From Winter 2024 issue of Branching Out. Subscribe to Branching Out here. Read more Invasives in Your Woodland articles here. This article contains information current as of date of publication.

North America is home to a variety of berries prized for their taste, including native blueberries, blackberries, and raspberries. This issue’s spotlight falls on a shrub in the rose family that writers describe as very edible, or delicious, or amazing. Another describes them as “not a sour berry in the bunch.” This is the wineberry, and despite its tastiness, it is non-native and invasive. This Asian native was imported to the United States in 1890 by berry growers. They wanted to use it as breeding stock with native raspberries—a practice continued to this day—but it escaped from cultivation and was first observed in natural areas in the 1970s.

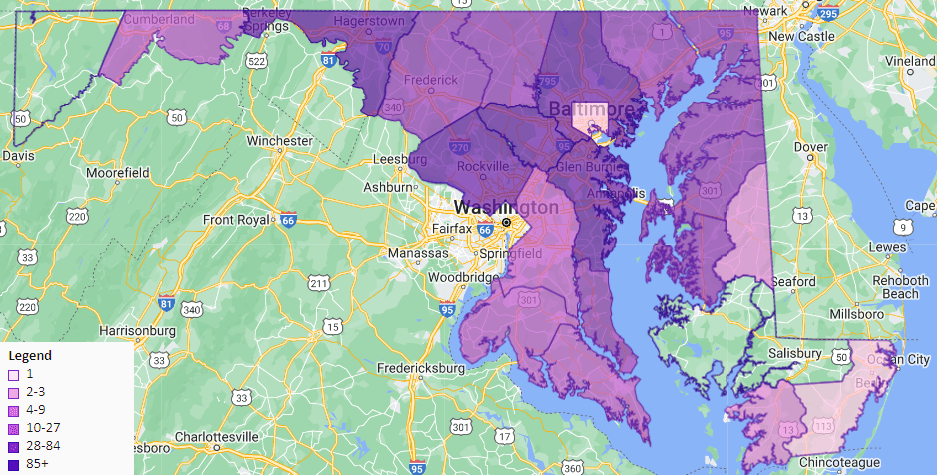

Today, it is found throughout most of the East Coast and Midwest states, and is considered invasive in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. This issue’s map from the Maryland Biodiversity Project shows its reported concentration across the state (darker shades of purple represent greater concentrations).

What is it?

Wineberry (Rubus phoenicolasius), also called “wine raspberry,” grows as arching canes that can reach nine feet in length. It forms thickets in a variety of habitats with moist soil, including woodlands, forest margins, and stream and wetland edges, where its vigorous growth can crowd out native species. It prefers open areas with abundant sunlight, but may become established in forest settings when a tree falls and opens a hole in the canopy. While wineberry’s thickets may provide cover for some wildlife, other animals cannot penetrate the dense vegetation.

Wineberry canes grow in two stages. In year one, the canes are vegetative; in year two, they become woody and produce lateral branches, flowers, and fruits. While each cane lives only two years, the plant produces new canes every year.

How does it spread?

Wineberries spread naturally when the tips of the canes reach the ground, re-rooting at the tips. It can also spread via root buds. Additionally, seeds from the fruits can be spread by birds and other animals via droppings.

How can I identify it?

Wineberry leaves are divided into three heart-shaped leaflets that are alternate on the stem and that have a whitish and waxy underside. The margins are toothed. The species is most easily identified by its mature canes, flowers, and fruit. The woody canes appear reddish from a distance, which is caused by glandular hairs along the entire length of the stem. The flowers have five petals that emerge in June. The fruits are bright red, resembling its raspberry cousins. The canes lose their leaves in winter. See the photo gallery below.

How can I control it?

The best way to control the spread of wineberry is to not plant it. As mentioned earlier, berry growers still use it as breeding stock, but under tightly-controlled conditions. If property owners find wineberry in natural areas, manage the plants as soon as possible. Removing the canes mechanically by digging can be effective as the plant does not have a vigorous underground storage system. Herbicides are also effective. Be sure to plant native species in the disturbed areas and return to ensure no wineberries re-sprout.

For more information:

Learn more about wineberry:

Wineberry (Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas)

Fact Sheet: Wineberry (Plant Conservation Alliance’s Alien Plant Working Group)

Invader of the Month: Wineberry (Maryland Invasive Species Council)