FS-2025-0759 | October 2025

Common Soybean Pests in Maryland

By Hayden Schug, AgFS Educator, University of Maryland Extension-Charles County and Dr. Galen Dively, University of Maryland.

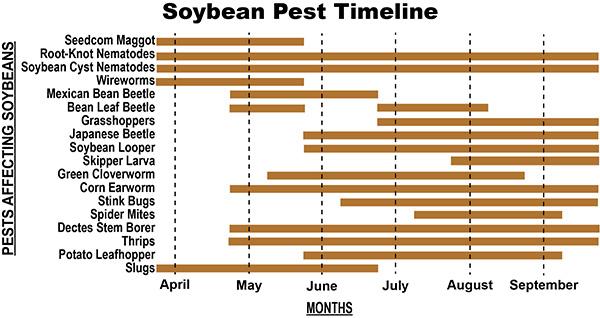

This publication is a revision of two previously published fact sheets titled Soybean Insect Pests I and II by Dr. Galen Dively of the University of Maryland Extension. It incorporates updated pest biology and identification and includes new insect pests now found in Maryland soybean fields, while also providing current integrated pest management (IPM) recommendations. This publication serves as a broad overview of common soybean pests in Maryland. Pest species typically appear at different times throughout the year, so scouting efforts should focus on specific pests during particular months. Figure 1 shows a general timeline of when most of these soybean pests are active and can help guide scouting.

To support easier identification, pests in this publication have been grouped into five broad categories: soil-inhabiting pests, defoliators, defoliating caterpillars, flower/pod/seed feeders, and other pests. Some species may fit into more than one category, but they have been placed where they are most likely to cause economic harm. For more detailed information on management strategies, life cycles, and treatment thresholds, readers are encouraged to consult the additional extension resources referenced in this publication.

the growing season in the Mid-Atlantic region. This chart helps guide scouting and management efforts from

planting through harvest.

I. Soil Inhabiting Pests

Seedcorn Maggot

The seedcorn maggot attacks a wide variety of vegetable and field crops, including soybeans in the Mid-Atlantic area. In the spring, the brownish gray flies lay eggs on seeds or just below the surface and prefer ground that is high in decayed organic matter. The maggots burrow into sprouting soybean seeds and young shoots, causing the destruction of the germ or the development of weak, spindly seedlings. Injury is more prevalent during cool, wet springs that delay germination, allowing for more damage from the maggots. Full-grown maggots are yellowish white, tough-skinned, legless, and about ¼ inch (6mm) long.

Root-Knot Nematodes

Root-knot nematodes (Figure 2) are microscopic roundworms that infect soybean roots, causing swelling and gall formation that interfere with nutrient and water uptake. These nematodes are more common in sandy soils but can be found in a variety of field conditions. Above-ground symptoms include stunting, yellowing, and reduced vigor, often resembling drought stress or nutrient deficiency. Below ground, root symptoms include the formation of galls, which vary in size and number depending on the level of infestation. These nematodes also reduce the number of nitrogen-fixing nodules, further limiting plant growth. Severely affected plants may wilt prematurely or have poorly developed root systems, leading to significant yield losses. Root-knot nematodes overwinter as eggs in the soil or within infected plant roots. In the spring, juveniles hatch and penetrate roots, establishing feeding sites. Their feeding causes root cells to enlarge, forming the characteristic galls. As they develop, females lay eggs in a gelatinous mass outside the root, allowing new juveniles to emerge and continue the cycle. Multiple generations may occur in a single growing season, especially if the season is particularly warm. Management of root-knot nematodes involves rotation with non-host crops to help reduce nematode populations over time. Resistant soybean varieties are available and should be used when planting in infested fields. Nematicides are available for management but are typically cost-prohibitive for soybean production. Regular soil sampling and nematode testing can help determine infestation levels and guide management decisions. More information can be found in the University of Maryland Extension publication General Recommendations for Managing Nematodes in Field Crops (FS-1082).

