EB-418 | May 2014

State Review of Environmental Impacts Could Result in Mineral Leasing Opportunities in Maryland

Starting in 2007, many western Maryland landowners saw increased oil and gas leasing as gas companies further developed the Marcellus Shale which contains one of the largest known natural gas reserves in the world. The Marcellus Shale is adjacent to a large energy market in the East Coast. The formation is located primarily in eight states, including Pennsylvania, New York, West Virginia, and western Maryland. Many landowners may think that the period for understanding how to negotiate an oil and gas lease has passed, but Maryland’s oil and natural gas resources have not been fully developed.

There may be additional opportunities for mineral owners in Maryland to lease their oil and gas mineral rights. Currently, the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) has completed a review of other states’ best management practices to determine if gas production can occur in the Marcellus Shale with limited impact on other Maryland resources (Eshleman & Elmore, 2013). This review was completed by two faculty members at the University of Maryland’s Center for Environmental Science and presents proposed best management practices that could be adopted in Maryland. MDE is now reviewing this report to determine which practices to implement.

When the review in August of 2014 is completed and the industry sees a rebound in natural gas prices, oil and gas companies again may offer Maryland mineral owners the opportunity to sign leases. Understanding the parts and terms of an oil and gas lease can help mineral owners negotiate leases that will effectively protect their interests and limit disputes. In all cases, mineral owners should work with an attorney well-versed in gas and oil law to protect their rights.

There are few Maryland court decisions involving the interpretation of leases. Maryland also has limited regulation of the oil and gas industry compared with neighboring states, such as Pennsylvania and West Virginia. This disparity could change when the MDE completes their review before allowing development of the state’s portion of the Marcellus Shale formation. Parties to an oil and gas lease should carefully craft lease agreements that remove some uncertainties and not rely on the courts to eventually decide in one party’s favor.

Note: This publication is intended to provide general information about legal issues in oil and gas leasing and should not be construed as providing legal advice. It should not be cited or relied upon as legal authority. State laws vary and no attempt is made to discuss laws of states other than Maryland. For advice about how the issues discussed here might apply to your individual situation, you should consult an attorney.

Who Owns the Minerals?

In Maryland, a real property owner is assumed to own “from the heavens to the center of the earth.” Real property includes two separate, severable estates: 1) the surface estate and 2) the mineral interest. A real property owner can own either one or both estates. The surface estate is the right to use the surface and all substances below it that are not defined as minerals.

The mineral estate is the ownership rights in minerals found in real property. Minerals, such as oil, natural gas, coal, iron, gold, etc., are considered any organic or inorganic substances that have value, based on their physical properties. Some things found on or in the surface estate of real property are not considered minerals, such as gravel, sand, and subsurface water, which do not possess exceptional qualities or value. What is considered a part of the mineral estate will depend heavily on the language used when the two estates are severed.

The mineral and surface estates can be severed from one another resulting in different owners for the two estates. One piece of property, therefore, can have different owners for the mineral and surface estates. When the two estates are separated, the mineral estate owner of might retain some rights to use the surface estate to develop the mineral estate. In Maryland, this mineral reservation creates a perpetual estate.

The Court of Appeals in Maryland has found that in certain cases, the reservation of the mineral estate may carry an implied easement to use the surface estate. When the minerals are reserved, the mineral estate owner may not know the potential uses by the surface estate holder which could conflict the implied easement. Because a court could be unwilling to find an implied easement to use the surface, the mineral estate holder would want to consider reserving a right to utilize a portion of the surface in the deed separating the two estates.

For example, Digger Barnes sells the surface Blackacre to J.R. Ewing, but Digger retains the mineral estate in Blackacre. Digger used Blackacre primarily for agriculture, but J.R. intended to build a housing development on the property. Digger knew of J.R.’s intended use of Blackacre at the time of the sale.

Digger would not retain an implied easement to use the surface of Blackacre to develop Digger’s mineral estate (Snider, 2003).ᶦ Digger would want to consider retaining an easement to utilize a portion of the surface to develop the mineral estate.

The Maryland Court of Appeals, in the Snider case, determined that the owner has a right to be free from “unreasonable interference” from mining operations. The facts in each situation will determine what is considered unreasonable. Typically the mineral estate owner is allowed to use the surface to the extent reasonably necessary to develop the mineral estate; this is measured by the customary practices in the industry.

