II. Enterprise Selection

Formulate a Farm Strategy

Section Authors:

- Ben Beale, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension-St. Mary’s County

- Shannon Dill, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension-Talbot County

- Neith Little, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension-Urban Agriculture

Setting goals and developing an overall farm strategy will be a way to focus ideas, conduct market research and create an overall plan.

Goal Setting

Prior to formulating a farm strategy it is helpful to think about the overall goals of the farm from a personal and business perspective. What are the reasons why you want to farm and what are your business expectations? Having these goals in mind will be important as you go through the steps of developing a farm strategy.

- I want to farm because:

- I have the following personal and family goals:

- I have the following farm goals:

- My timeline to collect resources and start the farm operation is:

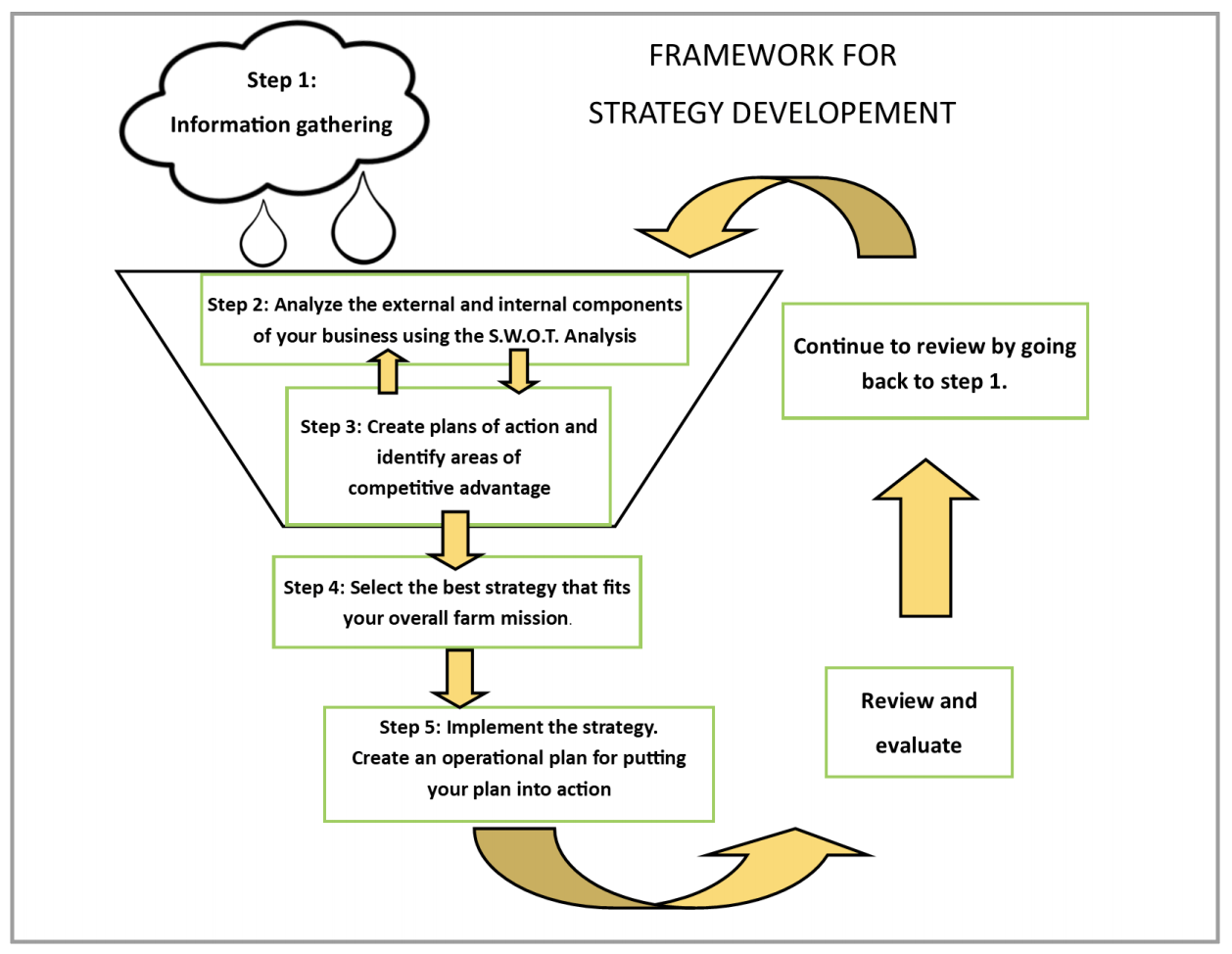

Developing a farm strategy is a series of steps:

With your goals in mind, now it is time to develop a farm strategy that will help you reach those goals. This Guidebook outlines 5 steps to developing a farm strategy.