Soybean Cyst Nematode

Soybean cyst nematode (SCN) (Figure 3) is one of the most economically significant soybean pests in the Mid-Atlantic region. It often causes yield losses without obvious above-ground symptoms, making it a “silent yield robber.” Infestations may present as stunting, yellowing, and poor plant vigor, often in irregular patches within a field. Because SCN feeds on soybean roots, it reduces nodulation and interferes with nitrogen fixation, further limiting plant growth. Below-ground symptoms include tiny white or yellow cysts attached to the roots, which later turn brown as they mature. These cysts contain hundreds of eggs that can persist in the soil for years, allowing SCN populations to build over time if not properly managed.

SCN overwinters as eggs within cysts, which are highly resistant to environmental conditions. In the spring, juveniles hatch and infect soybean roots, where they establish feeding sites. As they develop, females swell into cysts while continuing to feed. Each cyst can produce hundreds of eggs, allowing populations to increase rapidly. A single SCN generation can develop in 25-30 days, leading to multiple generations per season under favorable conditions.

Management of SCN relies on an integrated approach, including resistant soybean varieties, crop rotation, and soil testing. Although resistant varieties are available, most rely on the same primary source of resistance. Over time, continuous use of this single resistance source has allowed nematode populations to adapt, which reduces its effectiveness. A few alternative resistance sources do exist, but they are limited. As a result, rotating among available resistant sources is recommended, even though the options are somewhat limited. Rotating with non-host crops such as corn, wheat, or alfalfa helps lower nematode numbers between soybean plantings. Soil testing every few years can help monitor SCN levels and inform management decisions. In fields with high SCN populations, nematicide seed treatments may provide early-season suppression, but they should be combined with other management strategies for long-term control. More information can be found in the University of Maryland Extension publication General Recommendations for Managing Nematodes in Field Crops (FS-1082).

Other soil-inhabiting pests

Cutworms, wireworms (Figure 4), and white grubs (either June Beetles, Japanese Beetles, or Masked Chafers) are occasionally linked with injury to soybean seeds and seedlings. Some of these insects, especially wireworms, are more prevalent in fields following turf or fallow fields. To scout for these insects, examine the soil in areas where plants have failed to emerge or around wilted or stunted plants. Examine ungerminated seeds and the underground stem or roots of wilted seedlings for injury and the presence of insects.

II. Defoliators

Soybean defoliators are typically managed as a complex, meaning multiple species contribute to overall leaf loss throughout the season. Instead of targeting individual insects, management decisions are based on the total percentage of defoliation observed across all defoliating pests. Defoliation should be assessed across the entire canopy, so it is important to examine the whole plant, not just the upper leaves, when estimating damage. Thresholds for treatment depend on the crop’s growth stage, 30% defoliation before bloom (vegetative stages) and 20% defoliation from bloom through pod fill (R1 to R6). Regular scouting is essential to monitor cumulative defoliation and prevent economic losses, especially when multiple pests are active at the same time.