In an oil and gas situation, the mineral owner will be able to put up a drilling rig, tanks, and build roads necessary to develop the mineral estate. The courts ruled that seismic equipment constitutes a reasonable use of the surface. Building more roads than necessary has been ruled an unreasonable use. For example, Digger owns only the surface estate of Blackacre and Oil Company constructs a road across the property from the main road to the well. The company also constructs roads that Digger did not request and that are not necessary for oil and gas operation. What happens when an oil and gas company wants to drill a well that will severely impact the surface owner’s current use? Some states have adopted the “accommodation doctrine” to help settle disputes between the two uses. The accommodation doctrine requires that the surface owner’s existing use would be impaired or disrupted by the oil and gas operations and that there are less disruptive alternatives available that meet established oil and gas industry mineral extraction practices. As of April 2014, the Maryland Courts have not officially adopted the accommodation doctrine.

For example, Charlie produces corn on Blackacre using a center-pivot irrigation system which can clear obstacles less than seven feet high. Gas Company has developed a natural gas well in the middle of Blackacre and the equipment necessary to extract the natural gas will be 17 feet high. If a viable alternative technology that is under 7 feet, exists then Gas Company could be forced to adopt the alternative technology to accommodate Charlie’s center-pivot irrigation system.

Maryland Legislature Passed Dormant Mineral Law

A dormant mineral law reunites the surface and mineral estates if the latter has not been used for a certain period of time. The Dormant Mineral Interests Act (Act) is found in Maryland Environment Code Sections 15- 1201 through 15-1206 (2012). The Act only applies to unused mineral interests severed from the surface estate and not to mineral interests owned by the surface owner (Section 15-1203).

Mineral interests are considered in use when there are:

- active mineral operations on or below the surface;

- payment of taxes related to the mineral interest;

- certain legal instruments recorded;

- or a deed, judgment, or judicial decree recorded judgment or decree that makes reference to the mineral interest (Section 15-1203(c)(1)(i)-(iv)).

The use of an injection well, disposal, or storage in the mineral interest does not constitute use according to the Act (Section 15-1203(c)(2)).

A mineral owner who has not used his/her interest for at least 20 years should contact an attorney to help file the proper notice to preserve their interest. The notice of intent to preserve must be filed in the county where the mineral interest is located. The notice of intent to preserve must include the mineral owner’s name, a legal description of the mineral interest, and the deed, judgment or judicial decree that created the mineral interest. If the mineral interest has been unused for at least 20 years and the owner has not filed a notice of intent to preserve it, the surface owner can file to terminate the dormant mineral interest in the circuit court where the mineral interest is located. The resulting judgment is similar to a quiet title action. In this instance, a surface owner is filing a lawsuit with a circuit court seeking a court order that prevents the dormant mineral estate owner from claiming that he/she retains an interest in the mineral estate.

For example, Digger Barnes owns a surface estate in which the mineral estate of a long-defunct company was severed in the 1840s. To Digger’s knowledge, no one has used the mineral estate in the past 50 years. Digger could contact an attorney and file a quiet title action to remove any rights the defunct company could have in the mineral estate.

Oil and Gas Leases are Conveyances and Contracts

Oil and gas leases state the terms and conditions of voluntary transfers of interests in real property that make mineral estates profitable through exploration, development, and production of the property’s oil and gas resources. In this section,the mineral owner(s) will be referred to as the lessor(s) and the oil and gas company as the lessee. The lease will on exploration, development, and production of oil and gas resources.

The oil and gas lease is an important document which could govern the relationships between lessor and lessee for many years. Before signing any lease, the mineral owner should discuss the lease with an attorney competent in oil and gas issues in Maryland in order to

- have all terms of the lease fully explained;

- reduce possible costly litigation in the future; and

- determine any necessary additional language more favorable to a mineral owner.

Oil and gas leases can come in two varieties:

- A delay rental lease requires yearly rental payments to be made to the lessor by a set date. The yearly rental payments will continue until drilling operations are conducted on the leased minerals or the lease expires.

- A paid-up lease does not require yearly rental payments, but only one rental payment made at the start of the lease.

In negotiating an oil and gas lease, the lessor will receive a bonus per-net-mineral-acre payment for leasing the mineral rights. A lessor might have to take a smaller bonus payment in exchange for maximizing favorable clauses such as a greater royalty share or better terms related to possible surface damage. Negotiating a gas and oil lease will depend on each lessor’s goals and other considerations.

