I. Farm Establishment

Considerations for Acquiring a Farm: Selecting the Best Farm Property

Section Authors:

- Ben Beale, Extension Educator, University of Maryland Extension

- Greg Bowen, Southern Maryland Agriculture Development Commission

- Paul Goeringer, Research Associate, Center for Agricultural and Natural Resource Policy

- Margaret Todd, Law Fellow, Agriculture Law Education Initiative

Disclaimer: The following is intended for educational purposes only and is not legal advice.

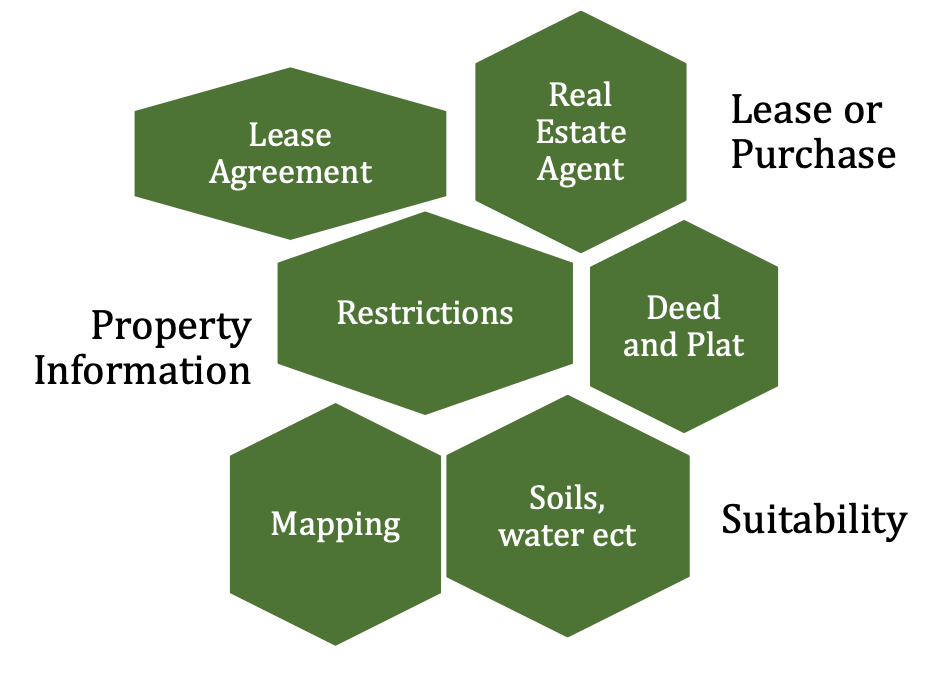

A successful farm operation requires thoughtful property selection, whether you are leasing or purchasing land. When looking at properties, you need to consider how the property will support the goals in your business plan. Will the farm be productive? Will the location and regulatory environment fit into your marketing strategies, or can you adjust your strategies to suit your income needs? Is the price of the farm reasonable and realistic given your financial goals? Are there any zoning, covenant, easement, or plat restrictions that might prevent you from producing or selling what you want, where you want?

Maryland farmers are fortunate to have strong regional market opportunities and many farms contain soil types that will grow a wide variety of crops. However, because Maryland has the fifth highest population density of any state in the nation and is divided by the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, Maryland has greater need to regulate land use for the health, safety, and welfare of its citizens than other rural states. Much of the land currently in agriculture is available because of zoning, covenants, easements, or plat restrictions that limit nonagricultural uses.

Lease or Purchase?

Many beginning farmers lack the financial resources to buy land, or they would rather invest in their farm business rather than tying up all their capital on land purchase. Land leasing is a viable option in Maryland. The majority of farmland is leased on a year-to-year basis for grain or forage production. A disadvantage of leasing is that it is difficult to secure leases long enough to be comfortable making major improvements to a farm. If you know what your long term business plan is and you can find a property that fulfills the needs, then land purchase may be the best option.

Several resources exist online to help beginning farmers understand leasing options and what to look for in leasing agreements. The University of Maryland Extension and Agriculture Law Education Initiative provides legal resources to help farmers looking to lease. Loan options for land or infrastructure purchase are available at the federal and state levels, including: USDA loans, the Farm Credit System, and Maryland Agricultural & Resource-Based Industry Development Corporation (MARBIDCO). Maryland FARMLink has a land link service that aims to connect those who want to sell or lease farmland with those who want to buy or lease.

Utilizing a Farm Real Estate Agent

When you begin the search for a farm property, consider utilizing the services of a quality farm real estate agent. A good agent will be knowledgeable on what to consider when purchasing farmland, will have an idea on what to expect during the transaction, and can make the process less stressful. An agent will serve on your behalf and will often be able to catch land caveats.

It is important to understand how a real estate agent is typically paid and who represents the buyer and seller. The Maryland Real Estate Commission (MREC) has prepared a document entitled “Understanding Whom Real Estate Agents Represent” that explains the roles of each agent in different circumstances.

When buying a farm property, you may engage the services of a real estate agent to help you in the process. The buyer’s agent can only prepare offers and negotiate in the best interests of the buyer after a written agreement has been signed between the buyer and the buyer’s agent. This written agreement will contain the provisions of the agreement, including how the agent will be paid and the timeline. The buyer’s real estate agent will represent the buyer’s interest in the transaction. According to the MREC, a seller's agent “works for the real estate company that lists and markets the property for the sellers and exclusively represents the sellers. That means that the seller's agent may assist the buyer in purchasing the property, but his or her duty of loyalty is only to the sellers.” In some cases, the same broker may represent the seller and the buyer, however this must be disclosed in writing and agreed to by all parties.