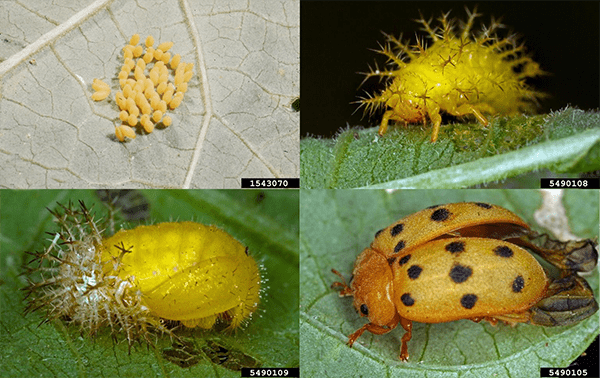

Mexican Bean Beetle

The Mexican bean beetle is a major defoliating pest of soybeans in the Mid-Atlantic area. Adult beetles overwinter in hedgerows, ditch banks, and woodlands near host crops. They become active from late April through May and may begin feeding on soybeans soon after seedlings emerge. Adults are slightly oval, about ½ inch (8mm) long, and yellow to coppery brown with 16 black spots on the wing covers. They usually feed and mate for several weeks before laying eggs. The yellow eggs are elliptical and normally occur in clusters of 40 to 50 on the undersides of leaves. Each female may lay an egg mass every 2 or 3 days, producing an average of 500 eggs. In spring, eggs hatch in 10 to 14 days, while during the summer, they hatch in 5 or 6 days. The larvae begin feeding gregariously and then move around on the plants, where they continue to feed for 2 to 4 weeks.

The yellow larvae (Figure 5) are about twice as long as wide, taper posteriorly, and have six longitudinal rows of branched spines. Mature larvae attach themselves by the end of their abdomens to the undersides of lower leaves and pupate. Pupae are yellow and oval, with the partially shed larval skin surrounding the posterior. They are found on the lower leaves and move only slightly. Adults emerge in about 10 days and lay eggs. Generation time from egg to adult is about 30 to 35 days. Two or more overlapping generations develop in the Mid-Atlantic area each year.

If overwintering populations are high, seedling damage may occur, though feeding injury usually does not reach economic levels before August. Early planted full-season soybeans usually attract more colonizing adults than later fields. However, doublecrop fields may become infested with adults who are moving out of maturing fields in search of more tender foliage. Older larvae and adults consume significant amounts of foliage. On the undersides of leaves, the tissue is stripped away between the veins, leaving the upper surface intact. This type of injury gives the leaves a distinctive lace-like or skeletonized appearance. Adult beetles also may eat irregular holes, especially on the tender, young leaves. Feeding injury can reduce soybean yield if the amount of defoliation exceeds 30 percent before R1 or 15 percent after R1.

The mid-summer weather can be a major limiting factor that determines the intensity of late-season infestations. Hot, dry conditions during July and August cause high mortality of eggs, young larvae, and pupae. Adult beetles also stop laying eggs when temperatures exceed 85°F.

Bean Leaf Beetle

Overwintered adults of the bean leaf beetle (Figure 6) often invade soybean fields shortly after plant emergence. They can kill seedlings by damaging the cotyledons before the first leaves develop, destroying the growing point and ultimately killing the plant. However, this damage is typically not economically significant as surrounding plants may be able to compensate for stand loss. Bean leaf beetles are about ¼ inch (6mm) long and can be green, yellow, tan, or red, with a distinct black margin around the outer edge of the wing covers. Each wing cover usually, but not always, has three black spots.

Check for beetles as soon as the plants emerge, starting with field margins near overwintering areas from where adults are likely to move in. Determine the infestation pattern, as feeding injury is often unevenly distributed early in the season. Estimate the level of stand reduction if seedlings are killed or assess the percentage of defoliation on older plants. This will help determine whether replanting is necessary or if defoliation thresholds have been reached, in which case treatment may be required. Bean leaf beetles prefer tender plant tissue and leave rounded holes in the leaves. This type of leaf injury is distinguishable from the lace-like damage caused by Mexican bean beetles.

Grasshoppers

The image shows three small, green grasshoppers sitting on a green leaf. The grasshoppers are nymphs, indicating they are in an immature stage. They have bright green bodies with black markings on their legs and antennae. The leaf they are on has several irregular holes along the edges, suggesting feeding damage caused by the grasshoppers. The background is blurred, highlighting the grasshoppers and the leaf in the foreground.

Several species of grasshoppers (Figure 7) invade soybean fields in the Mid-Atlantic area, particularly during the latter half of the growing season. Both adults and nymphs are general feeders on small grains, corn, forage crops, and various weeds in ditch banks and fencerows. They move into soybeans as these host plants are harvested, mowed, or dry out. Damaged plants appear ragged (Figure 8) with only the larger leaf veins intact. Scout for grasshoppers starting at the perimeter of the field moving in, grasshoppers tend to congregate at the edge of fields and then travel inward. Consult the economic thresholds established for soybean defoliation to determine the proper control measures.