An oil and gas lease can contain any provisions that the two parties agree on, but as well as some clauses common to in most oil and gas leases. Oil and gas leases also may contain some implied covenants based on state law.

Courts in Other States have been Willing to Imply Certain Lease Covenants, Even if Parties Did Not Include Them in Written Lease

Implied covenants create obligations that an oil and gas company must fulfill. The company will be judged against a reasonable prudent operator standard in meeting these obligations. The standard looks to how other operators would have acted in the same situation and is very fact-specific.

The implied covenants are to:

- explore the leased mineral estate;

- reasonably develop the leased mineral estate;

- protect against drainage from nearby wells; and

- market the oil or gas

The implied covenant to explore means that an oil and gas company will use reasonable diligence to determine the presence of oil and gas on the leased property through sufficient means, such as sinking an exploratory well. Early in the history of oil and gas, this implied covenant was necessary so lessees would not delay exploration on leased property until favorable market conditions. Today, this implied duty is typically dealt with by delaying rental payments until the oil and gas company is ready to drill a well.

Once oil and/or gas have been discovered, the company will need to reasonably develop the leased mineral estate. Under the terms of this covenant, the oil and gas company will put the proper number of wells on the leased property necessary to reasonably develop and extract the minerals. In determining if the implied covenant has been breached, the courts consider many factors, including geological data, size of the leased property, the number and location of wells in the area of the leased property, existing wells productive capacity, and how long after the last well was completed were additional wells demanded (Hall, 2010).

Unlike most other below-ground mineral resources oil and gas can move under the surface. Producing wells near the leased property can drain oil and gas from the leased property and rob the mineral owners of royalties. The oil and gas company has an implied duty to protect against drainage from nearby wells. Drainage in shale gas typically depends on the way the well was drilled--horizontal or vertical--and the extent of the fracture development used (American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 2011).

The typical ways to protect against drainage are to drill an offset well, when profitable, or by unitizing or pooling the surrounding leased properties (Hall, 2010). Pooling and unitization enable combining leased property under common management and allow for efficient development of oil and gas resources.

Some courts have determined that the oil and gas company may have an implied duty to market the oil and/or gas once discovered. In order to fulfill this implied covenant, an oil and gas company would need to exercise reasonable diligence in marketing the minerals after pipelines are laid to the well site.

These basic implied covenants and others exist in other states, such as an implied covenant to further explore unknown producing formations. Each of the above implied covenants has been recognized in other states by either statute or a court decision, but not in Maryland. However, parties in Maryland still may want to draft leases that include the implied covenants.

Oil and Gas Granting Clause is Typically First in Lease

The granting clause in a lease states the extent of the interest being leased, including describing the property, its size (acres), and the type of minerals. The granting clause can also limit formations the oil and gas company will be allowed to explore. For example, the mineral owner could grant the oil and gas company only the right to explore the Marcellus Shale formation and no others that the lessor may own. The lessor should carefully determine d how much of his/her interest to lease and consider negotiating separate leases for each tract of land or formation.

Habendum Clause States the Duration of the Lease

A lease, for example, could that it “shall remain in force for a term of five (5) years and as long thereafter as oil or gas, or either of them, is produced from said land by the lessee in paying quantities.” This particular clause states two different terms when the lease could expire--a fixed term (5 years) and an unknown amount of time in the future based on certain conditions.

The fixed timeframe of a lease is known as the primary term. During the primary term, a lessee has the right to explore and drill for oil and gas. If the lessee does not exercise this right during the primary term, the lease will expire. The length of the primary term can be modified by other terms in the lease; either shortened or lengthened based on certain situations.

The secondary term of the lease is the period of time that oil and/or gas is produced on the property. From our example, the secondary term would be stated “as long thereafter as oil or gas, or either of them, is produced from said land by the lessee in paying quantities.” The language in this term varies in leases, but once the lessee has a producing well, the lease enter the secondary term. The lease continues until oil and/or gas production in paying quantities has ceased on the property.

Option Clause Provides for Extension of Lease

An option clause allows a lessee to extend a lease, under conditions specified in the lease. The lessee may be required to send notice to the lessor by a certain date and to pay consideration (something of value, such as money). For example, the lease could state that

Lessee may extend the primary term for one additional period equal to the primary term by paying to Lessor, at any time within the primary term, a proportionate to Lessor’s percentage of ownership an Extension Payment equal in amount to the annual Delay Rental or by drilling a well not capable of commercial production.