The seller of the property will typically pay the entire cost of the agent/broker fee. This fee is normally a percentage of the selling price of the property, and typically ranges from 5 to 7%. The fee is split between the buyer’s agent/broker and the seller’s agent/broker (normally equally) based upon the agreed upon terms of the contract. For example, if a property sells for $300,000, and the agreed upon fee is 6% split equally, the seller will pay a 3% fee to the buyer’s broker/agent and a 3% fee to the seller's broker/agent. While this arrangement is typical, the terms can vary widely and are governed by the agreed upon terms stated in the contract. Some buyer agents may require an administrative fee or may stipulate a minimum guaranteed amount for their services.

The fees for real estate agent services are transferred during the settlement process. In situations where the property is offered for sale by owner, without the use of a real estate company, the buyer’s fee will need to be negotiated with the seller. The seller is not under any obligation to pay buyer agent’s fees.

Finding a good farm real estate agent is not as hard as you might think. Maryland FarmLINK has a listing of realtors who have professional training on issues related to buying and selling farmland. Realtors going through this training are given information on zoning and planning issues that impact agriculture, how to check soils on the property, how to check if the property is enrolled in a conservation easement or other conservation program, how to handle agricultural leasing issues, and how the septic law can impact agricultural properties. The listing does not currently cover all Maryland counties, but the training is on-going and more realtors are added in additional counties as the course is completed across the state. Before picking a realtor, take your time to do the research to make sure that they have the skills you need when purchasing new farmland.

Finding General Information about a Property

There are multiple avenues available for researching general information regarding farms. The obvious place to start is the landowner offering the property for sale. Realtors can also help to provide information.

Review Property Assessment Data

- Maryland offers a free Real Property Search database where you can search for property information using either an address, tax ID number or map/parcel number. You can obtain records such as the tax assessed value of the property, prior property sales data, deed reference, map/parcel number, account ID, legal description, use classification, and name and address of the current owner. The Real Property database is often a good place to start to find information on a property.

Review the Deed and Plat

- Maryland offers access to all verified land record instruments through MDLandRec which is a digital image retrieval system for land records in Maryland. This service is currently being provided at no charge to individuals who apply for a username and password. After obtaining a username and password you can search by county for land records based on name or by deed reference number. Note that not all properties have recorded plats. All properties should have a recorded deed however. Interpreting deeds can be a difficult task and it is advisable to seek legal assistance when conducting deed research.

Using GIS Mapping Software

- Online mapping tools can also be useful for garnering more information about the history, location, topography, surrounding farms, building locations, and more. Many county governments use GIS mapping systems as part of their planning and zoning information systems. Check the individual county government website to see if your county offers this service. Other free public mapping software, such as Google Earth, can be used to visualize aerial photographs of the property, and have measuring software for determining approximate acreages of farm fields, proximity to water, and historical imagery. For example, you can use Google Earth to toggle between historical imagery and visualize changes in land use over time.

Identifying Land Use Restrictions

- Most open farmland in Maryland can be used for commodity crops. However, before signing a lease or purchasing a property, it is best to be safe and determine if there are any land use restrictions, particularly if you are considering direct farm sales or value-added sales (e.g. wineries, creameries, etc.), or agritourism (e.g. corn mazes, on-farm weddings, etc.). For an explanation of the many types of zoning restrictions that could impact of the use of farmland, refer to the chapter on Understanding Zoning for New Farm Enterprises. Also refer to Overview of Farmland Preservation in Maryland for more information on how conservation easements may restrict land use options and development potential.

Zoning Ordinances

- Nearly every county in the country has a zoning ordinance and each one is different. However, most counties use similar zoning terminology and most in Maryland are available on-line, along with the zoning maps which define where the ordinances apply. If you are unsure about a particular use, visit the Planning and Zoning office in your county for more information.

Covenants and Easements

- A covenant or easement is a written agreement, usually recorded in land records, that applies conditions to the use of the property. To be fairly certain as to whether or not there are covenants on a property, you will need to consult with your attorney about obtaining a title search. However, you can do some initial research on your own. You may ask the owner or owner’s agent if there are covenants. If you are leasing, not purchasing, your quest for information might stop there. However, you might want to note the response in a lease agreement. Reading through the deed, you might find special covenants or conditions that apply to the land. This is by no means a failsafe method. The covenant may have been recorded after the deed was recorded or the attorney may not have mentioned the covenant specifically in the deed. However, the deed may contain some information that you may want to learn early in the property selection process.

Plat Restrictions

- Many properties will have a corresponding plat recorded in the land records. Plats may contain notes or conditions that are binding upon future owners of the property. Plat notes may indicate where access to the property is restricted, whether or not the property may be further divided, where a storm water easement crosses a farm, and so on. Plat conditions may describe permit requirements, land clearing limitations, forest buffers from streams, etc.

Evaluating Farm Soils

- Experienced farmers often provide one piece of advice to those looking for farmland: “Shop with a Shovel”. In other words, be sure to fully investigate the inherent characteristics of the soil before you buy. Soil characteristics, such as texture, drainage, depth to water table, or depth to restrictive layer can vary greatly across a region, county or even the same field. In general, prime farmland contains deep, well drained soils without restrictive features such as steep slopes.

- How do you find out about the soils on a particular farm? USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) provides on-line soils mapping data that describes the type and features of soils by exact location in Maryland. NRCS developed a website, titled the Web Soil Survey, where you can determine soil classification, ratings, and suitability for your type of farming operation as long as you know the approximate boundaries of the farm. You may want to start with the tutorial or you can go straight to the USDA Web Soil Survey if you are familiar with basic web mapping tools and understand soils nomenclature. Unless the farm is irrigated, you will want to view the “non-irrigated capability class” under Land Classifications. Further, talk to farmers that are familiar with the farm and ask the opinion of your local Soil Conservation District and/or University of Maryland Extension staff.

- Soil structure, or how well the soil particles are held together, is another component of soil quality that needs to be evaluated. A friable, porous soil with good organic matter and microbial activity will support plant life much better than a compacted soil with poor structure. Soil structure can be improved over time with good management and the addition of organic matter.