- Gathering information and market research

- Analyzing the external and internal components of your business using the S.W.O.T. analysis

- Creating plans of action and identifying areas of competitive advantage

- Selecting the best plan that fits your overall farm mission

- Implementing and evaluating the strategy

Step 1: Information gathering and market research

This step considers what, why, and how the customer wants a product or service.

Market Research: Research current and potential markets to identify trends, competitors, needs, and buyers. Be sure to take time to collect data. Obtaining good data serves as the foundation for the creation of an effective strategy. The better the information, the better your strategic plan will be. For example, if you are considering raising pastured pork, you will need to research whether pastured pork is currently available in your area, how much it sells for currently, how many potential customers eat pork, how much they value pastured pork over other pork options, etc.

Never rely only on your opinion of what the market wants. There are a number of tools that you should consider using for your research:

Networking: A one-on-one interview can be helpful for generating ideas. Interview other business owners or operators who may be able to provide good information on what has or has not worked for them. Talk with similar farms and producers. Attend tradeshows, conferences, and business functions to meet other entrepreneurs, talk, and network about market trends. Sales representatives are also good sources of information.

Demographics: Information about the consumer in your area can be very helpful in marketing to them. The U.S. Census is a great place to find this information.

Observation: Simply taking time to observe can be a powerful tool. What are people buying? What are competitors offering?

Surveys: Surveys can be written or oral. A written survey can be distributed to a wide range of the population. Consider using an incentive to increase survey response rate, such as free products or coupons.

Focus Groups: A small group of potential consumers who are asked specific questions about the product/service.