Japanese Beetle Adults

Japanese beetles (Figure 9) seldom cause economic injury to soybeans as damage typically occurs during vegetative growth when defoliation thresholds are higher and soybeans can more readily compensate for vegetative damage. However, their presence in localized spots is often alarming. They feed gregariously on the upper foliage during July when soybeans are growing rapidly. Stringy, black excrement is associated with heavy defoliation. After July, the population naturally declines and no longer poses a threat.

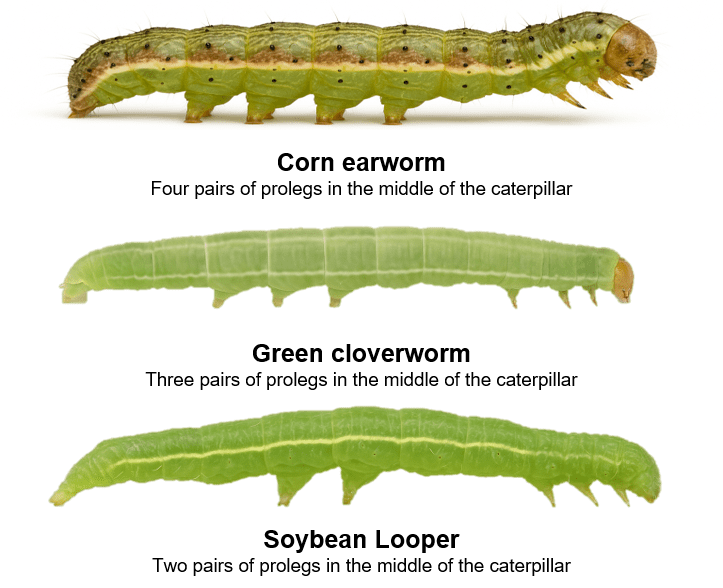

III. Defoliating Caterpillars (Figure 10)

Soybean Looper

The soybean looper (Figure 11) is a defoliating pest of soybeans that can cause yield losses when populations reach high levels. These caterpillars are light green with white longitudinal stripes along their bodies and have two pairs of prolegs. They grow to about 1 ½ inches (38 mm) long when fully developed. Soybean loopers primarily feed on the upper canopy, consuming leaves between the veins and leaving behind a skeletonized appearance. They typically arrive in soybean fields later in the growing season, as they migrate northward from southern overwintering areas. Soybean loopers prefer to feed on more mature plants and can rapidly strip foliage, especially during pod development. Natural enemies such as parasitoids and fungal pathogens often help regulate populations, but scouting is essential, particularly in late summer when infestations tend to peak, and soybeans are in their reproductive growth stage with a lower economic threshold for defoliation.

Skipper Larva

The mature silver-spotted skipper larva (Figure 12) is striking in appearance. It has a dark brownishred head with large, round, bright orange eye spots, a narrow brownish-red collar behind the head, and a greenish-yellow body 1.5 inches long (38mm). Normally, the larva infests common locust and other wild legumes in the Mid-Atlantic area.

The adult is a dark, chocolate-brown butterfly with white or pale yellow spots on the forewings. It is found around flowers and has a dashing, abrupt flight pattern. During late May through June, eggs are deposited singly on the undersides of the outer leaves. Eggs usually hatch in less than a week. Larvae appear in June but seldom reach damaging levels until September. After feeding for about 2 to 3 weeks, mature larvae drop to the ground and form cocoons in surface trash. Two or three generations occur each year.

Young larvae construct a “folded leaf” nest (Figure 13) by neatly cutting two slits on one side of a leaf. The small leaf piece between the slits is then folded over to form a roof, which is kept in place by silken strands. As larvae grow older, they fold over the entire half of a leaf or attach several leaves together with silk to form a leafy shelter for protection from weather and predators. Larvae feed on the foliage mostly at night and usually stay concealed in their nests or shelters during the day. Older larvae are voracious feeders and are capable of inflicting heavy foliage losses. Damaged foliage appears ragged with only the larger leaf veins intact.