Testing Your Soil

- Soil testing provides a snapshot of the fertility level of the soil, including levels such as pH, Phosphorous, Potassium, Calcium, Magnesium, and micro-nutrients. When selecting a farm, soil fertility is not as important as the inherent soil properties such as drainage or soil type because poor soil fertility can be improved over time (2-3 years) with the addition of organic matter, manures, fertilizer, lime and amendments. Soils with lower fertility values will require a larger upfront investment in lime and other nutrients, however these costs are minor in comparison to correcting drainage or erosion issues. Soil fertility levels are a more important consideration if leasing farmland for a shorter period of time, due to the shorter payback window. For more details on soil testing, refer to the chapter How to Take a Soil Sample for testing steps.

- In Maryland, regulations limit the amount of manure, fertilizer, or other amendments containing phosphorus that can be applied to soils with excessive phosphorus fertility levels. This restriction should be a consideration for organic farmers who may not be able to use nonP bearing materials for nitrogen sources and/or livestock farmers who need land for manure application. If you intend to conduct soil testing, after you have signed a contract to purchase but before the final sale, remember to include a contingency in the purchase contract to allow

you the time to conduct the testing and the right to terminate the purchase if you are unhappy with the soil test results.

Water Quality and Availability

- Most intensive crops require some type of irrigation. Livestock require daily access to a clean water supply. Farm water sources can include public or municipal water, deep artesian wells, ponds, freshwater rivers and/or shallow wells. Check artesian wells for the gallon per minute water flow and size of the pump installed. Typically, the county health department can provide information on well depth and flow rate based upon the well ID number. Ponds vary greatly in their recharge capacity and size, so ask when the pond was last used for irrigation, how deep it is and if the pond ever goes dry. Drip irrigation will require relatively clean water to prevent clogging of the sand filters and drip tape. It is also advisable to ask if the farm currently has a water appropriation permit (required if using on average over 10,000 gallons per day) if used for agricultural irrigation. If you are buying a farm with the intent of conducting value added processing, you will need to consider the potability of the water source. Water used in food processing activities must be able to meet strict potability standards. Public or municipal water and deep artesian well water typically will meet potability standards. Shallow dug wells, ponds and springs will typically not meet potability standards. In addition food safety regulations, Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) and the Food Safety Modernization Act, require water to be tested routinely to ensure it is safe for use in produce production. As mentioned above, if you intend to conduct water testing, after you sign a purchase contract but prior to the final sale, consider including a contingency in the purchase contract to allow for the time and ability to terminate the contract based on the results of the water testing.

Other Considerations

Neighbors

- After you make the real estate purchase, what kind of neighbors will you have? Knowing your neighbors will give you an idea early on of the types of issues you may experience using the property. In Maryland there are state and county Right-to-Farm laws which provide farmers with a defense that can be asserted, in certain circumstances, when neighboring property owners make nuisance claims. The best preventative measure for neighbor relation issues is communication. Although it is not a guarantee, establishing good communication with neighbors can help minimize legal issues, based on a misunderstanding, from interfering with your farm operation.

Timber Value

- When buying a property, it is always a good idea to estimate the market value of existing timber. Timber can have significant value, which will affect the overall value of the property. Consult with a public or private forester to estimate the value of the existing timber as well as when timber will be ready to harvest. Asking the current landowner when the timber was last cut and whether there is a timber management plan is also helpful.

The Value of a Title Search

- As mentioned previously, a title search is an essential step before purchasing a property. This is not a step you will be able to skip or adequately complete on your own. A qualified attorney or title company, by performing a title search, can determine what easements or other restrictions exist on the property. It is common for farmland to be burdened with easements, such as utility rights-of-way or access easements for neighboring property owners. A title search will allow the purchaser to have a full picture of the extent of these types of property interests. A conversation with the seller or the seller’s agent will often not include mention of the details that will emerge through a title search, and these interests may not be unearthed during a zoning review. Your real estate agent or your lender will typically be able to recommend a local title company who can perform the search and offer title insurance.

Land Preservation Programs

- Land Preservation programs provide a financial incentive (normally a cash payment, though tax credits are also used) in return for the property owner giving up future development rights. The use of land preservation programs is one method to lower the effective price of a farm. While land preservation programs impose some limitations on the use of property (see covenants and easements above), they provide an economic incentive to maintain property as farmland in Maryland. Being in a community of preserved farms provides stability and permanence. Farmers are more likely to invest in their farm enterprises if they know that neighboring farms will not be developed in the near future.

- Maryland offers some of the most progressive land preservation programs in the country. There are several types of land preservation programs that operate in Maryland including the Maryland Agriculture Land Preservation program (MALPF); Maryland Rural Legacy program; and Maryland Environmental Trust program.

Conclusion

Selecting the right farm property is one of the most important tasks to ensure success as a beginning farmer. Taking time to research a farm’s potential productivity, land-use restrictions and capability before committing to a long-term lease or purchase will pay off in the long run.

Understanding Zoning for New Farm Enterprises

Section Author:

- Sarah Everhart, Managing Director, Agriculture Law Education Initiative, Maryland Carey Law

Disclaimer: The following is intended for educational purposes only and is not legal advice.

Choosing the right piece of land can be one of the most important parts of a new farm

enterprise. Unfortunately, fully appreciating the zoning of a piece of property is not as easy as looking at a map. A single piece of property in Maryland can have multiple zoning and planning designations which all need to be understood to completely answer the question of whether it is the right property for a farm enterprise.

Local Zoning

Starting at the local level, a person interested in the zoning of a piece of property can visit the county, or the town if the property is within municipal limits, zoning office. Some jurisdictions have the zoning map online but, to be sure the zoning map is the most current version, it is

advisable to confirm with a phone call or a trip to the local office. Every property has a zoning designation such as “Rural Residential” or “Rural Conservation.” In some cases, a piece of property may have more than one zoning designation, this is referred to as split zoned.