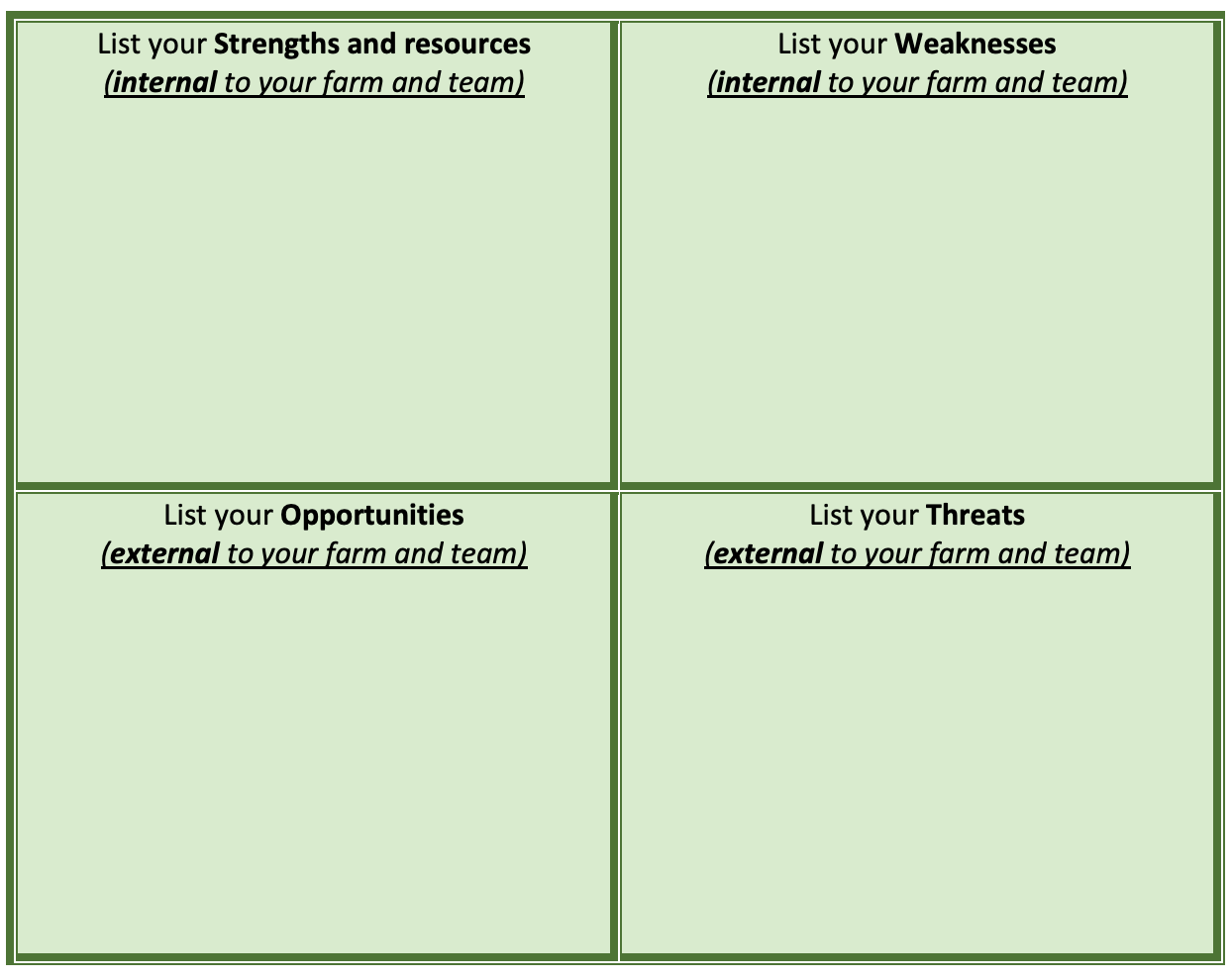

Step 2: S.W.O.T. analysis

The S.W.O.T. analysis is an analytical tool used to collect information and guide the decision making process in order to obtain strategic advantages.

Strengths and Weaknesses -Evaluation of the Internal Environment

The strengths and weaknesses section is internal to the organization and provides insight into what components are available to provide for competitive advantages. Filling out this section allows the organization to identify the resources available and acknowledge the gaps that will need to be filled.

Examples include: operations, equipment, facilities, knowledge, finances, technology, and experience.

Opportunities and Threats—Evaluation of the External Environment

This part of the S.W.O.T. analysis focuses upon the external opportunities and threats that exist. The analysis allows the organization to identify strategies that take advantage of opportunities for growth while avoiding potential threats.

Opportunities and threats are external to the organization and thus cannot be changed by the organization. Rather the organization must change with and react to the changing external factors.

Examples of opportunities and threats include new markets, expanding markets, government regulations or incentives, new technology, increasing competition, lower or higher barriers to entry, or economic conditions.

S.W.O.T. Analysis

Step 3: Creating plans of action and identifying areas of competitive advantage

As you think through the strategic planning process, do not try to come up with the ultimate best strategy for your operation right from the start. You will need to consider all of the possible strategies you could employ based on the findings from the information discovery and S.W.O.T. analysis. Compare and contrast the competitive advantages each strategy may offer and select the best after you review all of the areas of competitive advantage. This should be an ongoing, creative process. If you find this phase difficult, break apart the process and start with information discovery first, followed by focusing on the marketing strategy phase.

Things to think about when developing a plan of action:

Businesses will create competitive strategies to set themselves apart from others in the market. Types of competitive strategies can include least-cost and differentiation.

- Least-cost strategy focuses primarily on the price or cost of the product. Being the least expensive in the market gains the product competitive advantage. This strategy is known for cutting input costs and often the product is a “no frills” product. This type of strategy is normally focused on efficiency of operations. Most commodity-based industries such as the grain industry utilize a best or least-cost strategy. Generally small farms lack economies of scale and will not want to compete in a commodity market based solely on price. Instead, you will want to compete based on some unique or differing attribute that offers the customer perceived value.

- A differentiation strategy distinguishes the differences of a product to make it more desirable to a specific market. The strategy focuses on goods and services needed to satisfy the customer where the value outweighs the increased cost. A differentiation strategy also sets your product apart from the competition, creating a competitive advantage by offering a unique or different product or service that other companies either cannot or will not offer.

The questions below will provide some tips for outlining a differentiation strategy including your product, attributes, and pricing:

- What is unique or different about your farm business (products and/or services)? Unique attributes may include: production methods, packaging, location, availability, etc.

- What is the competitive advantage garnered from your strategy?

- The product/service attributes should be unique enough that other competitors cannot easily copy it, but adequate enough to capture a sustainable market share.

Step 4: Selecting the best plan that fits your overall farm mission

It is now time to review the previous steps 1-3 and select the plan that best fits your overall farm business. Keep in mind your business’s strengths and weaknesses as well as external opportunities and threats. Once all of the possibilities have been laid out and the best strategy chosen, be sure it fits with your farm mission and objectives. Can you see yourself doing this in 5-10 years?

The overall strategy is derived from component strategies including marketing strategy, production/operational strategy, financial strategy, and management strategy. Be sure to include the main components of marketing, production, finances, management, and your key competitive advantage points.