With this language, the lessee would be able to extend the lease by paying a delay rental payment or by drilling a well that is not capable of commercial production.

Leases in areas where bonus payments are increasing are more likely to contain option clauses which allow lessees to lock in lower acreage rates. Leases in areas of high activity may also include an option clause if operators do not have time to drill the subject acreage within the primary term of the lease. Lessors should pay careful attention to this clause and try to have it removed if they believe lease prices will increase or they want to be able to include more favorable terms at a later date.

Depth Clause Protects Lessor When Other Formations Found at Different Depths

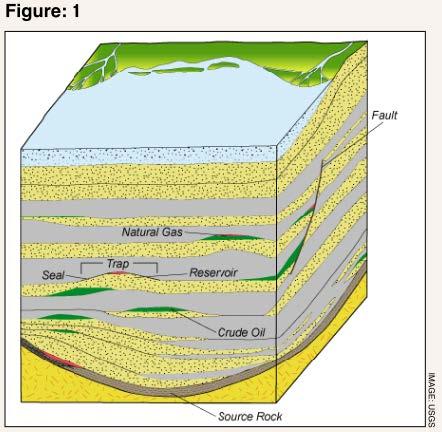

Oil and gas reservoirs are found in formations at various depths. For example, Digger may have a reservoir of natural gas in one formation and crude oil at greater depth in another formation (figure 1). If Ewing Oil is only aware of the natural gas formation, the company will drill a well and produce natural gas to hold the lease. If the crude oil formation is later discovered, would Ewing Oil be able to drill a well to that new formation without a new lease?

The lessee could drill a well to the new formation without a new lease if the original lease did not include a depth clause. A typical depth clause would state that

In the event this lease is extended by commercial production past the primary term, then on the last day of the primary term, this lease shall terminate all rights 100 feet and more below the deepest penetrated formation in the well on the leased property or in a pooled unit.

From our previous example, if Digger had included a depth clause, Ewing Oil would be required to get a new lease before attempting to produce the new formation. Digger could also sign a lease with a different lessee to produce the new formation.

Royalty Clause States Amount Lessor will be Paid When Oil and/or Gas are Produced on Leased Property

To calculate the royalty, a lessor needs to look at the lease language. If the royalty clause states “at the well” or “at the mouth of the well,” the oil or gas will be valued at the wellhead. Language such as “in the pipeline” and “at the place of sale” means that the oil or gas will be valued at those locations to determine the royalty payment.

In many oil and gas states, the issue of the types of expenses that can be deducted from the royalty has been heavily litigated. The expenses allowed depend on the language used in the royalty clause. Lessees, for example, typically cannot deduct production expenses, such as pumping costs from royalty payments. Deductible postproduction costs vary among states based on the language used in the lease, implied covenants, and custom and usage of the industry. Post-production expenses include transportation and other costs associated with marketing gas and oil.

Language such as “the gross proceeds received for the gas or oil sold, used off the premises or in the manufacture of products” typically exclude the lessee from deducting post-production costs from the royalty payment to the lessor. Language such as “deliver to a pipeline free of costs” also denotes that post-production costs cannot be deducted.

Some states, however, have allowed post-production costs deductions when they enhance the value of an already marketable product (Mittelstaedt,1998). These enhancement costs would include expenses associated with transporting already-marketable gas to the point of purchase or costs to remove water from the natural gas, also known as “dehydrating gas.” The lessee must show that post-production enhancement costs are necessary.

As of April 2014, Maryland had no statutes or court decisions determining the post-production costs that can be deducted from the royalty payment. The mineral owner should work with a competent oil and gas attorney to negotiate a royalty clause that specifies the costs that can be deducted.

Shut-in Royalty Clause Provides Payment if No Market for Well

During the life of the lease, a lessee may be forced to shut a well down because no market exists for the oil and gas at the time. For example, Ewing Oil struck gas on Blackacre, but based on current conditions, it could take 6 months to connect the well to available markets. In this case, no market would exist until a pipeline is able to service the Blackacre well. If the well remains out of production too long, the lease may be considered expired or the lessee may be in breach of the implied covenant to market the well’s oil.

