Autumn olive is a multi-stemmed deciduous shrub that is another example of the best intentions gone awry. This species was widely planted for erosion control and to provide wildlife habitat. It provided vegetation cover quickly and helped stabilize a variety of sites. However, autumn olive is now considered an invasive plant species for a variety of reasons. While it is not illegal to sell the plant in every jurisdiction where it exists, many natural resources management agencies and organizations discourage property owners from further planting.

What is it?

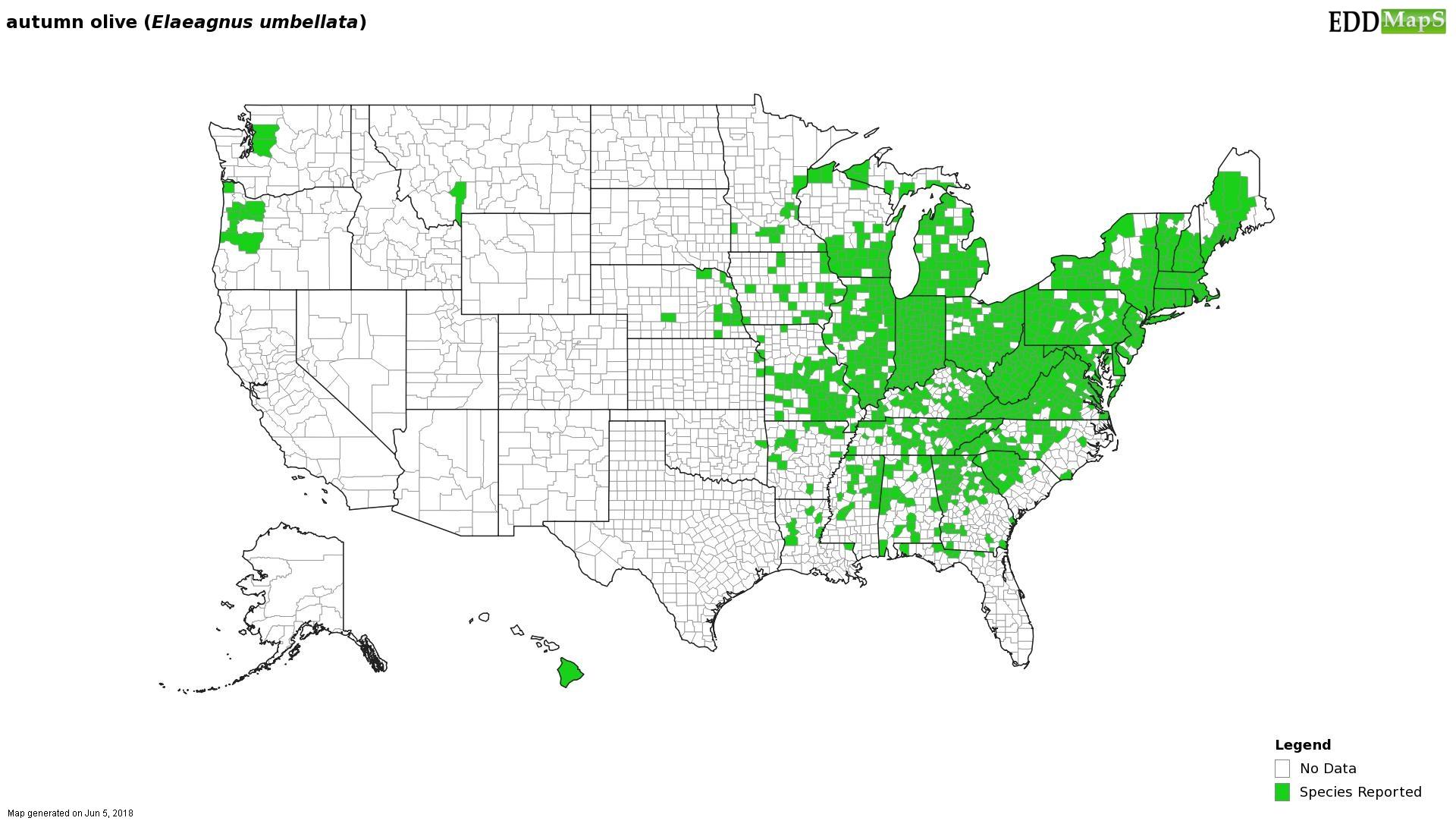

Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb.) is a native of Japan, China and Korea, and was first introduced to the United States as an ornamental plant in the 1830s. It is also called Elaeagnus, Oleaster, or Japanese silverberry. It remained in small numbers until the 1940s, when organizations began to plant them in revegetation projects of disturbed areas. These included railroad rights-of-way, utility rights-of-way, roadsides, disused strip mines and abandoned gravel pits. Autumn olive was chosen for many of these sites because of its nitrogen-fixing nodules that enable it to endure and even thrive in poor soil conditions. It also tolerates the effects of salt and drought. Consequently, autumn olive spreads rapidly into open spaces, including abandoned fields and early successional habitats. It out-competes and displaces native plants by creating dense shade conditions that hinders growth of plants that would normally grow in such full sun conditions. Today, it is found throughout most of the eastern U.S., as far west as Missouri in substantial numbers, and in other states further west in isolated communities. See the distribution map below.

How does it spread?

Autumn olive spreads rapidly through two main methods. The nitrogen-fixing nodules allow it to grow in even the most unfavorable soil conditions. Additionally, it can produce up to 200,000 seeds and eight pounds a year in fruit that birds find extremely tasty. The seeds are distributed far and wide as the birds consume the berries, fly away, and excrete the seeds.

How can I identify it?

Autumn olive is a multi-stemmed deciduous shrub that can grow as tall as 20 feet. The bark is olive drab and the branches contains many thorns. The shrub has waxy green leaves, elliptical in shape and alternate in arrangement, with silvery scales on the undersides. It blooms early in the spring with cream– to pale yellow-colored blossoms. The highly-abundant berries follow, which are pink to red and dotted with scales. The berries themselves are quite small—less than 1/4 an inch in size. See the Image Gallery below.

How can I control it?

Once established, autumn olive is often difficult to eradicate from a habitat without continued effort. Individual plants will re-sprout if mowed or cut; it will also re-sprout from the stump if it is burned. In fact, areas in which autumn olive has been cut, mowed or burned often encounter more abundant regrowth. There is also the chance that new growth will begin when seeds from adjacent areas arrive. Mechanical controls, such as pulling and digging, can be effective in removing small seedlings and sprouts. Take care to remove and bag all fruit if possible.

Chemical controls are the most effective means presently available for dealing with autumn olive. Using the cut stump method with an immediate application of glyphosate in a 20—50 % solution has proven effective in killing the roots and preventing re-sprouting. This method can be followed both late in the growing season (July to September) and in the dormant season. Foliar application can be effective as well; ensure complete coverage of the foliage and avoid spraying desirable vegetation.

For more information:

Learn more about autumn olive:

Autumn olive (Penn State Extension)

Autumn Olive: Your Invasive, Seedy Neighbor (The Nature Conservancy)

Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas: Autumn Olive (National Park Service & U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)