Green Cloverworms

Green cloverworms (Figure 14) are pale green with two white longitudinal stripes on each side and are 1 1/4 inches (32mm) long when fully grown. They have three pairs of prolegs and thrash violently when touched, separating them from other pest caterpillars that have a different number of prolegs or curl up when touched. This insect is present in almost every soybean field each year but only occasionally reaches economic status in the Mid-Atlantic area when vegetative damage exceeds established thresholds. The charcoal-colored female moths with mottled wings lay their eggs singly on the undersides of leaves. Young cloverworms scrape the leaf tissues, leaving feeding areas that resemble irregular, shiny windows on the leaf surface. Older larvae eat irregular holes between the main veins, giving leaves a tattered appearance. Larvae appear on soybeans during July, peak in mid-August, and decline during September. Parasites, predators, and particularly a fungal disease play a major role in controlling this pest. Cloverworms killed by the fungus become hard, mummified, and covered with powdery white to light green spores. The presence of diseased worms usually signals the decline of the pest population.

Other Caterpillars

Yellow woollybear and saltmarsh caterpillars are sporadic defoliators of soybeans late in the growing season. These caterpillars are covered with long and short hairs and may be yellow, brownish-yellow, red, or white. A mature larva may be as long as 2 inches (51mm). All stages of these caterpillars feed voraciously on soybean foliage. Localized outbreaks occur in the Mid-Atlantic area, but dense populations often are decimated by virus and fungal diseases.

IV. Flower, Pod, and Seed feeders

Corn Earworm

The corn earworm (Figures 15 & 16) feeds on reproductive parts of soybeans later in the season, especially in the southern portion of the Mid-Atlantic area. Adult moths emerge in June or migrate up from the south in July and oviposit primarily on corn. After they emerge out of corn, they then move into other host crops such as soybeans. Moth activity increases significantly after mid-August as adult females shift their egg laying from corn to soybeans and late vegetable crops. Earworm outbreaks often follow a mid-summer drought, which causes the corn to ripen earlier and become less attractive to the moths.

Female moths prefer to lay eggs in open-canopied, blooming soybean fields. Drought conditions also delay soybean maturity and prevent normal canopy growth, so peak moth activity is more coincidental with the blooming of open-canopied fields.

Pheromone traps and computer modeling help to determine when and how many moths are active. Drop cloth sampling (Figure 17) or sweep netting are also useful scouting tools for assessing corn earworm pressure. This method captures insects dislodged from the canopy and helps evaluate whether thresholds are met for treatment. If a damaging population is present, wait until most of the larvae are ½ inch (12mm) or more in length and then treat when pod damage is first evident. This allows for most of the egg laying and hatching to occur before treatment. Economic thresholds have been developed for corn earworms and should be followed to ensure pesticide applications are necessary.

Stink Bugs

soybean pod. This invasive pest uses piercing-sucking mouthparts to feed on developing soybean pods. (Photo: Saratm, Adobe Stock)

Stink bugs (Figure 18) build up on many wild and cultivated host plants and typically invade soybean fields after pod formation in September. Over the past decade and a half, brown marmorated stink bugs have moved into the area, causing more problems than historically seen from native stink bug populations. Stink bugs tend to build up along field edges, especially near wooded areas or cornfields. Wheat harvest can also push stink bugs into neighboring soybean fields, where they can become a problem.

These green or brown shield-shaped bugs inflict mechanical injury with their piercing-sucking mouthparts, damaging young pods and seeds. Injured young pods often abort, while seeds in older pods may be discolored, malformed, or aborted. A common sign of stink bug activity in soybean fields is the presence of green stems at harvest. This physiological response to stink bug feeding can cause stems to senesce more slowly, leading to harvesting challenges. Brown stink bugs can be confused with predatory stink bugs, so proper identification is key to ensuring appropriate management. More information on stink bug identification can be found in the Field Guide to Stink Bugs of Agricultural Importance in the Upper Southern Region and Mid-Atlantic States.

