FS-2023-0671 | December 2023

Leadership and Conflict on the Farm

If you are reading this in the evening, it's likely that you experienced conflict on your farm today. Conflicts arise when two parties perceive each other to have incompatible goals (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2006). At the same time, the presence of conflict also indicates that both parties are invested in the situation. People with leadership roles on agricultural operations have the opportunity to benefit from good conflict management processes. When people are passionate about what they are doing, differing opinions on how to do something are going to arise, making conflict an inevitable part of any worthwhile endeavor (Bennett, 2023). While you probably can't eliminate all disagreements, developing your conflict management skills can increase efficiency and improve employee retention. This fact sheet will provide you with actionable skills to take back to your team.

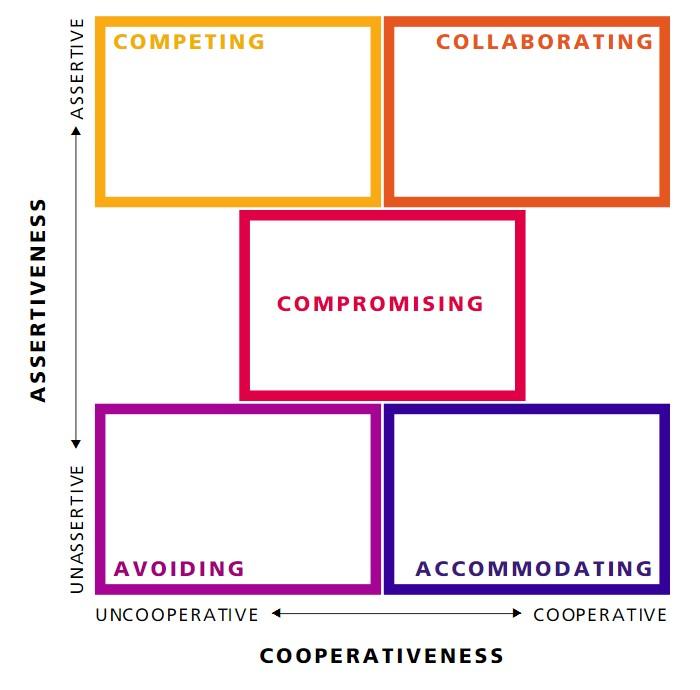

Conflict Styles

If you want to add new strategies to your management tool belt, understanding your own relationship with conflict is a good place to start. Management researchers Thomas and Kilmann (1978) proposed a model of conflict handling behavior with five “conflict-handling modes”: competing, collaborating, compromising, avoiding, and accommodating (Figure 1). They propose that different conflict-handling modes are appropriate for different situations, and that reflecting on which conflict-handling modes you use most frequently can help you choose to consciously manage conflicts more productively in future.

Let’s consider some examples of how different conflict-handling modes might come into play in farm management. When it comes to daily tasks on your farm, it's likely you have an opinion on the best way to complete them. Do you ensure that your team completes farm tasks the way you think they should be done, or do you let farm workers navigate a task their own way? Thomas and Kilmann would call the first strategy a “competing” conflict-handling style and the latter an “accommodating” style. In some cases, the first (“competing”) approach may ensure that a task gets done efficiently and safely, but in other cases the second (“accommodating”) approach might have more positive results. For example, if a farmworker does not follow instructions to wash their hands after using the bathroom, the farm manager might need to retrain the employee or monitor and correct their behavior to prevent a food safety outbreak. On the other hand, if a farmworker has an idea for how to harvest crops in a more ergonomic way, letting them try their idea can show your team that you value their experience and might prevent repetitive motion stress induced injuries. Everyone utilizes all five conflict styles some of the time, but we generally have preferences. As we can see from the examples above, different styles have unique strengths and weaknesses depending on the context in which the conflict arises.

Ultimately, one of our most useful tools for navigating any conversation is the understanding of ourselves. Understanding what makes us upset helps us process our emotions, minimizes our lashing out, and helps us navigate difficult situations with increased collaboration and creativity. Additionally, utilizing the skills presented here can have a snowball effect on your operations and encourage others to communicate effectively as well.

