Fig. 1 BMSB adult

The Brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) Halyomorpha halys (Figs. 1 and 1a) was accidentally introduced into the United States in shipping containers arriving from Asia. The first confirmed specimen was collected in Allentown, PA in October 2001, although there is evidence that it was collected from black light traps in New Jersey as early as 2000. Since becoming established in Pennsylvania, the BMSB has spread throughout the mid-Atlantic as far south as Virginia. It also has been found in several southern and Midwestern states (as well as some west coast states). The BMSB more than likely has a single generation per year in Maryland (although it could have two). Adults emerge from over-wintering sites during late May through the beginning of June. They mate and lay eggs from June through August and probably into September. The eggs hatch into small black and red nymphs that go through five molts throughout July and August. Next generation adults begin to appear in mid-August. Their flights for overwintering sites start in mid-September and continue through October and November.

When BMSBs feed on apple, peach, nectarine, pepper, tomato, and green beans they can cause discolorations, sunken lesions and internal white and brown spotting rendering the fruit unmarketable (Figs. 2 and 3). The damage from BMSB feeding is especially injurious on some fruit and vegetables where it can deform the fruit more severely than other stink bug species (Fig 2). What could be causing such severe damage from this stink bug’s feeding? The brown Euschistus spp and green stink bug, Acrosternum hilare (Say) are known to transmit yeast spot disease in soybeans and we wondered if the BMSB could be transmitting microorganisms into fruit or vegetables through its saliva. We undertook a series of studies to see what microorganisms, if any, are associated with BMSB feeding.

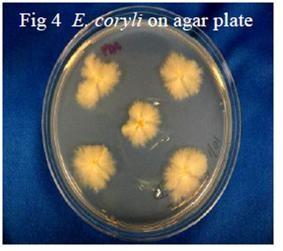

Study: Fruit and vegetables were collected from several farms and a research station in western Maryland where the BMSB was found to be in very high populations. Fruit displayed heavy feeding damage as shown in figures two and three. The fruit surface was disinfested with 95% ethanol, the outer epidermis removed aseptically, and the internal discolored tissue plated on PDA or Malt Extract agar plates. After 4 days, white yeast grew from the tissue pieces (Fig 4). The yeast had both bud cells and asci containing 8 ascospores with long, whip-like appendages. Based on morphology, the yeast was identified as Eremothecium coryli, a plant pathogenic yeast. The isolates were subjected to molecular analysis of the 28S rRna gene sequence (MIDI Labs, Newark, DE) and were a 100% match to Eremothecium coryli U43390 (GenBank).

To verify that the BMSB was responsible for the transmission of the yeast and not other stink bug species, greenhouse cage trials were conducted. Over 50 BMSB adults were collected from the Western Maryland Research andEducation Center near Keedysville, MD in September 2010. The stink bugs were transported back to the University of Maryland, College Park greenhouse facility. Two petri plates were placed in the cage with the stinkbugs. One plate had tap water and the other had a 15% sucrose solution. A series of unblemished fruit (apple (McIntosh), Bartlett pear, and nectarines) and vegetables (tomato, green pepper, and green beans) purchased from grocery stores over a four week period were placed in a circle in the center of the cage. Fruit and vegetables were removed when they showed feeding damage, which usually occurred within 5-7 days. Fruit or vegetables were then dissected and plated as described above. E. coryli was recovered from all plated fruit and vegetables (Fig. 5).

A third study was conducted where unblemished store-bought apples and tomatoes were inoculated with the isolated yeast. Damage symptoms were reproduced, and the yeast was reisolated from the lesions, although most of the lesions were not as severe as when BMSB caused them.

To our knowledge this is the first report of the BMSB transmitting the yeast Eremothecium coryli in the United States.

Discussion: Does this mean that the yeast is entirely responsible for the brown spots found in the fruits and vegetables caused by BMSB feeding? NO it does not. There could be enzymes and other saliva constituents that are responsible for the severe damage in the fruit and the yeast is simply present and takes advantage of the damaged cells. This yeast may play a role in the damage, but not be primarily responsible for it. When we plated areas of the fruit where the damage was more severe, i.e., brown lesions vs. white lesions or sunken spots in the fruit where little internal discoloration was seen (Fig. 6), we obtained 10X the number of yeast cfus from the spot with the greater damage. This does not show conclusively that the yeast is the "cause" of these severe lesions as the yeast could just grow better in an area more damaged from saliva. The stink bug species Nezara viridula (L), Acrosternum hilare and Euschistus servus (Say) have been shown to vector the plant pathogenic yeast E. coryli, which causes yeast spot on soybean and lima bean, fruit rot of tomato, and stigmatomycosis in cotton. Whether the BMSB transmission of the yeast can directly cause these same diseases is currently being studied.

In addition, work is continuing at the University Of Maryland Department Of Entomology examining what role saliva of the BMSB plays in creating fruit damage. Other microorganisms also have been recovered sporadically from BMSB feeding sites (only the yeast has been consistently recovered from feeding sites); what role they play is still to be determined.