V. Other Pests

Spider Mites

Spider mites (Figure 19), mainly the two-spotted spider mite, are very small (1/200 inch or 0.05mm) eight-legged arthropods, more closely related to spiders than to insects. Adult and immature mites are oval and pale yellow to green, usually with two or four black dorsal spots. Eggs are spherical, minute, and transparent to yellowish-green. Spider mites are dispersed passively by wind or actively crawl from adjacent weed or cultivated crop hosts into soybean fields. After females settle on a suitable plant, they begin to feed and lay eggs within a few hours. The life cycle is completed in 7 to 14 days depending on the temperature. As the population increases, young females disperse from infested plants by producing fine webbing, which serves as a bridge between adjacent plants and allows individuals to be blown more easily by the wind. Numerous generations occur each year in the Mid-Atlantic area.

Spider mites use their needle-like mouthparts to pierce individual tissue cells on the undersides of soybean leaves. They extract the entire content, leaving empty and irreversibly damaged cells. Numerous empty cells result in the yellow or white stipples that are characteristic of mite-injured leaves (Figure 20). This stippling injury is first noticed at the base of the leaf when 20 to 30 mites are present on the underside. Extensive feeding by large numbers of mites (300 to 600 per leaf) causes the leaves to turn yellow or brown on the margins and eventually die and drop from the plant. Yield losses begin when 50 percent of plants show stippling, yellowing, or defoliation affecting more than one-third of the leaf. Mite outbreaks usually are associated with hot, dry weather, which accelerates reproduction and development. During periods of high humidity and field moisture, fungal disease can reduce populations,but high temperatures can nullify these effects. Insecticide applications that kill natural enemies also contribute to outbreaks.

Check weekly for mites, starting in early July through August, especially during a hot, dry season. Concentrate on the field borders and look for the early signs of white stippling at the base of the leaves. Do not confuse mite damage with dry weather injury, mineral deficiencies, and herbicide injury. If feeding injury is evident, press the underside of a few damaged leaves on white paper to reveal any crushed mites. Determine the extent of the infestation and assess the level of injury by examining 20 to 30 plants in the infested area. Field infestations often show defoliated or injured plants at some localized point, with injury becoming less evident and extending in a widening arc into the field. Spot treat with miticides if these isolated infestations are confined to field edges.

Dectes Stem Borer

The dectes stem borer adult (Figure 21) is a dark gray, elongated beetle, about 5/8 inch (15mm) long, and has slender antennae that are longer than its body with alternating grey and back striping on them. Adults are often referred to as longhorn beetles due to their large antennae. This insect infests wild host plants such as ragweed and cocklebur but occasionally attacks soybeans in Mid-Atlantic area. The creamy, white legless larvae are about ½ inch (12mm) when fully grown. They tunnel into the main stem and eat the pith as they move down, leaving the cavity packed with excrement. Older larvae girdle the plant stem from the inside, causing it to break off at the girdled point, usually near the ground (Figure 22). Damage done by the dectes stem borer often leads to plants lodging and harvest losses associated with it. More information can be found in the University of Maryland Extension publication Dectes Stem Borer Management in Soybeans (FS-1196).

Thrips

Flower and soybean thrips (Figure 23) are yellow or yellowish brown to amber, about 1/16 inch (1.5mm) long, and have two pairs of long, narrow wings fringed with long hairs. They are often one of the most abundant insects in soybean fields but cause relatively little economic damage. All life stages feed on the undersides of the leaves, causing small silvery streaks and whitish or yellowish discoloration. Early season injury to drought-stressed plants can lead to reduced yields.