Step 5: Implementing and evaluating the strategy

You have done your homework, conducted market research, and developed areas of competitive advantage. The implementation plan will contain a timeline for the steps needed to meet business objectives. Consider the implementation plan your ultimate “To-Do List”. The timeline will cover the production, financial, management and marketing goals outlined in the business plan. As you develop an implementation plan, you may begin to notice areas where the best-made plans are not practical. Taking time to go through this process will help you identify bottlenecks and avoid pitfalls. Be sure to continue to evaluate your farm strategy as goals, markets and other situations change.

Organic Production and Certification

Section Authors:

- Ben Beale, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension-St. Mary’s County

- Shannon Dill, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension-Talbot County

- Neith Little, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension-Urban Agriculture

Organic produce has become very popular in the last 10 years. Growing vegetables organically requires physical input and critical thinking when approaching pest and fertility management. Organic production is a ‘system’ approach. Crop nutrients and soil fertility are managed through rotations, use of cover crops, and application of plant and animal materials. Pests are managed through the increase in biodiversity of the system, encouraging natural enemies, and the use of products that are approved by the National Organic Program (USDA). Weeds are managed through the use of mulches, tillage, and hand labor. Few chemical weed suppression products are effective.

Organic Production Methods

Soil productivity and health are the cornerstones to healthy plants that can withstand attacks from pests and diseases. Soil organic matter, which can be enhanced through the use of cover crops, composts and natural mulches, can serve as a reservoir of plant nutrients, enhance soil biological diversity and improve soil tilth, structure, and water holding capacity. The proper use of crop rotation in an organic system allows cover crops to be utilized in the most effective manner by breaking the disease cycle, increasing soil organic matter, increasing biodiversity, encouraging beneficial insect populations, and providing a nitrogen source to the crops that will be grown.

Soil testing is necessary to determine crop needs. Soil tests will indicate recommended rates of phosphorus and potassium required for crop production (University of Maryland Extension Publication EB-236). Organic producers can provide nutrients to their crops through the use of composted manures, cover crops, and approved blended materials. Blended fertilizers must be approved by the NOP (National Organic Program).

Organic growers are required to improve the biological productivity of their soil, and one way they achieve this is through the use of cover crops. These cover crops, while providing organic matter and erosion control, can also provide nutrients, many in the source of nitrogen. It is difficult to determine the actual quantity of nitrogen each cover crop can provide to the subsequent cash crop, as growth rate and biomass will be variable at maturity.

To control weeds vegetables are often grown on black plastic with trickle tape that will supply the plant’s water needs. Organic growers often use other mulches that are readily available (straw, newspaper, or planting directly into a killed cover crop). In all organic production systems, weeds must be controlled because they are the number one cause of yield loss, as well as the most difficult pest to manage. Supplemental weed management is obtained through the use of cover crops, tillage, flaming, and manual removal. The manual control of weeds in an organic system is one of the factors that increase the cost of raising vegetables organically. Seasonal labor sources must be secured in order to maintain the productivity of the crop.

Insects are managed through enhancement of biodiversity (increasing natural enemy populations, providing habitat, elimination of non-selective chemical controls), crop rotation, adjusting planting dates, and the use of approved chemical products.

Pricing and Marketing Organic Products

For many traditional agricultural products, profit margins can be minimal. But, organic certification offers a premium that consumers may be willing to pay for the organic label. (The premium includes the cost of products grown organically above the cost of conventionally grown products, as well as increasing demand for organic products.) Organic production is more labor intensive and prices should reflect that cost. Pricing directly affects profit margins and will depend upon the market outlet, market position, target consumer, cost of production, and local prices.

Common sales channels for organic products include direct marketing. Direct marketing refers to sales of a good or service from the producer directly to the consumer, through market outlets such as farmers’ markets, roadside stands, and CSAs. This eliminates wholesale marketing and the middleman and sells directly to the consumer. There is an increasing organic wholesale market to health stores and supermarkets due to consumer demand. Selling to these larger markets often takes higher quantity of production, and may pay lower prices than can be achieved in direct market outlets. Organic wholesale markets are still somewhat immature, but are growing. According to the Organic Trade Association, organic products are available in 73 percent of conventional United States grocery stores and consumers continue to demand more.

Identifying your target customer is an important step in developing a marketing plan. There are consumer segments that demand, search for, and purchase organic products. This is generally a health conscious consumer who wants to buy fresh and local products. This may be a consumer with more disposable income who is willing to pay more for organic products.