Reflective Listening

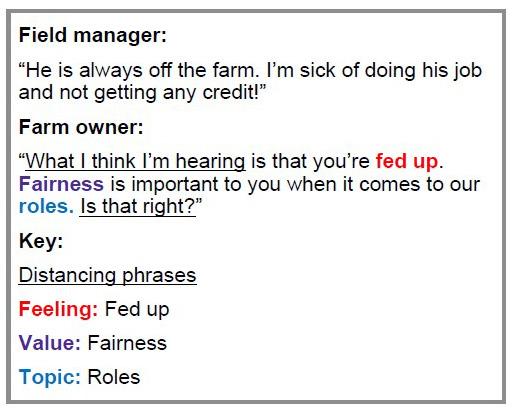

One of the most important conflict management skills is reflective listening. This can help you make the most of a conversation. By responding to someone in a way that names the topics, feelings, and values they present, you can make even the angriest person feel heard and understood. Utilizing reflective listening helps you build rapport with your employees and co-workers.

To use reflective listening, listen to someone’s concerns and then reflect back to them what you have heard. When we reflect back something that we hear, we are not yet communicating our opinions about what a person has said. Using the example at the right (Figure 2), the farm owner lets their field manager know that they recognize that the field manager feels “fed up,” irrespective of whether the farm owner believes that the field manager’s feelings are “valid” in this situation. Other appropriate feelings to reflect in this example would be “frustrated” or “underappreciated.” Take note that the farm owner in this situation opens and closes their statement with Distancing Phrases such as “What I’m hearing is…” and “Is that right?” Distancing Phrases are phrases you can use to show that you hear what someone has to say without agreeing with what they are saying.

In the example above (Figure 2), the farm owner also clearly identifies the feelings, values, and topics that are at the center of the conflict. This strategy can help you problem-solve in more meaningful ways.

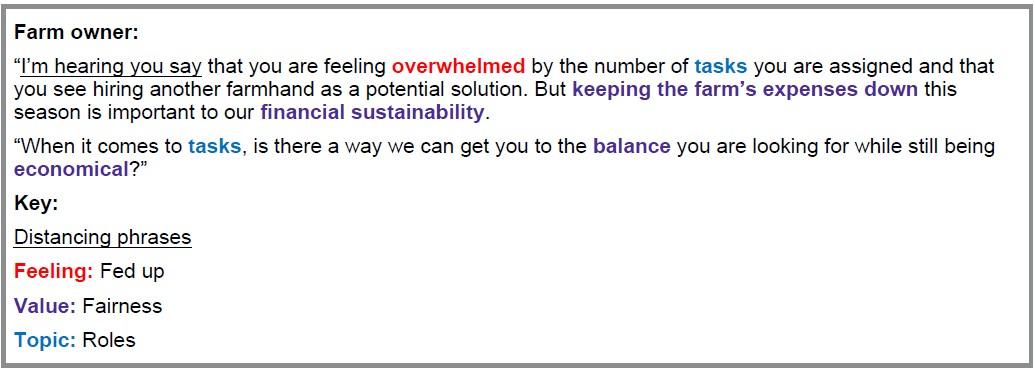

You can also use the strategy of identifying feelings, values, and topics later on in the conflict management process. If stakeholders propose solutions that seem unachievable or that conflict with your needs, try acknowledging that potential solution. Then, juxtapose the opposing values to stimulate thinking that addresses everyone's concerns. request for brainstorming solutions (Figure 3).

These small additions to how you speak with someone about a conflict can foster a sense of collaboration on the farm while minimizing time-draining misunderstandings. Note that in the example in Figure 3, the farm owner ends their statement with a question, asking the field manager to be part of identifying a solution. Questions like this can help lead to formulating solutions that work for all parties.

If someone responds aggressively to your attempts at reflective listening, you may need to use de-escalation strategies to bring the tension down before you are able to have a productive conversation. The Crisis Prevention Institute (2022) lists their top 10 de-escalation tips as

- “Be empathetic and nonjudgmental”

- “Respect personal space”

- “Use nonthreatening nonverbal communication” (body language)

- Keep your own emotions in check and stay calm

- Listen for what emotions or fears are underlying the person’s aggression

- “Ignore challenging questions” and “redirect their attention to the issue at hand”

- Set “respectful, simple and reasonable limits”

- “Choose wisely what you insist on”

- “Allow silence for reflection,” even if it feels awkward

- “Allow time for decisions”