A shut-in royalty clause is one way the lessee can preserve the lease during periods when the well is not active. A shut-in royalty clause will provide the lessor with a set payment in lieu of royalties. The shut-in royalty clause can limit how long a lease can be maintained with only a shut-in royalty payment.

Pooling Clause Allows Combining Leases in to Common Unit for Drilling Well

An example lease clause could state:

Lessee, at its option, is hereby given the right and power to pool or combine the acreage covered by this lease, or any portion thereof as to oil and gas, or either of them, with other land, lease or leases in the immediate vicinity thereof to the extent, hereinafter stipulated, when in Lessee’s judgment it is necessary or advisable to do so in order to properly develop and operate said leased premises in compliance with any spacing rules set by the state, or other lawful authority, or when to do so would, in the judgment of Lessee, promote the conservation of oil and gas from said premises.

A pooling clause is one way to allow voluntary pooling of gas and oil leases. If a lease does not contain a pooling clause, then lessors would have to consent before their mineral interests before they can voluntarily pooled. The lessors in the combined pool will share revenues but, because there would be more acreage under one well and more mineral owners, royalty payments would be reduced.

Some states allow for compulsory or statutory pooling. Compulsory pooling is permitted when certain statutory conditions are met for creating a common pool. Lessors can do little to avoid compulsory pooling because it will apply to any mineral owner in the proposed pool if the statutory conditions are met. As of April 2014, Maryland has no statute allowing for compulsory pooling, but mineral owners should monitor any proposed changes by the Maryland legislature or MDE.

Pugh Clause Requires Release of All Unpooled Acreage When Primary Term of Lease Expires

A lessee may decide to pool only a portion of a lessor’s mineral interest. However, it may not be clear if the producing well on the pooled portion of the mineral interest is enough to keep the lease in effect. Courts in some states have found that a producing well on the pooled mineral interest keeps the lease effective on the unpooled portions. A Maryland court has not ruled on this issue.

A Pugh clause, named after the original drafter of the clause, would require the release of all unpooled acreage (or outside the spacing unit) once the primary term of the lease has expired. Although there is no common Pugh clause, an example could state:

If at the end of the primary term, a part but not all of the land covered by this lease, on a surface acreage basis, is not included within a unit or units in accordance with the other provisions hereof, this lease shall terminate as to such part, or parts, of the land lying outside such unit or units, unless this lease is perpetuated as to such land outside such unit or units by operations conducted thereon or by the production of oil, gas or other minerals, or by such operations and such production in accordance with the provisions hereof.

The clause would allow the lease to expire on any acreage that is unpooled and does not have a producing well. For example, Digger has leased 100 acres of minerals to Ewing Oil with a 3- year primary term and the lease contains a Pugh clause. Ewing Oil has pooled 50 acres of Digger’s minerals with other mineral interests and has drilled a producing well on the pooled unit.

Ewing has not completed a producing well on Digger’s unpooled mineral acreage before the end of the 3-year primary term. At the end of primary term, Digger’s lease on the unpooled 50 acres would expire and Digger would be free to lease those acres again. The clause would not be in effect if Ewing had completed a producing well on the unpooled 50 acres.

Surface Damage Clause Protects Lessee’s Right to Reasonably Use Surface without Paying for Damages

A surface damage clause requires the lessee to pay damages for destruction to the surface used by lessee. This clause should be considered when the same party owns the surface and mineral estate to ensure that the lessee pays for any damage caused by the oil and gas operations.

Issues will develop when the mineral and surface estates have been split. Provisions of a lease will only be enforceable by the parties to the lease; in this case, the mineral owner and the oil and gas company. A surface owner may gain a right to enforce lease provisions when a court can see that the parties to the lease intended to create legally enforceable rights for the surface owner. A mineral owner may want to discuss with an attorney ways to create enforceable rights for a surface owner with any surface damage clause included in the lease.

Maryland, unlike other states such as Pennsylvania, Montana, and Oklahoma, does not have a special statutory provision that requires oil and gas companies to pay for surface damages caused by oil and gas operations. However, oil and gas companies in Maryland still may be willing enter into surface use agreements that stipulate the company’s responsibility for stated damages and may specify the amount or formula for determining compensation to the surface owner when damage occurs.