The Organic Certification Process

USDA Organic is a national certification for farmers who use organic practices. To use the USDA Organic label, a grower must become

Certified Organic, and maintain that certification from year to year. Farms and other businesses who have an organic certification are listed in a public USDA database.

An exemption to the certification requirement is available for very small-scale growers who have less than $5,000 in organic sales annually and follow organic practices as defined by the USDA's National Organic Program Rules. Exempt producers are allowed to describe their products as organic, but are not allowed to use the USDA Organic label. The Maryland Department of Agriculture offers a registration program that allows exempt organic producers to be listed in state and federal organic directories.

To become Certified Organic, a farmer will need to understand the National Organic Program rules, develop a plan for how they will follow those rules, and submit an application to a third-party certifier who will review the plan and inspect the farm. This process may take three years, if the land being certified has previously been used for conventional agricultural production. A variety of third-party certifiers exist, including the Maryland Department of Agriculture.

A more detailed description of the organic certification process is available in the Maryland Organic Production Manual.

Other Related Certifications

Several other certifications of farming practices exist focused on sustainability and humane treatment of livestock. Certified Naturally Grown is a grower-run program where farmers review each other’s’ production practices. “Certified Humane” and “Animal Welfare Approved” are two third-party certifications of livestock production practices.

Additional resources

If you want to use organic practices and are interested in marketing what you produce as organic, you will need to begin learning more and planning your organic farming practices and record-keeping system. The following resources will help you start on this journey.

Understanding Farm Equipment Needs

Section Author:

- Ben Beale, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension - St. Mary's County

Every farm operation relies upon tools to help get the job done-some enterprises are able to remain competitive with a minimal investment in equipment, while others require substantial investment. Equipment, along with land, is typically a major cost driver for farm operations. It is thus important to critically evaluate the need for each piece of equipment before buying. Visiting similar farm operations to see equipment working, talking with you farm equipment sales representative about equipment options, attending trade-shows and farm demonstrations are all a good way to learn which equipment might be best suited to your farm. A visit to your local Extension office or Soil Conservation District is also a good place to start to learn what others in the region are using and local sources for equipment.

Frequently asked questions regarding farm equipment

What are the best sources for farm equipment?

- Farm equipment is most often purchased from local dealers, farm auctions, directly from other farmers, and through internet listings. A good source of information on equipment availability in Maryland is the Delmarva Farmer Newspaper Classified section, or the Lancaster Farming Newspaper Classified section.

Can I rent or lease equipment to get started?

- Yes-many counties or regions offer farm equipment for rent on a daily or per acre basis. Commonly available equipment includes no-till drills and conservation planters. The Southern Maryland Agricultural Development Commission has compiled a listing of equipment available for rent.

What is a custom farm operator and how do I use them?

- Many farm tasks can be completed by custom operators. In other words, hiring another firm to complete certain tasks, such as spreading lime, hauling goods, planting grain, fumigation or harvesting grain, to name a few. University of Maryland has developed a Custom Equipment Average Work Charges factsheet. The factsheet will give you an average per acre charge for a particular farm task. The availability of custom operators varies greatly from county to county. Ask a fellow farmer or farm agency for help in identifying custom farm operators. Also be aware that custom operators may decline or charge more for small acreage jobs.

What kind of equipment do I need for my farm?

- Equipment needs vary tremendously between enterprises. A listing of different enterprises with an accompanying chart of commonly utilized equipment with prices is available here.

Avoiding the top 5 common equipment pitfalls

- Buying equipment that the farm will never be able to pay for. Modern farm equipment is expensive. New farmers often make the mistake of purchasing more equipment than they need for the size operation they have. For example, a modern grain operation will incur equipment of costs ¾ of a million dollars. This large cost typically requires that the investment be spread among many acres (1,200-1,500) to be economically feasible. Knowing your economy of scale and sizing the equipment to fit that scale is a critical first step. This is true whether you are farming 3 acres or 5,000.

- Buying equipment the farm doesn't need. This one is pretty self-explanatory. It can be tempting to buy that shiny tractor at a farm auction when you don’t have a real need. Do your homework first, and remember that the bill still comes due whether you use the equipment or not.

- Improperly sizing equipment for the job at hand. Be sure the power source, implement, and the task at hand are compatible with each other. In other words, don’t hook a 6 bottom plow to a 40 horsepower tractor to till a ¼ acre vegetable plot.

- Buying all new equipment. Both new and used equipment has a fit. Used equipment can lower initial fixed costs, and allows a beginning farmer with a lower economy of scale to justify an equipment purchase. Used equipment does require the operator to have some mechanical aptitude.