Curiosity, Judgment and Solutions

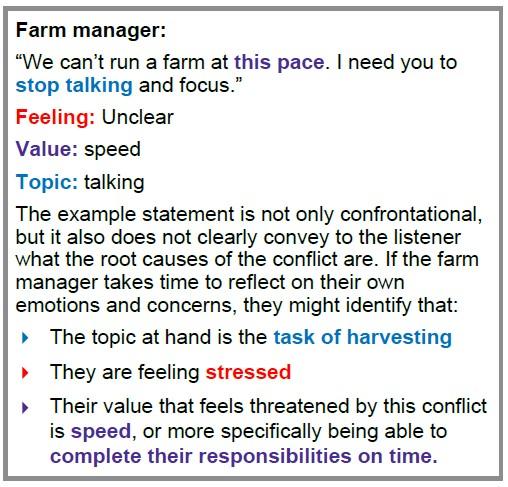

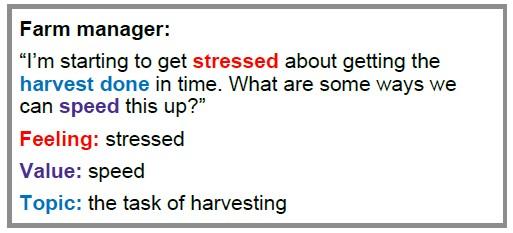

You may find that people with a strong sense of responsibility can have a tendency to communicate through solutions. For example, if a farm owner or manager is beginning to worry that harvesting a row is taking too long, they may say something like the statement in Figure 4.

In the example in Figure 4, the phrases "stop talking" and "focus" may be offered as potential solutions to speeding up the harvest process. Regularly communicating this way may get your needs met quickly, but it can become demoralizing over time. While the concern that talking is slowing the team’s efforts may be valid, this statement puts people on the defensive by attacking their professionalism. Imagine how you would feel if someone spoke this way to you. The farmworkers hearing this statement are likely to feel judged or attacked.

You can model collaboration for your team by taking a moment to reflect on your feelings, and what values and topics are causing those feelings (Figure 5).

You can model collaboration for your team and communicate your concern more clearly by stating how you are feeling about the topic at the center of the conflict, and asking for input on solutions that would align with your values (Figure 6). Approaching the conflict with curiosity instead of judgment can better engage your team in identifying and buying into solutions.

Imagine someone saying each of the statements in Figure 4 and Figure 6 to you. How would you feel in each scenario? Which statement would be most likely to get you to help solve the problem? Which statement would make you want to keep working for the farm manager?

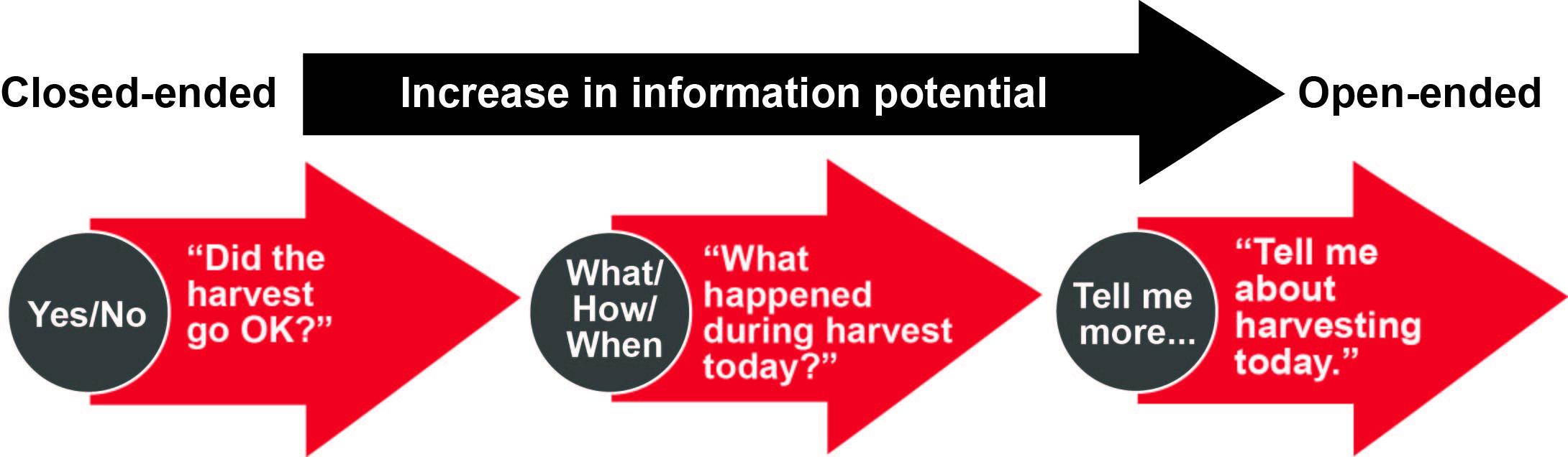

Creating Possibilities through Open-Ended Questions

One of the most effective ways to gather information is by using open-ended questions (Figure 7). An open-ended question requires more than a “yes” or “no” answer. Maximizing your use of open-ended questions can give you a robust understanding of your team, your land, and the state of your operation while increasing your problem-solving potential. Additionally, using more open-ended questions sends the message that you are considering your team in your decisions, which can help build and maintain trust.