Surface damage clauses can vary among leases and can be tailored to meet the parties’ needs. The clause, for example, may require a set lump sum for each surface well site and/or stipulate payment for all surface damages to growing crops, pastureland, or other surface features, such as water bodies, drainage areas, and fences. Both parties to a surface damage clause may want to include nonjudicial ways of determining compensation when the parties cannot agree, such as selecting of appraisers or mediators to determine the value.

Lessors should assess their current uses for the surface and engage an attorney to include language in the lease to protect these uses. An oil and gas operation, for example, will build pipelines and access roads. The lessor would want to include language in the lease to require all pipelines to be buried to a certain depth, which for agricultural purposes is usually below plow depth. If the land has fences that need to be removed to construct roads or lay pipelines, the lessor should ask that those fences be reconstructed to a certain standard. If the surface is used for livestock grazing, the lessor may want to add language requiring the lessee to construct fences to keep livestock out of the lessee’s equipment. The surface owner should always remember to take photos before the operation begins and throughout the process. The photos will serve as a record of events and the original condition of the surface and to what extent operations have hampered surface uses.

Warranty Clause Protects Lessees Against Ownership Claims

The lessee will do an extensive title search to determine the true extent of lessor’s mineral interest. A lessor should consider limiting the extent of the warranty clause. The clause can be general or special warranty.

A general warranty clause requires the lessor to warranty the entire chain of title. In other words, the lessor will insure a clear property title back to the first owner; in Maryland this could mean warranting transactions going back over 400 years.

Consider the following example. J.R. Ewing leases a 50-acre mineral interest in Blackacre to West Star based on documentation presented by J.R. proving his ownership. J.R.’s lease includes a warranty clause. Once the well is drilled and producing gas, Digger Barnes produces documentation showing that he owns the 50 acres of minerals. Under the warranty clause, West Star could require J.R. to defend any adverse claims of title, like Digger’s claim of ownership, which could impact the company’s leased interest.

A special warranty clause would protect the lessee only from defects caused by the lessor and not anyone else in the chain of title. West Star could only require J.R. to defend adverse claims of title if they happened while J.R. owned the land. If Digger’s adverse claim arises out of an exchange between Digger and the previous owner, then West Star would have to defend against Digger’s claims. Again, a lessor should consult an experienced oil and gas attorney to discuss ways to limit a warranty clause.

An Assignment Clause Can Limit or Allow the Transfer of Rights to a Third Party

The oil and gas industry has a long history of using assignment of leases. Speculators may move in, lease large mineral tracts with no intention of drilling a well. Rather, the speculators plan to sell the leases at higher prices to oil and gas companies looking to drill in the area. Oil and gas companies may assign leases in order to gain financing for other projects. Typically, it’s in the lessee’s favor to retain the right to assign the lease.

Lessors also benefit from allowing assignment because it can ensure that the minerals are developed in a timely manner. An experienced oil and gas attorney can provide help with ways to protect the lessor in cases of assignment by the lessee. To gain some control, for instance, the lessor may want to add assignment clause language that requires the lessee to notify the lessor of a lease assignment within a certain number of days. Language that does not release the original lessee from liability for a default on any of the assigned portions of the lease will also benefit the lessor.

For example, Ewing Oil has a lease with Digger on 100 acres with a producing gas well. Ewing Oil needs quick capital for another project and assigns 50 acres of Digger’s lease to West Star Oil, and West Star defaults on the royalty payments owed to Digger. Digger’s lease contained an assignment clause that did not release Ewing Oil from a royalty payment default. Digger would be able to seek payment from Ewing Oil and West Star for the defaulted royalty payments.

Free Water Clause

Drilling an oil or gas well requires an estimated 5 million gallons of water to horizontally drill and hydraulic fracture a well (Chesapeake Energy, 2012). Unless specified otherwise in the lease, many states allow a lessee use of above- or below-ground water.

Maryland currently has no rule allowing lessees free access to water on the property so a lessor may want to consider limiting the lessee’s access. An attorney, for example, may suggested adding a free water clause stipulating that the lessee obtain the lessor’s permission before using water. The lessor may also require the lessee to pay for any water used in drilling and hydraulic fracturing operations.

Force Majeure Clause is Used to Excuse Nonperformance When it is Out of the Parties’ Control

The Force Majeure clause is also known as an “Act of God” clause. , The clause is triggered when an event is unexpected and prevents performance. For example, Ewing Oil is drilling a well in Maryland and is experiencing permit delays through the Maryland Department of the Environment. Ewing Oil finally receives its permit one month after the primary term of their leases expires.