In the zoning ordinance, or applicable section of the local jurisdiction’s code, the zones will be described and the uses that are permitted, prohibited, conditionally permitted or permitted by special exception will be listed. Conditionally permitted uses are typically uses that are

allowable subject to conditions found within the zoning code. A use that is permitted by special exception, will require a hearing and approval from the local board of zoning appeals. A hearing in front of a zoning board of appeals is a quasi-judicial proceeding which can be a challenge to navigate without legal representation.

For all uses, it is important to understand the full extent of what is permitted in the zone and to consider whether zoning restrictions will allow for the farm enterprise to operate fully. For example, if a farmer is contemplating incorporating a retail greenhouse component into an

operation, it is necessary to ensure that both the use (retail) and the erection of the greenhouse building and any required parking area is permitted in the zone. If it is difficult to decipher whether a use is permitted from a review of the zoning ordinance, you can either consult the zoning staff or retain legal counsel to advise you.

If a property is not zoned to permit a use it can be very difficult to change the zoning designation. In Maryland, local jurisdictions undertake the comprehensive rezoning every 10 years. Outside of a comprehensive rezoning, in order for a property owner to be granted a change in zoning he or she must prove the zoning should change due to a substantial change in the character of the neighborhood or because of a mistake in the original zoning.

Types of Zoning

If the property in question is within 1,000 feet of the waters of the State’s tidal waters or wetlands, in addition to the base zone, it will also have an overlay Critical Area zoning designation. Most farmland in the Critical Area is designated as a Resource Conservation Area (RCA), but if your property is adjacent to residential development it could be designated as a Limited Development Area (LDA). Critical Area designations add another layer of zoning restrictions on land such as buffers from sensitive areas.

Another layer of zoning designation in Maryland is the growth tier designation. Pursuant to the Sustainable Growth & Agricultural Preservation Act of 2012, all properties in MD should have a growth tier designation. The tiers are based on whether or not a property is served by a wastewater treatment plant, planned to be served by a wastewater treatment plant, could be developed with properties served by septic systems, or whether the land is planned for agriculture or conservation. Tier designations may not impact all farm enterprises, however, a

tier designation is important if you plan to develop (build residences, subdivide, etc.) a property. Tier maps can be found at the local jurisdiction’s zoning office or on the MD Department of Planning’s website.

Planning Documents

Local jurisdictions also create long-term planning documents called comprehensive plans. Although comprehensive plans are technically planning rather than zoning tools, the plans can have a great impact on the use of property, both now and in the future. In these plans, a local

jurisdiction classifies the current and future plans for all the property within and surrounding the political boundaries of the jurisdiction. Comprehensive plans are updated every 10 years and it is important to examine these documents to understand the jurisdiction’s future plans

for the property in question and the surrounding properties. For example, a comprehensive plan may indicate a property is bordered by land designated for future heavy industrial uses. Further, local jurisdictions are required to make zoning decisions which are consistent with the

comprehensive plan. No one can predict future development with certainty, but looking at a jurisdiction’s comprehensive plan can provide you with valuable information about the planned future uses of properties.

Conclusion

A person interested in a piece of property for a new farm enterprise should not assume, based on the current use, that the property is not necessarily zoned for either that use or related uses. When a local jurisdiction undergoes a comprehensive rezoning, in some instances,

certain uses may be allowed to continue despite the updated zoning no longer allowing the use. These uses are referred to as non-conforming uses. Non-conforming uses are typically allowed to continue, but, are subject to limitations such as a prohibition on expansion and may be disallowed all together if the use is abandoned for a certain period to time. Although, a person who is interested in a piece of property for a farm enterprise can, by taking the steps outlined above, find out a good deal of information about the property, it is always a good idea to consult with an attorney experienced in land use and real estate matters before signing any contract or lease for a new farm enterprise.

Understanding Soil and Soil Health

Section Author:

- Neith Little, Extension Educator, University of Maryland - Urban Agriculture

How well you understand soil, and how well you manage the soil’s health, will have a large impact on the productivity of the farm. This section will introduce key concepts that will help understand soils and good farming practices that will help manage overall soil health.

What is soil?

Soil is the result of a mind-bogglingly long process wherein the rocks of the earth’s crust are gradually broken down into very small particles by the environment and living organisms. Soil is made of tiny particles of rock (sand, silt, and clay are size classes of tiny rock particles), dead biological material (organic matter), and living organisms (from “macroinvertebrates” like worms down to microbes, fungi, and viruses).

How can I learn about my soil?

Soils have physical and chemical properties that affect how well the soil can grow plants. Important soil properties include layers, depth, texture, structure, compaction, density, fertility, pH, cation exchange capacity (CEC), organic matter, drainage, and water holding capacity. Additional references to help you learn about some of these properties are listed below in the Additional Reading section.

You can get a rough assessment of some soil properties by looking at the soil itself. A soil laboratory can conduct more precise tests of your soil’s properties which will give you more accurate, actionable results. The following paragraphs will describe some of these resources in more detail.