If you are a leader in an agricultural operation, collecting as much information as possible about your operations is key to your success. Open-ended questions help you better understand the root of issues that arise on your farm. They also help to minimize assumptions and misunderstandings. When you find yourself upset, remaining curious about the topic at hand may open the door to novel solutions to a problem. We may even realize what we thought was happening wasn't something to worry about at all. Remaining curious is a powerful tool that can help us avert many future conflicts on our operations.

More Complex Situations

The examples above use specific conflicts that have recently arisen between two people. Managing conflicts becomes more difficult when the individuals involved have a long history of unresolved conflicts, when more people are involved, or when a negative workplace culture has become entrenched over time. These kinds of situations will not be resolved in a single conversation, but the specific communication skills presented above will help reduce tensions while you work to resolve complex, entrenched conflicts.

Additionally, farm leaders can prevent and manage difficult conflicts by 1) proactively working to create a positive workplace culture, 2) creating a documentable process for addressing concerning employee performance and misconduct, and 3) learning about your responsibility as an employer or supervisor to prevent harassment in the workplace.

- A positive workplace culture: You can turn peer pressure into a positive tool by collaboratively engaging your team in identifying what positive team norms you all want in your workplace. Example exercises for doing this are available online, such as this two-page guide from Penn Medicine: https://bit.ly/worknorms

- Addressing concerning employee performance and misconduct: Having a clear, consistent policy for responding to concerning employee behavior or misconduct can help you take some of the personal emotional stakes out of the situation. Instead of reacting in the moment, it gives you a process to follow that you decided on in the past when you were in a more calm state. Although policies for addressing employee conduct are often called “disciplinary policies,” these processes are not about punishment, but instead about identifying and improving behaviors. As best practices, conflict resolution strategies should be part of this process; there should be space for listening to the employee’s concerns or grievances; the process should be clear to employees and can be provided in writing in an employee handbook; and each step of the process should be documented in writing (Cosentino n.d.). Example disciplinary policies are available, but you will need to tailor your policy to your specific scale and operation, and you should ideally consult a lawyer (Kuligowski n.d.). For a comprehensive guide to address employee performance issues, refer to the U.S. Office of Personnel Management guide: https://bit.ly/3svI3Rd

- Prevent harassment in the workplace: Some behaviors move beyond the realm of interpersonal conflict into the realm of unlawful harassment. Farm leaders have an important legal responsibility to prevent employees from being harassed, both by supervisors and by coworkers. Anti-sexual harassment training toolkits specifically for agricultural employers are available from Cornell University (https://bit.ly/3QxC9H5) and the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center (https://bit.ly/3shECh7). Information on other kinds of unlawful harassment, employee rights, and employer responsibilities are available from the U.S. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission.

Wrap-Up

In this fact sheet, you learned to recognize how you and your team use different conflict-handling modes. You learned strategies for communicating clearly through a conflict. These communication techniques can benefit everyone and improve farm operations. Speaking in a new way may feel awkward at first, but with time you will become more comfortable using techniques like reflective listening and distancing phrases. Try modeling these techniques to your team and seeing if they spread. As you move forward:

- Consider spending the time to figure out what topics escalate you. This can leave you better prepared to process and manage your emotions at the moment the topics arise.

- Spend some time discovering ways to put your values into words.

- Use your next conversation as a place to practice non-judgment, staying curious, using open-ended questions, and reflecting on feelings, topics, and values.

Consider proactively putting systems in place to prevent and prepare for conflicts, such as collaboratively identifying workplace norms, and developing an employee handbook with processes for employees to express their concerns and for supervisors to address employee performance issues.

Additional Resources

Crisis Response Resources

If you need immediate help with a crisis, look for options on this list of resources. https://go.umd.edu/46XkJuu

If you are a farmer in crisis or know of someone in need of immediate assistance, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline dial 9-8-8, or dial 9-1-1, or call Farm Aid at 1-800-327-6243.

Maryland Agricultural Conflict Resolution Service

Some conflicts may benefit from a neutral third party, such as a mediator. The Maryland Agricultural Conflict Resolution Service is the official US Department of Agriculture (USDA)-certified agricultural mediation program for Maryland, offering confidential assistance to help resolve agriculture-related issues in a productive environment. https://mda.maryland.gov/Pages/acrs.aspx

United States Equal Opportunity Employment Commission

“The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is responsible for enforcing federal laws that make it illegal to discriminate against a job applicant or an employee because of the person's race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy and related conditions, gender identity, and sexual orientation), national origin, age (40 or older), disability or genetic information. Most employers with at least 15 employees are covered by EEOC laws (20 employees in age discrimination cases). Most labor unions and employment agencies are also covered.”