Potato Leafhopper

The potato leafhopper (Figure 24) is a common pest of forage legumes, beans, and other vegetables. It also attacks soybeans but rarely reaches population levels that affect yields. Leafhoppers overwinter in the Gulf States and move into the Mid-Atlantic area in late spring. Adults are highly mobile, spindleshaped, yellow-green, and about 1/4 inch (3mm) long. Several nymphal stages exist, each of which is wingless, which are smaller versions of the adults and are also very nimble. Nymphs and adults use their piercing-sucking mouthparts to feed on plant sap from the undersides of leaves. While feeding, they also inject a toxic substance, which interferes with normal plant growth. The symptoms of leafhopper injury, called hopper burn, include localized stippling, curling, and yellowing of leaf margins. Varieties are available that show resistance due to densely pubescent hairs on the stem and petiole. The presence and population levels of leafhoppers can be determined by using a sweep net.

Slugs

Slugs (Figure 25) can be a frequent pest in no-till and high-residue farming systems, particularly in fields with cover crops or heavy organic matter. Thriving in cool, moist environments, they can cause significant damage to soybean seedlings by feeding on cotyledons, leaves, and stems, killing young Unlike some insect pests, slugs do not currently have defined economic thresholds, making preventative management crucial. Damage is characterized by irregular holes in leaves, shredded cotyledons, and slimy trails on plants and soil. Unlike cutworms, slugs do not cut plants at the base but may severely damage the growing point, leading to plant death. Injury is most severe in cool, wet springs when slow seedling growth gives slugs more time to feed.

No-till fields with high residue are typically at greater risk, particularly in wet years. Preventative strategies such as residue management, proper cover crop termination, and planting adjustments can help mitigate slug damage. Proper furrow closure and the removal of residue above furrows help prevent slugs from accessing seeds and young plants before they emerge from the soil. Slug eggs (Figure 26) may also be present in these environments, often found clustered near the crown and roots of plants. These gelatinous, translucent eggs are typically located in moist soil or decaying plant matter, highlighting the importance of field scouting and residue awareness. More information can be found in the University of Maryland Extension publication Managing Slugs in Field Crops Using IPM Principles (FS-2022-0629).

Conclusion

Understanding and being able to identify the pests affecting soybeans in Maryland is an essential step toward making informed and effective IPM decisions. This publication is intended as a reference guide to help identify and understand key insect pests found in the region. While not all pests will reach economic injury levels each season, regular scouting and the use of IPM practices can help minimize yield loss and reduce overall pesticide use. Use this guide alongside your field scouting efforts to recognize pest activity and determine whether treatment is necessary.

Additional Resources from the University of Maryland Extension

Igwe, P., Cramer, M., Owens, D., Dively, G., & Hamby, K. (2023). Managing Slugs in Field Crops Using IPM Principles (FS-2022-0629)

Hamby, K., Leslie, A., & Owens, D. (2022). Dectes Stem Borer Management in Soybeans (FS-1196)

Kness, A. (2024). General Recommendations for Managing Nematodes in Field Crops (FS-1082)

Works Consulted

Bethke, J., Dreistadt, S., & Varela, L. (2014). Integrated pest management for home gardeners and landscape professionals: Thrips (Pest Notes Publication 7429). University of California Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program. https://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn7429. html?src=302-www&fr=4564

Dively, G. (1986). Soybean insect pests I (PMA- 14). University of Maryland Cooperative Extension Service.

Dively, G. (1986). Soybean insect pests II (PMA- 15). University of Maryland Cooperative Extension Service.

Douglas, M., & Tooker, J. (2012). Slug (Mollusca: Agriolimacidae, Arionidae) ecology and management in no till field crops, with an emphasis on the Mid Atlantic region. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 3(1), C1–C9. https://doi.org/10.1603/IPM11023

Hamby, K., Leslie, A., & Owens, D. (2022). Dectes stem borer management in soybeans (FS-1196). University of Maryland Extension. https://extension.umd.edu/resource/dectes-stemborer- management-soybeans-fs-1196/