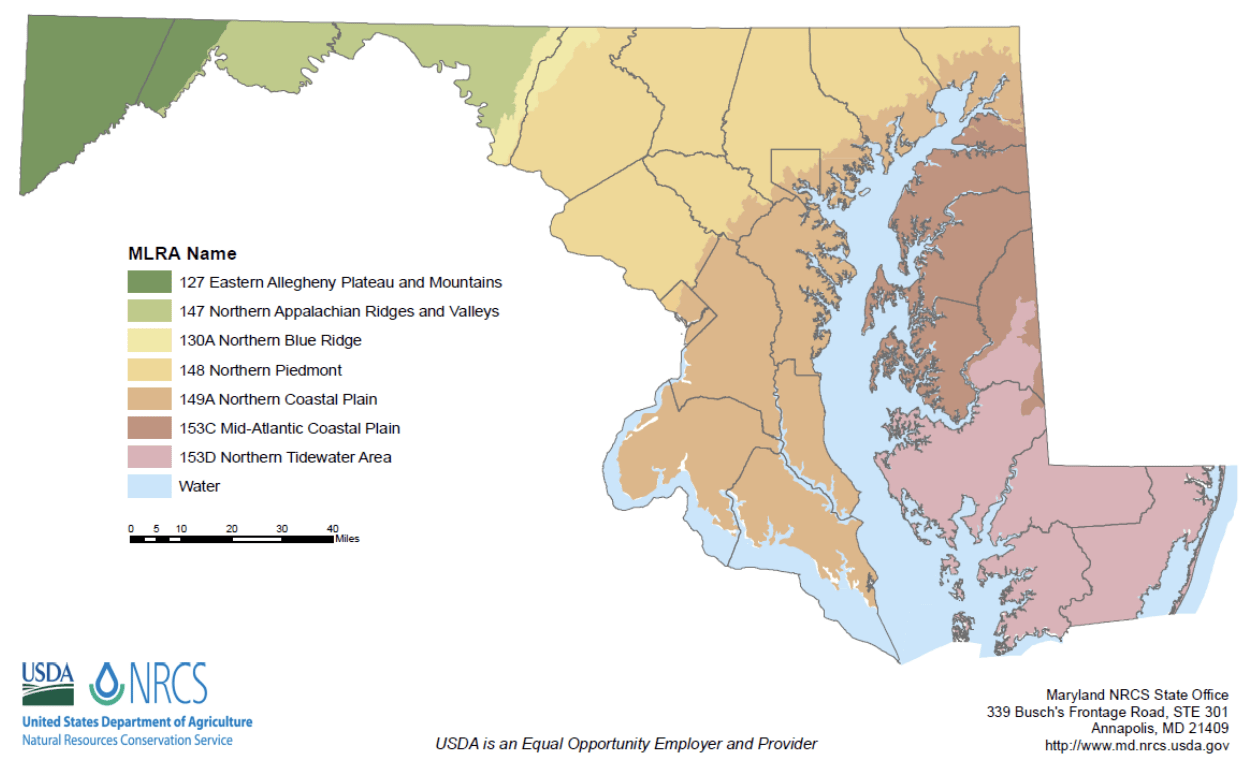

In Maryland, the geographic location of your farm will dramatically affect what kind of soil you have to work with. Broadly, Maryland can be broken up into three soil categories: Appalachian Mountains, Piedmont plateau, and Coastal Plain (Fig. 1). A lot of soil diversity exists within these regions, but in general mountain soils tend to be more rocky and steep, the Piedmont plateau tends to be gently hilly with many small streams and a loamy soil texture, and the coastal plain tends to be marshy with patches of mostly sand texture and patches of mostly clay texture.

To find detailed information about the soil on your specific farm, the best place to start is the Web Soil Survey, which is a searchable digital soil map operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Read in particular what the soil map says about your soil’s texture, drainage class, and slope.

Major Land Resource Areas for Maryland and the District of Columbia

Figure 1: Maryland’s soil regions, as mapped by the USDA-NRDCs. Broadly, Maryland can be broken up into three soil categories: mountains (127,147,130A), Piedmont plateau (138), and coastal plain (149A,153C,153D).

Texture is arguably the most important property of a soil. A soil’s texture is its ratio of sand, silt, and clay (the different size classes of soil particles). At the scale of a farm field soil texture is impossible to change, and soil texture affects many of the other properties, such as drainage, water holding capacity, and fertility. For more information about soil texture, see the Additional Reading below.

Note that in small fields and in urban areas the soil maps on the Web Soil Survey may not be as accurate. It is important to check how the Web Soil Survey predicts the soil within an area. Both quick field methods and accurate lab methods have a role to play in this process. Field based soil quality measurement methods are fast, inexpensive tools to get a qualitative “feel” for your farm and laboratory soil testing methods are the gold-standard for quantitatively measuring your soil’s properties so that you can make informed management decisions. The USDA-NRCS offers detailed information about both field-based and laboratory soil analysis methods.

Soil Testing

Different testing methods are used to measure different qualities of the soil. There is no one soil test that will tell you everything. Before doing a soil test, you need to know what soil property to measure. The most common test is a soil fertility test, which typically measures a soil’s pH, organic matter, and nutrient availability. All three of these soil properties are extremely important to the soil’s fertility -- its ability to grow high yielding, high quality crops.

The pH scale is a measure of the balance of hydrogen ions (H+) and hydroxide ions (HO-) in the soil. At the low end of the pH scale, there are many hydrogen ions and the soil is considered acidic. At the high end of the pH scale there are many hydroxide ions and the soil is considered basic. A moderate pH, between 6 and 7, is ideal for most crops. In this pH range, plant nutrients are most available to the plants’ roots, and elements that are toxic to plants, like aluminum, are bound tightly to the soil particles. For more about pH, and how to get it in that ideal range, see the Additional Reading section below.

Organic matter is dead biological material in varying states of decay. Organic matter is an important source of slow-release nutrients for plants and other organisms in the soil. Organic matter also increases the soil’s water holding capacity and can improve soil structure. An organic matter measurement of 3 to 4% is considered good. For more on how organic matter affects soil quality, see the Additional Reading section below.

Plants need nutrients, like nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) to build their bodies. A soil fertility test will report the amount of “plant available nutrients.” This is different from the total amount of nutrients in the soil, because a large proportion of the nutrients are bound into minerals and organic matter where the plant roots cannot access them. These bound up nutrients may become available in future years, but they will not be available in the current growing season. Soil fertility test methods have been developed to estimate the amount of nutrients that are available to plants, and to predict whether adding additional nutrients will increase crop yields.