- Employer responsibilities related to harassment: https://bit.ly/3FQlutw

- National Agricultural Law Center guide to equal employment regulations that apply to agricultural workers: https://bit.ly/40ztOas

Conflict Styles, Outcomes, and Handling Strategies

This article from Penn State Extension describes conflict styles and outcomes while providing strategies for addressing conflict. https://extension.psu.edu/conflict-styles-outcomes-and-handling-strategies

Farm Stress Management

Emotional self-regulation helps keep us from escalating conflict unnecessarily. This resource list from UMD Extension provides a good foundation for understanding Stress Management while giving us plenty of resources to help grow our capacity for resilience. https://go.umd.edu/40memyo

Inclusive mediation

For a Maryland-grown approach to mediating community conflicts, read this guide to inclusive community mediation.

Harmon‐Darrow, C., Charkoudian, L., Ford, T., Ennis, M., & Bridgeford, E. (2020). Defining inclusive mediation: Theory, practice, and research. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 37(4), 305-324. https://bit.ly/inclusivemediation

The SAGE Handbook of Conflict Communication

If you would like to dig into the research on and theories of conflict management, the SAGE Handbook of Conflict Communication is a comprehensive resource.

Oetzel, J. G., & Ting-Toomey, S. (Eds.). (2006). The SAGE Handbook of Conflict Communication: Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976176

References

- Bennett, M. (2023, April 4). Conflict management styles explained in 5 minutes. Niagara Institute. Retrieved May 1, 2023, from https://www.niagarainstitute.com/blog/conflict-management-styles/

- Cosentino, J. (n.d.) Disciplinary Action at Work: All HR Needs to Know. Academy to Innovate Human Resources. Retrieved Nov. 8, 2023 from https://www.aihr.com/blog/disciplinary-action/

- Crisis Prevention Institute. (2022, June 28). CPI’s Top 10 De-escalation Tips Revisited. Retrieved Nov. 10, 2023 from https://www.crisisprevention.com/Blog/CPI-s-Top-10-De-Escalation-Tips-Revisited

- Kuligowski, K. (n.d.) How to Develop a Disciplinary Action Policy. Business News Daily. Retrieved Nov. 8, 2023 from https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/15896-disciplinary-action-policy-how-to.html

- Penn Medicine (n.d.) Guide to Developing Team Norms. Retrieved Nov. 8, 2023 from https://www.med.upenn.edu/uphscovid19education/assets/user-content/documents/leading/guide-to-establishing-team-norms-final.pdf

- Thomas, K. W., & Kilmann, R. H. (2007, May 1). Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument – Sample Profile and Interpretive Report. lig360.com. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://lig360.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Conflict-Styles-Assessment.pdf

- Thomas, K.W., and Kilmann, R. H. (1978). Comparison of four instruments measuring conflict behavior. Psychological Reports 42:1139-1145.

- U.S. Office of Personnel Management. (2017, March). Addressing and Resolving Poor Performance: A Guide for Supervisors. Retrieved Nov. 9, 2023 from https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/employee-relations/employee-rights-appeals/performance-based-actions/toolkit.pdf

TAYLOR KINNIBURGH

Intern, University of Maryland Extension, Baltimore City Office

NEITH LITTLE

Extension Agent, University of Maryland Extension, Baltimore City Office

nglittle@umd.edu

All figures adapted from “Community Mediation Maryland” workshop taught by Taylor Kinniburgh at Future Harvest Conference, 2020 unless otherwise noted.

This publication, Leadership and Conflict on the Farm (FS-2023-0671) is a part of a collection produced by the University of Maryland Extension within the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

The information presented has met UME peer-review standards, including internal and external technical review. For help accessing this or any UME publication contact: itaccessibility@umd.edu

For more information on this and other topics, visit the University of Maryland Extension website at extension.umd.edu

University programs, activities, and facilities are available to all without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, marital status, age, national origin, political affiliation, physical or mental disability, religion, protected veteran status, genetic information, personal appearance, or any other legally protected class.

When citing this publication, please use the suggested format below:

Kinniburgh, T & Little, N. (2023). Leadership and Conflict on the Farm (FS-2023-0671) University of Maryland Extension. go.umd.edu/FS-2023-0671.