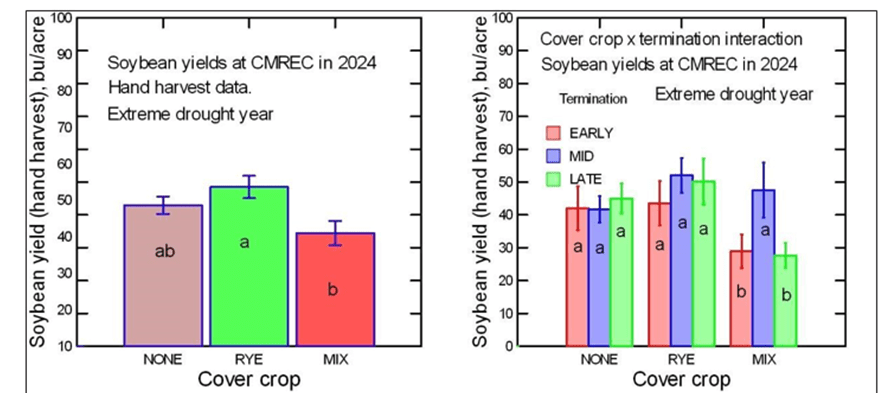

Soybean yields were determined by hand-harvesting. Averaged across in both sandy loam and silty clay loam soils (fields 39A and 7E) and all termination timings, soybean yields in plots with a preceding rye cover crop were significantly higher than in plots with a preceding cover crop clover-rye-radish mixture (Figure 2, left). Looking more deeply into this data, we see that the depressing effect of the clover-rye-radish MIX cover crop did not occur for the mid-termination (planting green and terminating at the same time in early May). Termination timing did not affect soybean yields for the no cover (weeds only) or rye cover treatments.

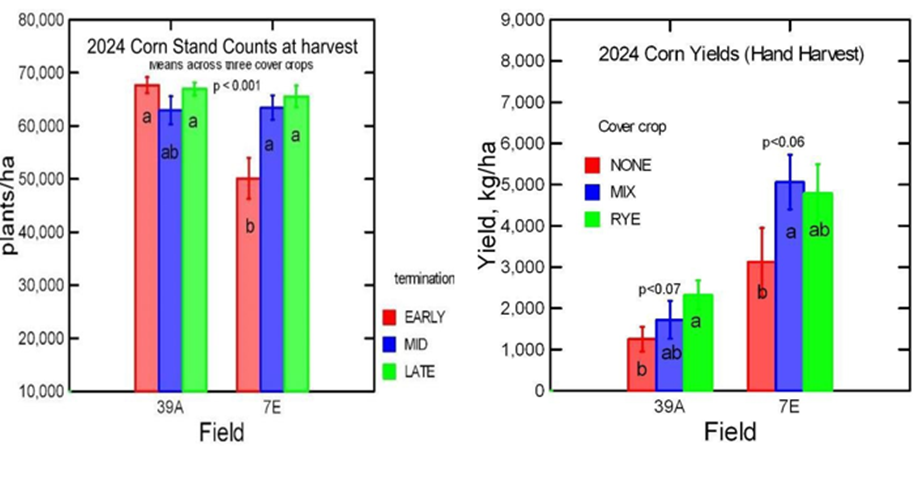

Corn yields and stand counts were determined in two adjacent 6.1 m lengths of row at the center of each plot. Differences in corn stand counts (Figure 4, left) were observed on the silty soil, with early cover crop termination resulting in lower corn stand counts than mid or late termination. In both fields at CMREC-Beltsville corn yields were very low due to severe drought, but higher corn grain yields (Figure 4, right) occurred where cover crops were used. In the sandy field, corn following a rye cover crop yielded higher than corn following no cover crop. In the silty field, corn following a cover crop mixture yielded higher than corn yields than corn following no cover crop. The immediate benefits of high-biomass cover crops and planting green tend to show up most clearly during drought-stressed years.