Different soil fertility tests have been developed to be specific to the soils and climate of different geographic regions. This is why it is important to use a soil testing lab recommended for your state. For example, the plant nutrient nitrogen is very mobile in water, and here in Maryland we get a lot of rain. Because of this, in Maryland by the time you collect a soil sample, mail it off to the lab, and get your soil fertility test results back, the amount of available nitrogen in the soil has probably already changed. For this reason, in Maryland most soil tests will not report nitrogen availability and will instead recommend adding nitrogen to your soil based on book values for how much nitrogen different crops will need. It is also recommended to add nitrogen in small amounts throughout the season, so that it is less likely to be lost before your plants can take it up. Building up soil organic matter and incorporating nitrogen-fixing leguminous cover crops into your crop rotation are also good ways to provide some slow-release nitrogen to your crops.

Before you decide whether to add nutrients to your soil using fertilizers or composts, it is important to know that in Maryland farmers who sell at least $2,500 worth of crops per year, or who raise a certain amount of livestock, are legally required to have and follow an approved nutrient management plan. The University of Maryland Agricultural Nutrient Management Program can help you comply with this requirement, and plan how to provide your crops the amount of nutrients that they need to grow well.

Farming practices that improve soil health

Above you read about how to test soil fertility and how to improve its pH, organic matter, and nutrient availability. Additional farming practices that can improve soil health include minimizing tillage and incorporating cover crops into your crop rotation. Reducing tillage helps build soil structure and reduce compaction. This is important, because plant roots need both air and water, and when soil has poor structure or is compacted, there is little space in the soil for air and water, and plant roots have difficulty growing. Cover crops increase soil organic matter, help build good soil structure, and feed the many organisms that live in the soil. A healthy soil ecology is important for nutrient supply and for suppression of pests and diseases.

To learn more about soil health, and practices you can adopt to improve your soil, see the Additional Reading section below.

Additional reading on soil management and soil health

- Soils. Cornell Cooperative Extension Agronomy Fact Sheets

- Guide to soil texture by feel. USDA-NRCS

- Soil organic matter is an essential component of soils. UMD Extension factsheet 1045, by Jarrod Miller

- Soil pH affects nutrient availability. UMD Extension Factsheet 1054, by Jarrod Miller

- Soil pH management and determining liming rates. UMD Extension Soil Fertility Management Bulletin 5.

- Lowering soil pH for horticulture crops. Purdue Extension HO-241-W, by Michael V. Mickelbart and Kelly M. Stanton.

- University of Maryland Extension Agricultural Nutrient Management Program (UME-ANMP)

- UME-ANMP Soil Testing recommendations

- Precision soil sampling helps target nutrient application. UMD Extension Factsheet 1046, by Jarrod Miller and Craig Yohn

- Manure as a natural resource: Alternative management opportunities. UMD Extension Bulletin 420, by Jarrod Miller

- Comprehensive assessment of soil health. Cornell University, by Bianca Moebius-Clune, D. Moebius-Clune, and colleagues

- Soil Health website of the United States Department of Agriculture--Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS)

- Building Soils for Better Crops by Fred Magdoff and Harold van Es, published by Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE)

- Managing Cover Crops Profitably by Greg Bowman, Craig Cramer, and Christopher Shirley, published by SARE

Overview of Farmland Preservation in Maryland

Section Author:

- Margaret Todd, Law Fellow, Agriculture Law Education Initiative

Disclaimer: The following is intended for educational purposes only and is not legal advice.

Federal and state programs aimed at the protection and conservation of rural lands have been around for decades. Agricultural preservation programs are popular in Maryland and can be useful tools for new and beginning farmers to consider before and after purchasing property. There are many incentives for farmers to preserve farmland, including but not limited to, tax incentives, securing operational funding, personal conservation goals, and preserving a family legacy. Farmers, however, prior to enrolling in a preservation program, need to have to a full understanding of how farmland preservation will impact future land uses.

Generally, there are three main types of farmland preservation programs in Maryland:

easement sale, easement donation, and transferable development rights sale. The general purpose of preservation programs is to set aside large blocks of rural lands for the protection of open-space, natural and scenic resources, and to foster rural industries such as agriculture and forestry by limiting non-agricultural uses on existing rural and agricultural lands.

What is a Conservation Easement?

In this context, an easement refers to restrictions placed upon the land that essentially removes certain rights to develop on the property. An agreement called a “deed of conservation easement” is made, wherein a landowner agrees to conserve several acres of land and in exchange receives cash payments or tax credits. The easement is conveyed to an eligible easement holder, typically the local or state government or a land trust. Deeds of conservation easement are usually recorded in the county land records office. A landowner may sell or otherwise convey land protected with a conservation easement. Since the easement is permanent, however, the restrictions “run with the land,” meaning they apply to the land perpetually regardless of the owner or operator, and therefore apply to all future owners and lessees of the property.

The easement often limits the development of property through conditions on allowable land uses, such as limiting or prohibiting subdivision and commercial land uses. Enhanced conservation practices may also be required, for example creating riparian buffers and creating wetland protections plans. A conservation easement typically does not grant public access to a property, but the easement holder does gain a right to access the property to monitor, as well as the authority to enforce, the terms of the easement. The landowner and the easement holder work together to finalize the terms of the easement, which are tailored to fit a landowner's individual situation.

Specific terms may be mandated, depending upon the program or easement holder. Most conservation easements provide a degree of flexibility to adapt to future needs by providing the holder discretion to approve changes under discretionary approval clauses or to issue compatible use authorizations. However, the basic principles of contract interpretation apply to conservation easements and the terms that restrict the use of the land, including restrictions on development, uses, and open space maintenance, can be strictly construed if a conflict arises. For example, if “commercial activities” are prohibited under the easement, a farmer who wants to expand or add a retail component to the farm may need to seek approval from the easement holder first. Careful attention to the terms of a deed of conservation easement, therefore, is necessary to ensure it adequately incorporates considerations for the economic concerns and viability of the farm as a continuing business entity.