- Buying equipment and never learning how to use it properly. Take time to read the operator's manual, listen to others and request a set-up demo from the seller to learn how to properly operate a piece of equipment.

Cost of Equipment

When developing a cost analysis for a new enterprise of farm, consider the true cost of the equipment. These costs are often referred to as the DIRTI-5:

- Depreciation

- Interest

- Repairs

- Taxes

- Insurance

The initial price of a piece of equipment will provide you with an estimated impact to cash flow-when and how much the monthly payment will be for example. However, a more accurate picture of the true cost of the equipment can be obtained by spreading the cost out over the useful life of equipment. For example, a tractor may have an initial cost of $30,000. If the tractor has a useful life of 10 years and a resale value after 10 years of use of $10,000, then the true depreciation cost would be $2,000 per year. Add in interest, repairs, taxes, and insurance, and the true cost will more likely be $3,000 to $4,000 per year, plus operating expenses (fuel, oil, maintenance) of around $10 per operating hour.

Grain Farm

Grain Farm Assumptions: The following equipment is based upon a 1,500-2,000 acre operation with limited storage. Equipment cost estimates are based on new or near new condition equipment. The sample operation follows a standard rotation of small grain (wheat/barley), full season soybeans, corn and double crop soybeans or sorghum. Most field operations are completed no-till or reduced till, which minimizes the amount of tillage required. Some custom work is utilized for hauling grain to the elevator, fertilizer application and some field spraying.

| Field Equipment | Description | Average costs for new or near new condition |

|---|---|---|

| Tractor Over 150HP | Cab, 4wd, GPS | $110,000.00 |

| Tractor Under 150HP | Cab, 4wd, GPS | $75,000.00 |

| Tractor, Utility, 50-75 | Open Platform, 2wd, utility | $35,000.00 |

| Combine | Mid-large capacity | $250,000.00 |

| Pick Up Truck | 3/4 ton | $40,000.00 |

| Disc | 20 ft. used | $18,000.00 |

| Chisel Plow | 12 ft. used | $15,000.00 |

| Cultivator, field | 20 ft. used | $12,000.00 |

| Grain Drill | 15 ft., no-till equipped | $50,000.00 |

| Planter (corn/bean) | 8 row, no-till equipped | $70,000.00 |

| Combine Corn Head | 6 row | $42,000.00 |

| Combine Grain Head | 18-25 ft. platform | $35,000.00 |

| Sprayer-boom type | 60-90 ft. boom. Pull type | $45,000.00 |

| Mower | 10 ft., Heavy Duty |

$5,000.00 |

| Transportation/Storage | ||

| Grain Wagon | 600-800 bushel | $12,000.00 |

| Grain Truck | Straight Truck, Single Axle | $25,000.00 |

| Buildings | ||

| Pole Building | Equipment storage | $25,000.00 |

| Total | $767,000.00 | |

Hay Operation

Cash Hay Assumptions: are based on small square bales, utilizing a pull type stack wagon for up to 200 acres. For smaller operations, eliminate stack wagon and increase hay wagons. Smaller operations (1-75 acres) may also consider eliminating one tractor, drill and boom sprayer. Equipment cost estimates based on new or near new condition.

| Field Equipment | Description | Average new or near new condition |

|---|---|---|

| Tractor 60-80HP | 2 or 4wd, Diesel, Cab | $38,000.00 |

| Tractor 40-50HP | 2 wd, diesel, no cab | $30,000.00 |

| Mower Conditioner | Disc type, 10-12 ft. model | $18,000.00 |

| Rake | Wheel type, 12-15 ft. model | $8,000.00 |

| Tedder | 9-12 ft. | $6,500.00 |

| Baler; Small Square | Mid-size, 540 PTO, Preservative Applicator | $23,000.00 |

| Hay Drill (used) | No-till, 10 ft. | $8,000.00 |

| Stack Wagon | Pull-type | $35,000.00 |

| Boom Sprayer, 3-500 gal. | 45-60 ft. boom | $10,000.00 |

| Transportation/Storage | ||

| Pick Up (used) | 3/4 Ton | $20,000.00 |

| 2 Hay Wagons | $10,000.00 | |

| Buildings | ||

| 2 Pole Buildings | High clearance for stack wagon | $40,000.00 |

| Total | $246,500.00 | |

Example of Typical Equipment Required and Cost for a Small 5-15 Acre Vegetable Farm