Herbert, A., Malone, S., Dively, G., Greene, J., Tooker, J., Whalen, J., & Youngman, R. (2012). Mid-Atlantic guide to the insect pests and beneficials of corn, soybean, and small grains. Virginia Cooperative Extension. https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/dam/pubs_ext_vt_edu/444/444-360/ENTO-575.pdf

Igwe, P.-G., Cramer, M., Owens, D., Dively, G., & Hamby, K. (2022). Managing slugs in field crops using IPM principles (FS-2022-0629). University of Maryland Extension. https://extension.umd.edu/resource/managing-slugsfield-crops-using-ipm-principles-fs-2022-0629/

Kness, A. (2019). General recommendations for managing nematodes in field crops (FS-1082). University of Maryland Extension. https://extension.umd.edu/resource/generalrecommendations- managing-nematodes-field-crops-fs-1082/

Koch, R., Pezzini, D., Michel, A., & Hunt, T. (2017). Identification, biology, impacts and management of stink bugs (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) of soybean and corn in the midwestern United States. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 8(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmx004

Leskey, T., Herbert, D., Khrimian, A., Koch, R., Kuhar, T., Malone, S., Nielsen, A. L., & Whalen, J. (2012). Field guide to stink bugs of agricultural importance in the Upper Southern Region and Mid-Atlantic States (2nd ed.). USDA Agricultural Research Service. https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/30842/Field%20Guide%20to%20Stink%20Bugs.pdf

Lopez, L., Kuhar, T., Taylor, S., & Sutton, K. (2021). Biology and management of brown marmorated stink bug in Mid-Atlantic soybean. Virginia Cooperative Extension. https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/pubs_ ext_vt_edu/en/ENTO/ENTO-450/ENTO-450.html

Mehl, H. (2024). Nematode management in field crops. Virginia Cooperative Extension. https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/dam/pubs_ext_vt_edu/spes/spes-15/SPES-531.pdf

Reisig, D. (n.d.). Kudzu bug. NC State Extension Publications. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/kudzu-bug

Reisig, D. (n.d.). Soybean aphid in soybean. NC State Extension Publications. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/soybean-aphid-in-soybean

Shanovich, H., Dean, A., Koch, R., & Hodgson, E. (2019). Biology and management of Japanese beetle (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in corn and soybean. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 10(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmz009

Swenson, S., Prischmann-Voldseth, D., & Musser, F. (2013). Corn earworms (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) as pests of soybean. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 4(2), D1–D8. https://doi.org/10.1603/IPM13008

Thekke-Veetil, T., Lagos-Kutz, D., McCoppin, N., Hartman, G., Ju, H., Lim, H.., & Domier, L. (2020). Soybean thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) harbor highly diverse populations of arthropod, fungal and plant viruses. Viruses, 12(12), 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12121376

Tooker, J., Wallace, J., Esker, P., & Collins, A. (2021). An IPM program for soybeans in Pennsylvania. Penn State Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/ipm-program-for-soybean-in-pennsylvania-a-comprehensive-approach-to-controlling-invertebrate-pests-weeds-and-diseases

Welty, C., Jasinski, J., & Tilmon, K. (n.d.). Brown marmorated stink bug (ENT-90). Ohio State University Extension. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/ent-90

HAYDEN SCHUG

hschug@umd.edu

GALEN DIVELY II

galen@umd.edu

This publication, Common Soybean Pests in Maryland (FS-2025-0759), is a part of a collection produced by the University of Maryland Extension within the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

The information presented has met UME peer-review standards, including internal and external technical review. For help accessing this or any UME publication contact: itaccessibility@umd.edu

For more information on this and other topics, visit the University of Maryland Extension website at extension.umd.edu

University programs, activities, and facilities are available to all without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, marital status, age, national origin, political affiliation, physical or mental disability, religion, protected veteran status, genetic information, personal appearance, or any other legally protected class.

When citing this publication, please use the suggested format:

Schug, H., & Dively II, G. (2025). Common Soybean Pests in Maryland (FS-2025-0759). University of Maryland Extension. go.umd.edu/FS-2025-0759