Traditionally, a Force Majeure clause would not apply in this case because it is assumed oil and gas companies understand that delays typically happen when dealing with a permitting process. The courts traditionally have applied Force Majeure clauses strictly; every condition triggering the clause must be met. For this reason, the clauses are rarely enforced by the courts. A lessor presented with a Force Majeure clause in a lease would want to discuss the clause with an attorney to consider the appropriate difficulties that will be acceptable.

Surface Restoration Clause is Uncommon but Could Benefit Lessor

An oil and gas lease will eventually end, the well will run dry and pumping equipment, pipelines, concrete pads, and other equipment will no longer be needed. A surface restoration clause should include the necessary conditions for production to be considered completed, such as the length of time a lessee can go without producing oil or gas. Lessors can avoid costly litigation by stipulating the terms in advance under which production is considered complete. The surface restoration clause should specify the conditions and requirements for restoring the surface to its previous condition.

State of Maryland Review Could Affect Oil and Gas Leases

Mineral owners should closely monitor the State’s review and the resulting potential legislation and regulations. With many oil and gas companies withdrawing their permit applications from MDE, it is unclear if these companies will exercise their options to extend current leases past the expiration of their primary terms. If not, mineral owners could have a second opportunity to lease their mineral rights to new companies. Owners should always consult an attorney to develop language for the lease that benefits and protects their rights and concerns.

References and Endnotes

- 38 Am. Jur. 2d Gas & Oil § 59 (2013).

- 38 Am. Jur. 2d Gas & Oil § 110 (2013).

- American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Shale Gases (April 9, 2011). Available at http://emd.aapg.org/technical_areas/gas_shales/index.cfm.

- Anderson, O. L., Calculating Royalty: “Costs” Subsequent to Production—“Figures don’t lie, but . . .”, 33 Washburn L.J. 591 (1993-94).

- Calvert Joint Venture No. 140 v. Snider, 816 A.2d 854 (Md. 2003).

- Chesapeake Energy, Water Use in Deep Shale Gas Exploration, Fact Sheet (May 2012). Available at http://www.chk.com/media/educational-library/fact-sheets/ corporate/water_use_fact_sheet.pdf.

- Eshleman, Keith N. and Andrew Elmore, Recommending Best Management Practices For Marcellus Shale Gas Development in Maryland, Maryland Department of Environment (Feb. 18, 2013).

- Fambrough, Judon, Hints on Negotiating an Oil and Gas Lease, Texas A&M University Real Estate Center, Technical Report 229 (2002).

- Hall, Keith B., The Continuing Role of Implied Covenants in Developing Leased Lands, 49 Washburn L.J. 313 (2010).

- Md. Code Ann. Envir. §§ 14-101 through 14-125 (2013).

- Md. Code Ann. Envir. §§ 15-1201 through 15-1206 (2013).

- Mittelstaedt v. Santa Fe Minerals, Inc., 953 P.2d 1204 (Okla. 1998).

- McFarland, John B., Fundamentals of Negotiating Oil and Gas Leases, Paper presented at the American Agricultural Law Association’s Law Symposium, Austin, Tx. October, 2011.

ᶦOpinions of the Court of Appeals of Maryland (Maryland’s version of a state supreme court) and the Court of Special Appeals of Maryland (Maryland’s intermediate court of appeals) are available online for free at http://www.courts.state.md.us/opinions.html. The Snider opinion is available at http://mdcourts.gov/opinions/coa/2003/52a02.pdf.

LORI LYNCH

Extension Economist

llynch@umd.edu

PAUL GOERINGER

Extension Legal Specialist

lgoering@umd.edu

This publication, State Review of Environmental Impacts Could Result in Mineral Leasing Opportunities in Maryland (EB-418) is a part of a collection produced by the University of Maryland Extension within the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

The information presented has met UME peer-review standards, including internal and external technical review. For help accessing this or any UME publication contact: itaccessibility@umd.edu

For more information on this and other topics, visit the University of Maryland Extension website at extension.umd.edu

University programs, activities, and facilities are available to all without regard to race, color, sex, gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, marital status, age, national origin, political affiliation, physical or mental disability, religion, protected veteran status, genetic information, personal appearance, or any other legally protected class.