| Field Equipment | Description | Average Used Cost | Average New Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tractor -general | 55 hp, diesel | $12,000.00 | $30,000.00 |

| Disc Harrow | 9 foot- transport | $1,800.00 | $3,600.00 |

| Field Cultivator | Perfecta II-8 ft. | $3,000.00 | $4,000.00 |

| Cultipacker | 8 ft, non-transport | $500.00 | $1,200.00 |

| Rotary Mower | 5 ft. | $500.00 | $1,000.00 |

| Tractor-Cultivator | Farmall C, 30HP, 2 row. New model is 30 hp modern cultivating. | $4,000.00 | $22,000.00 |

| Attachment Sweeps | 1 set sweeps, 1 set finger discs | $1,000.00 | $1,200.00 |

| Vegetable Transplanter | Mechanical, 1 row, with water attachment | $1,500.00 | $2,000.00 |

| 2 row precision direct seeder | Monosem, vacuum, addl. plates | $4,000.00 | $6,500.00 |

| 8 ft drill | Conventional, 7 inch row spacing | $2,000.00 | $8,000.00 |

| Raised Bed Mulch Layer | 4 ft, drip attachment, 8-10 inch bed | $2,000.00 | $4,200.00 |

| Water wheel transplanter | 1 row, 3 pt hitch, water attachment | $1,100.00 | $1,600.00 |

| Wagon | 4-wheel, 18 ft | $2,000.00 | $2,600.00 |

| Wagon | 4-wheel, 18ft | $2,000.00 | $2,600.00 |

| 100 Harvestings lugs | Plastic, perforated with handles | $300.00 | $500.00 |

| Packing Line | 16 inch, 4 unit packing line with rotary packing table | $2,000.00 | $3,000.00 |

| Total | $39,700.00 | $94,000.00 |

Food Safety Overview

Section Author:

- Shauna Henley, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension-Northern Cluster

Food safety is no longer what you learned from your family elders, but rather an emerging expectation from your future buyers - safe, nutritious, and unadulterated foods. As a beginning farmer, food safety must be part of your farm’s fabrication, while you grow and evolve the food safety culture of your operation. Staying up-to-date on the regulations and the science is your responsibility. The following will provide a broad introduction of the regulations, certifications, and resources in Maryland for food safety on your farm.

Quick overview of the Regulation Hierarchy:

It is important to have a basic understanding of the organization of regulatory agencies and jurisdictions around the food system. At the top are federal level agencies created by Congress to regulate and enforce federal laws. The USDA (1862), FDA (1906), and EPA (1970), and each play a role in regulating some part of the food supply chain (e.g. organic certification, interstate commerce, microbial standards, waste water disposal). Underneath the federal agencies are state jurisdictions, that are regulated in Maryland by the Maryland Department of Agriculture (MDA), Maryland Department of Health (MDH), and Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE). Underneath the state departments are local county government’s Environmental Health Services (EHS) department.

Typically at the federal level, it is expected that scientifically-based minimal standards for food safety are met, while state and county governments can choose to make more stringent regulations than what was federally introduced.

Certifications for Produce

Good Agricultural Practices & Good Handling Practices (GAP/GHP)

GAP/GHP was established in 1999, and is a voluntary audit for those growing produce (fruits and vegetables) and either pack, handle (post-harvest), and/or store produce. While it is voluntary, many buyers will require GAP certification from growers they purchase produce from. The goal of the audit is to help producers reduce and/or eliminate microbial contamination risks to prevent consumers from eating contaminated fresh produce. Growers should know whether or not buyers expect their farm operation to be GAP certified, as part of the buyer's food safety protocol.

The areas of focus to prevent microbial contamination during a GAP/GHP training are:

- Worker health and hygiene

- Water quality and safety

- Soil amendments - manure and compost use

- Animals - Domestic, wild, and livestock

GAP/GHP in Maryland

The Maryland Department of Agriculture (MDA), Food Quality Assurance Program, in collaboration with the University of Maryland host grower GAP/GHP training statewide for a nominal fee. Participants who complete the training will receive a certificate of completion, however, an operation will still require a food safety plan and an audit to be in full compliance.

The MDA Food Quality Assurance Program will perform the GAP/GHP audits. A grower will need to request an audit, and know the audit inspection questions in advance. There are other types of GAP/GHP are available, including: Mushroom GAP, Group GAP, Harmonized GAP and Aquaponics GAP (Pilot).

Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA): Produce Safety Rule (PSR)

The Produce Safety Rule is a federally regulated standard for production, harvest, handling, packing, and holding of fruits and vegetables for human consumption. Unlike the voluntary nature of a GAP/GHP audit, the FSMA Produce Safety Rule establishes a mandatory legal obligation, for the farms subject to the rule, to follow certain food safety requirements.

According to the Produce Safety Rule, it is required that “at least one supervisor or responsible party for your farm must have successfully completed food safety training at least equivalent to that received under standardized curriculum recognized as adequate by the Food and Drug Administration.” The curricula typically used is from the Produce Safety Alliance.

Who must comply with FSMA Produce Safety Rule?

Farming operations may be considered Covered (must comply with the PSR), Qualified Exempt (modified compliance), or Exempt (from the rule and complying). Farming operations that must comply with the Produce Safety Rule will vary, based on farm activities (which crops are grown and where they are send) and revenue. Farming operations that grow certain commodities that are NOT covered by the rule are Exempt from complying with the Produce Safety Rule. Operations that grow commodities that are covered by the PSR must calculate their 3-year average annual produce sales, with inflation adjustments, to determine if they are Covered or Qualified Exempt. For more on compliance visit the FDA website.

FSMA in Maryland

The Maryland Department of Agriculture (MDA), Food Quality Assurance Program, in collaboration with the University of Maryland host grower training statewide for a nominal fee. An all-day grower training will cover seven PSA curriculum modules. Participants who complete the training will receive a certificate of completion, however, an operation will need to implement various recordkeeping tasks to be in compliance. Due to the increased foodborne risk from consuming sprouts, special considerations have been made for farm operations that grow sprouts.

On Farm Readiness Review (OFRR)

As part of the FSMA Produce Safety Rule, farms may undergo a mock inspection. In order to prepare farm operations for an inspection, the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture Research Foundation (NASDA) is providing a confidential and free inspection, so farm operations are prepared for what a real inspection may look and feel like.

Livestock

If you are thinking of keeping animals for agricultural purposes, work with your local UME Agricultural Educator and MDA to ensure animal welfare best practices, and reduce any foodborne risks on your operation. Animals are known carriers of foodborne pathogens, and having a farm with mixed agriculture (produce and animals) will require more thought. Understand the various animal health programs through MDA, and other responsibilities that could relate to tagging, diseases, biosecurity, registration, etc.

Food Processing

Starting a food business will require a strong understanding of local, state, and possibly federal regulations. The foods you process and where the food is processed will play an important role in what food safety laws your business will need to follow. Information on the Maryland Rural Enterprise Development Center, as well as your country's small business development are a wealth of knowledge on this topic. Become knowledgeable about the Maryland Department of Health’s Office of Food Protection. Find information about how to meet state requirements for food processing, Cottage Foods, packaging, processing, and licensing your food product requires to meet state requirements.

Resources and Web Links - Enterprise Selection

Organic Certification Links

- Maryland Organic Production Manual

- UMD Commercial Vegetable Recommendations

- Maryland Organic Foods and Farming Association

- ATTRA – National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service – Organic Farming

- USDA / AMS National Organic Program

- SARE – Transitioning to Organic Production

- USDA Alternative Farming Systems Information Center: Organic Production

Handy Equipment Links

- Equipment Basics for a Small Farm

- University of Vermont video on “Vegetable Farmers and their Weed-Control Machines”

- University of Vermont video on “Farmers and their Innovative Cover Cropping Techniques”

- University of Vermont video on “Vegetable Farmers and their Sustainable Tillage Practices”

- Delmarva Farmer newspaper classified section

- Lancaster Farming newspaper classified section

- Vegetable Farming Equipment

Food Safety Links

- Extension Food Safety Page

- Maryland Department of Agriculture Food Quality Assurance

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration Standards for the Growing, Harvesting, Packing, and Holding of Produce for Human Consumption

- Food Safety Modernization Act Video

- USDA Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) & Good Handling Practices (GHP)

- GAPs Online Training

- FDA FSMA Rules & Guidance for Industry

- Maryland Department of Agriculture Who What and When FSMA Brochure

- FDA Standards for Produce Safety

Enterprise Selection Review - Questions to Ask Yourself

- Did you conduct a SWOT analysis of your enterprise selection? What are your internal strengths and weaknesses and external opportunities and threats?

- Have you defined your farm strategy and what is your competitive advantage?

- What type of farm equipment will your enterprise need? Estimated costs?

- Have you considered organic certification and understand the differences in growing and record keeping?

- Have you reviewed the food safety regulations and understand your responsibilities?

MD Beginning Farmer Guidebook home

Next: Business Planning

Previous: Farm Establishment