Easement Sales

Maryland Agricultural Land Preservation Foundation

- The Maryland General Assembly created the Maryland Agricultural Land Preservation Foundation (MALPF) in 1978 with the purpose of acquiring easements to restrict the use of agricultural lands in order to “curb the spread of urban blight and deterioration,” and “protect agricultural land and woodland as open-space land.” MALPF was one of the first state easement purchase land preservation programs in the country and it continues to be one of the most successful. The program is administered by county and State in an equitable partnership.

- In general, owners of farmland that meets the minimum size and soil eligibility criteria and is located outside a 10-year water and sewer service area can apply for an easement sale. Counties rank the applications to be considered in a given easement acquisition cycle based on factors like productivity, location, conservation and management plans, and commitment; each county can have its own unique local criteria as well. Two independent fee appraisers are selected to establish a fair market value for each property. The Foundation calculates an agricultural value for the property, which is its agricultural production value. Each county prioritizes its applicants by its own ranking system and forwards its prioritized list to the state which makes the offers to selected applicants. Upon selection and settlement of the sale, the landowner is typically paid through an Installment Payment Plan (IPP) over the course of 10 – 30 years. The Foundation web page provides numerous fact sheets to help applicants navigate the easement acquisition process and answer questions about permitted uses for preservation properties.

Rural Legacy Program

- Established in 1997, Maryland’s Rural Legacy Program is a state funding program administered through the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) that encourages local government and private land trust sponsors to partner together in acquiring conservation easements from willing landowners to “preserve large, contiguous tracts of open space that contain valuable agricultural, cultural, forestry or natural resources.” The Rural Legacy program focuses on land conservation investments that protect the most ecologically valuable properties that directly impact the Chesapeake Bay and local waterway health. Rural Legacy easements typically require the preparation and approval of a Soil Conservation and Water Quality Plan and/or a Forest Stewardship Plan. The program requires applicants to apply for a Rural Legacy Area designation. If an area is approved by the Rural Legacy Board, then property owners within a Rural Legacy Area can apply to sell an easement. The program also allows for property owners to donate a conservation easement or to sell or donate a fee simple interest in the qualifying real property. The application process and Rural Legacy Program Grants Manual are provided on the DNR website.

County Easement Programs

- Certain counties, such as, Harford, Frederick, Carroll, Howard, Calvert, and Anne Arundel, have county easement purchase programs. Such programs vary widely in structure, but the application requirements and easement restrictions are usually patterned after the state easement program. Contact information for each county’s relevant department are provided in the Table 1.

MARBIDCO Next Generation Farmland Acquisition Program

- The Maryland Agricultural and Resource-Based Industry Development Corporation (MARBIDCO) is a quasi-public corporation with the mission to “to help Maryland’s farm, forest, and seafood businesses achieve sustainable viability and profitability now and into the future.” Through its Next Generation Farmland Acquisition Program MARBIDCO offers up to 51% of the Fair Market Value (FMV) of the land only (with a cap of $500,000), on a competitive application basis, to qualified young or beginning farmers who have trouble entering the agricultural profession due to high land costs or inadequate financial capital. Following the land sale transaction, the purchaser is required to sell a permanent easement on a land to a rural land preservation program (thus extinguishing the development rights on the property forever). Once a permanent easement has been subsequently facilitated, the purchaser is obligated to repay MARBIDCO the original Next Gen Program Option Purchase amount, plus a 3% administrative fee. Interested applicants, after identifying a property, should start the process by contacting the county office (Table 1) and determining whether a particular property is not already under a conservation easement and whether it is a potential property for the program.

Easement Donation

- Easement donations operate to a large extent in the same manner as easements sales, the largest difference being that the landowner does not receive payment for the lost development value of the property. Instead, the landowner is allowed to claim a charitable deduction for federal income taxes and a credit for state income taxes for the lost value associated with protecting the land. In addition, there is a property tax credit and possible federal estate tax exemptions.

- To qualify for the federal deduction under Internal Revenue Code 170(h), a donation has to meet three general requirements. The donation must: (1) be of a qualified property interest (value determined by a qualified appraiser), (2) be made to a qualified easement-holder, and (3) be made exclusively for conservation purposes protected in perpetuity. There are guidelines for what makes appraisers and easements holders “qualified.” County easement programs may not always require a “qualified” appraiser, but landowners intending to claim state and federal tax deductions should comply with the law and regulations governing deductions for contributions of conservation easements. Depending upon the land use type and the landowner's taxable income, this deduction can be claimed across multiple tax years, which is often needed as many landowners lack the income to claim such a large donation in a single year. Maryland income tax credit is in addition to other tax deductions. The deduction is limited to $5,000 per year and the landowner can carry forward the remaining credit amount up to 15 years for a maximum credit of $80,000. The DNR has a useful summary page for federal and state tax benefits of conservation easement donations.

- For estate-tax purposes, a conservation easement limits the amount of development that can occur, thus lowering the appraised value of the land and reducing the taxable estate. This makes conservation easements effective tools for reducing estate taxes. The Agriculture Law Education Initiative has a guide, Conservation Easements: A Useful Tool for Farm Transition and Estate Planning that provides more details on several ways agricultural land preservation can also serve as an estate planning tool.

Maryland Environmental Trust

- The Maryland Environmental Trust (MET) was created in 1967 to “to conserve, improve, stimulate, and perpetuate the aesthetic, natural, health and welfare, scenic, and cultural qualities of the environment, including, but not limited to land, water, air, wildlife, scenic qualities, [and] open spaces.” MET determines whether preservation of the offered land would confer a significant public benefit in the form of woodland, wetlands, farmland, scenic areas, historic areas, wild and scenic rivers, and undisturbed natural areas. The easement donation process through MET is outlined on their webpage.

Local and Private Land Trusts

- Local or private land trusts may also take on conservation easements. Often, MET will partner with other organizations whose purpose and goals are similar through cooperative agreements or as an easement co-holder. Collaborative agreements between land trusts helps avoid unnecessary competition and allows the trusts to increase land conservation efforts with expanded funding options and shared expertise. The MET provides a list of local land trusts that operate in Maryland. Scenic Rivers Land Trust, Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage and the Eastern Shore Land Conservancy are examples of private land trusts that can be the recipient of a donated conservation easement. Contacting the county planning or land preservation office is the best way to gather information about local land trust options (see Table 1).

- For tax purposes, any private land trust chosen for an easement donation must be “qualified” according to federal and state guidelines. For federal tax deductions, the organization must be either run by the local or state government or a non-profit organization (according to IRC § 501(c)(3)), with the purpose of protecting and enforcing the conservation easement. The land trust generally must have an established monitoring program such as annual property inspections to ensure compliance with the conservation easement terms and to protect the easement in perpetuity. The organization must also have the resources to enforce the restrictions of the conservation easement, which may be in the form of conservationists who inspect the property and prepare monitoring reports. The Maryland state tax credit is only available to perpetual easements conveyed to MET, Maryland DNR or MALPF, and approved by the Board of Public Works.

Green Print Program

- In the late 1990’s MDNR began identifying the most ecologically important lands in the State, referred to as Maryland’s Green Infrastructure (GI). Through the Green Print Program the State makes efforts to delineate and protect the most ecologically significant lands in the state using up-to-date mapping techniques and making offers to landowners for targeted acquisitions and easements. There is no application process because the state will identify and make offers for lands it deems eligible. Maryland’s Green Print Map is one resource that displays information about whether or not a property may have a MALPF, MET, or Rural Legacy easement.

Purchase of Development Rights (PDR) & Transferable Development Rights (TDR)

- Purchase or Transfer of Development Rights programs are another vehicle for preserving rural land and encouraging development in existing communities. Approximately ten Maryland Counties have programs that allow development rights to be sold or otherwise conveyed to increase the development potential on another property. A key approach to transferable development rights programs is to use private sector investments, rather than public sector funds, to preserve farmland.

- Through voluntary TDR programs, developers buy development rights from owners of rural land within a county’s designated “sending areas,” which county governments identify for preservation. A perpetual conservation easement is then placed on the property from which development rights were purchased or transferred. Developers can use their purchased development rights to build more residences, increase commercial square footage or gain other marketable features in “receiving areas,” located in areas where development and infrastructure are planned and desired. For an explanation of the many types of zoning restrictions that could impact of the use of farmland, refer to the chapter on Understanding Zoning for New Farm Enterprises. Also, contact your local county planning department to determine whether they have PDR or TDR programs and how to participate.

Conclusion

Agricultural conservation easements have become one of the primary tools for farming communities and farmland preservation advocates to preserve hundreds of thousands of acres of working agricultural lands with numerous entities engaging in this work at the local and state level.

Many resources are available to farmers interested in land preservation. An attorney should be consulted about the need for a title search to help determine if an easement or covenant has been sold or donated for a property before initiating a property purchase. Additionally, consulting an attorney can help farmers fully understand the implications of permanently encumbering the land and can help with negotiating the terms of an easement to ensure the landowner’s interests are also protected

Table 1: Maryland County Land Preservation Program Participation Table

| County Contact Information | MALPF | MET | Rural Legacy | Green Print | County Programs | TDR/PDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alleghany County 301-777-5955 ext. 210 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Anne Arundel County 410-222-7317, ext. 3553 /3046 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Baltimore County 410-887-3480 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Calvert County 410-535-1600 ext. 2336 | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Caroline County 410-479-8100 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Carroll County 410-386-2214 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Cecil County 410-996-5220 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Charles County 301-645-0692 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Dorchester County 410-228-3234 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Frederick County 301-600-1474 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Garrett County 301-334-1923 | X | X | X | |||

| Harford County 410-638-3235 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Howard County 410-313-5407 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Kent County 410-778-7475 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Montgomery County 301-590-2823 | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Prince George's County 301-574-5162 ext. 3 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Queen Anne's County 410-758-1255 | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Saint Mary's County 240-309-4021 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Somerset County 410-651-1424 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Talbot County 410-770-8030 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Washington County 240-313-2430 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Wicomico County 410-548-4860 | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Worcester County 410-632-1200 ext. 1302 | X | X | X | X |

Resources and Web Links - Farm Establishment

- Agricultural Conservation Leasing Guide

- Agricultural Water Law in Maryland: The Water Appropriation Application Process and Use in a Time of Drought

- Conservation Easement Audit Techniques Guide published by the IRS

- MARBIDCO Next Gen Program page

- MD FARMlink

- Maryland Land Preservation Fact Sheet

- Maryland Land Trust Directory, Maryland Environmental Trust

- Maryland’s Rural Legacy Program, Maryland Dep’t of Nat. Res.

- Maryland Transfer of Development Rights Best Practices, Maryland Dept. of Planning

- Soil Web, UC Davis

- Tax Benefits of Conservation Easement Donations, DNR

Farm Establishment Review - Questions to Ask Yourself

- Have you identified a piece of property to farm that will meet your needs (production, acreage, affordability and location)?

- Have you contacted local agriculture agencies for more information and any questions (Cooperative Extension, Soil Conservation, USDA Farm Service Agency)?

- What are the zoning and restrictions on your property?

- Have you researched the property deed, covenants and easements?

- Have you explored your soil type through web soil survey, in person and gotten a soil test?